This post is Part I of several posts where we have looked at how local NGOs in the water sector work with data. The attachment has more information about the series. Part II focuses on the indigenous people who make up the Nilgiris. We will continue posting about Keystone and their experiences with managing data collection. We will also post tips for better data management.

Keystone Foundation was started in 1993. The work started with a survey of honey hunters in the hill areas of Tamil Nadu in 1994 and has now expanded to many parts of the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve including looking at various issues around water. With its focus on the development of the indigenous communities in the Nilgiris, Keystone started off with setting up a water supply system for one village in 1995. The attachment has more information about this project and Keystone.

Keystone has worked in the Sigur plateau to set up village-level water distribution systems that are being managed by user groups in those villages. Even though the Nilgiris is a water-rich district, there is a poor access to clean water in many areas.

It is also the poor monsoon (IMD estimates a 23% deficit[i] for Tamil Nadu) that caused water levels in most neighborhoods to drop. Many villages have started tapping water sources from old springs. The critical role played by these traditional water sources brings to the fore discussions on their recent disuse and pollution. In this context, Hill Water and Livelihoods : A report on Nilgiris Water Resources by the Keystone Foundation offers interesting insights into the socio-geography and cultural dimensions of these traditional water sources. This article is the first of a two-part series based on the report.

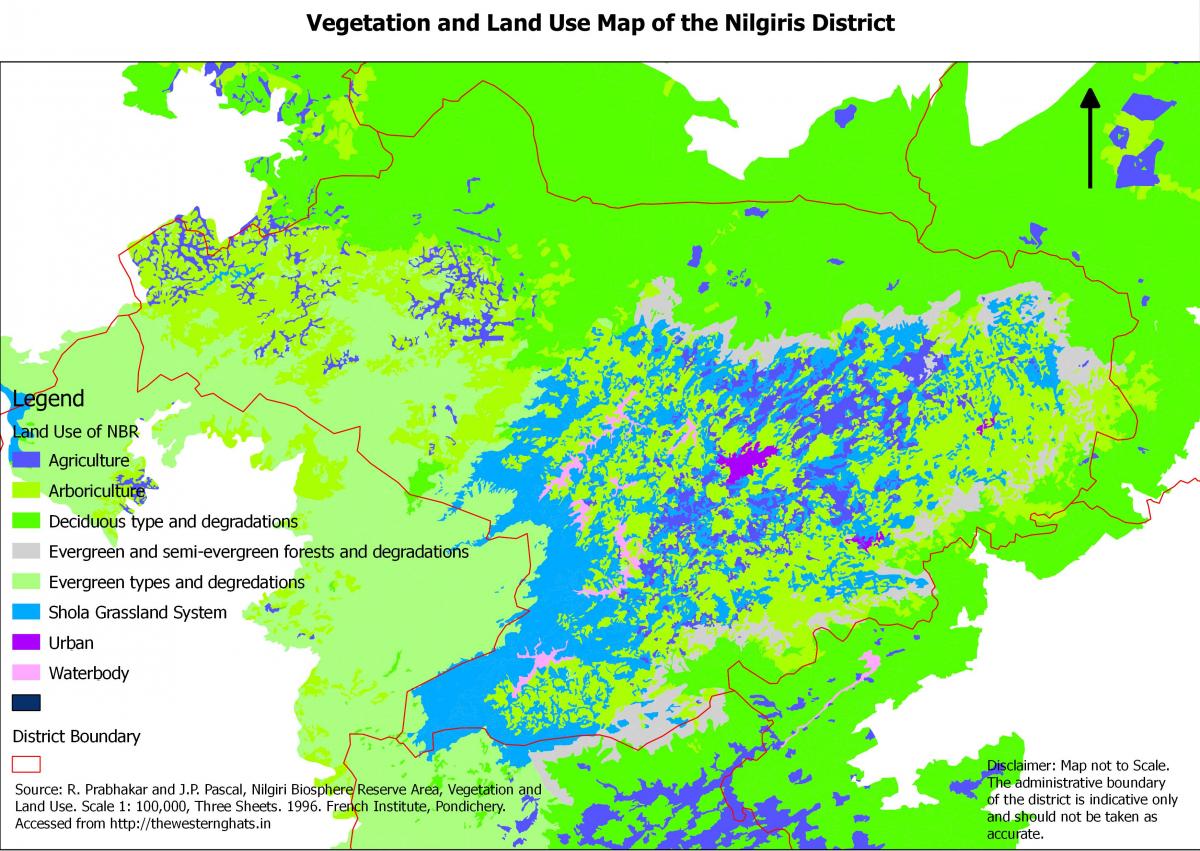

Pratim Roy, the Principal Investigator of the study and the director of Keystone, says that water forms a connecting link between the ecology and economics in the Nilgiris. The district is located at an elevation range of 1000-2636 metres above sea level, and the topography includes high peaks, undulating grasslands and a plateau region. The drainage of the district can be divided into four distinct basins – the Moyar, the Bhavani (both of which feed the Cauvery), the Chaliyar and the Kabini. Both the colonial State and the democratic government have manipulated the water flows in the district. Most of the large rivers have been tapped for power generation, and the district contributes about a third of the hydroelectric power available in the State.

To understand the local contexts of water, the Hill Water study surveyed 61 habitations across the four basins. This district is home to various indigenous people including the Kurumbas – Alu, Jenu, Mullu and Betta, Kasava, Irula, Toda, Kota, Kattunaika, Paniya, Badaga, Thoraiyya Badaga and the Mountadden Chettis. Each of these communities has favoured different elevation for their habitations. The land use at these elevations has evolved to suit the livelihood requirements of these communities. Water use then, follows these land claims. The table below summarizes the natural environment, social demography and water flows.

Elevation (meters above sea level)

|

Lower than 1000 |

1000-1800 |

Higher than 1800 |

|

|

Natural forests |

Dry deciduous and scrub |

Moist and dry deciduous |

Shola, grasslands |

|

Commercial forests |

|

|

Cinchona, eucalyptus, pine, wattle plantations |

|

Indigenous communities |

Betta Kurumbas, Irulas, Kattunaikans, Paniyas, Kasava, Mullu Kurumbas

|

Alu Kurumbas, Irulas, Betta Kurumbas

|

Todas, Kotas

|

|

Other communities |

Malayali, Tamil, Sri Lankan Tamil repatriates |

Badaga, Tamils, Sri Lankan Tamil repatriates |

Badaga, Tamils, Malayalis, Kannadigas, Sri Lankan Tamil repatriates |

|

Water Resources |

Mostly polluted water enters the Reserve Forests zone, passing through scattered tribal hamlets and large wildlife reserves. All hallas (streams) merge into the four basins through the few major rivers. The water carries massive top soil and wastes. In the monsoon, water sources are visible, but during the summer most of them are dry. The plantation sector suffers, and the reservoirs are half empty. |

Streams become rivers and pass through urban and rural settlements. It is mostly a plantation and agriculture sector. The sources of pollution in this zone are domestic waste as well as industrial and chemical waste. There are large concentrations of populations, including immigrants, natives, tribals, service sector professionals, and the business community, all of whom use waters in diverse ways. |

Water is trapped in the grasslands and sholas, releasing itself gradually through marshes and swamps. There is a network of hydroelectric projects for electrical power generation. The landscape has large reservoirs. The source of pollution in this zone is agro chemicals. |

|

Cultivated crops |

Coffee, pepper, jackfruit, silk cotton, tea, ginger, paddy (Gudalur), millets |

Tea, coffee, pepper, jackfruit, silk Cotton |

Tea and vegetables |

|

Trade and business |

Homestead produce, wage labour, tea (Gudalur), farm income |

Timber, tea, small business, wage labour, homestead produce |

Timber, tea, tourism, township |

The study notes how widespread land use changes in the catchment of streams, and the harnessing of the water itself for hydroelectricity and large scale irrigation, has resulted in the loss of control over these water resources by the local communities – while, at the same time, establishing a centralized administrative system. Many of these grasslands once formed the grazing grounds of the pastoral Toda community. The submergence of these grasslands has forced these communities to abandon their older habitations and reduce their cattle holdings.

The study notes how widespread land use changes in the catchment of streams, and the harnessing of the water itself for hydroelectricity and large scale irrigation, has resulted in the loss of control over these water resources by the local communities – while, at the same time, establishing a centralized administrative system. Many of these grasslands once formed the grazing grounds of the pastoral Toda community. The submergence of these grasslands has forced these communities to abandon their older habitations and reduce their cattle holdings.

These land use and water harnessing changes have also significantly affected the water yield. This is borne out by a landmark study by the Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute in Udhagamandalam[ii]. The study conducted over a period of 24 years found an average annual reduction of 16% in water yield from the eucalyptus planted area over the natural grassland, in the first decade of eucalyptus planting. By the second decade, the water yield reduction went up to 25.4% in comparison to the water yield from grassland.

Speaking to the author, Roy comments that in spite of their contributions to water flows, “Wetlands in Tamil Nadu have no protection. They are often part of revenue public land without any cognizance of their special function". He reiterates the need for further focused attempts to study water flows in the region and support community institutions for protection of local springs.

References:

[i] http://www.imd.gov.in/section/hydro/dynamic/rfmaps/seasonal/mon2012.jpg

/articles/water-and-livelihoods-nilgiris-part-i