To many in the water sector, K. J. Joy needs no introduction. An activist at heart, Joy is known for his untiring rights based work in mobilising communities in rural Maharashtra, and for his research work on water and water related conflicts including inter-state riparian water conflicts.

In a conversation at the Water Future Conference in Bangalore last month, he talked about his journey - from where it all began, to where we stand today, three decades later.

As the water crisis in India and across the world continues to grow, and as equity in access to safe water becomes more and more critical, it is important to keep in mind some basic values that underpin the work that needs to be done. Joy personifies these values, and it is people like him that inspire others to work on these complex issues. We must constantly strive to emulate these values, if we are to ever achieve water security for all in India.

It is also important to remember that working together with local communities, empowering and enabling them to demand for what is rightfully theirs, to take ownership of their water resources so they become self reliant, is still, even today, a powerful tool and process to achieve sustainable social change at the grassroot level. While this work takes time and patience and perseverance, it is critical that we remember the roots of social change in this country - where and how it all started - and always endeavour to stay true to these roots.

How did you start working on water issues?

I got into water issues mainly because after my Master's from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, I was at a crossroads with what to do with my life. That was the time that me and my friend, who became my wife later - we decided to go and work in rural Maharashtra. So we ended up in Sangli district, which is a very highly drought prone region. While working there, we also realised that more than land (because most people there did own some land), the main constraint was access to water. It was also an area where lots of migration was taking place, to cities, especially to Mumbai, and this also coincided with a very prolonged textile worker's strike in the early 80s. All these workers had come back to their villages, and so we started mobilising the workers. All of them began working under the employment guarantee scheme, which was a legal act in Maharashtra (even at that time) to provide employment to people during periods of drought.

We soon realised that an employment guarantee scheme could not be a permanent solution to drought or drought proofing. We did try to change the character of the employment guarantee scheme, saying that for instance, all works taken up under EGS should be agriculturally productive or water-related works like water conservation and the like. We involved the people from the villages in finding the sites where the work could be done. We worked with the people to come up with a people's agenda. We mobilised people to get these things implemented, as a strategy to mitigate drought in the region.

That led us to the whole question of water. We realised that people should at least get some minimum access to water, without which it was [evidently] very difficult to eke out a living. So we tried to look at 3 small rivers there where heavy sand mining was taking place, which spurred a people's movement against the sand mining in these rivers.

Through that movement, a very small dam called the Baliraja Dam was constructed by the people themselves. We called it the first people’s dam in the country. In discussion with the people, we realised that the water was still very limited here, so we asked ourselves - how could we live with limited water norms? How could we ensure equity in access to water? Because water was and is and always will be, a common property resource, a natural resource which everybody should have access to.

So through that whole process and some experimentation we did along with the people, on biomass production, low external input (including water), sustainable agricultural practices and the like, we came up with some norms. Let's say that a family gains access to 3000 cubic metres of water, all their needs can be met. From there, this experiment led to the formation of certain rules and norms that were accepted by the people, that each family could be given a certain amount of water. So that was also the first introduction to equitable water distribution in that area.

We also learned a lot from the Pani Panchayat experience led by Vilasrao Salunkhe during that time. There was some very interesting cross-fertilisation taking place between different experiences. That was also the time when scientists and technologists tried to work with people like us – activists – to critically look at drought to come up with possible approaches to drought proofing.

So that's how I got into water seriously. Then we also worked on dam issues, finding alternatives to very destructive projects like the Sardar Sarovar dam… it was a very highly controversial project involving many conflicts. We came up with an alternative to lower the height of the dam1, which would have reduced the submergence and displacement by about two-thirds of what it is today. We tried to mobilise political opinion around this too, but unfortunately at that time, even the Narmada Bachao Andolan did not take a positive view on this because their stand was still a no dam policy, though the dam was already about 90 metres high.

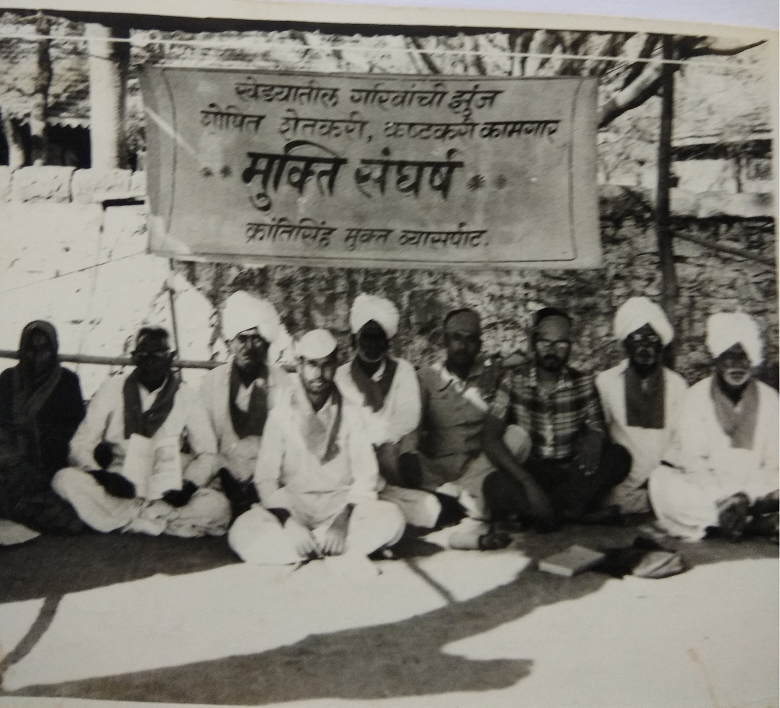

Later the movement spread to 3 drought prone districts of Maharashtra – to Sangli, Satara and Sholapur. I was involved in this movement till about 1990, as a full  time activist mobilising people. One of the distinguishing features of this movement was that we also involved the people in a scientific enquiry into alternatives. We were not just raising demands to the government – we were also showing a pathway to the government on how this could be done. So the people were setting the agenda and mobilising to get it implemented. So I would say my first introduction to the entire water sector, was through my involvement in Sangli district through a mass movement called the Mukti Sangharsh movement.

time activist mobilising people. One of the distinguishing features of this movement was that we also involved the people in a scientific enquiry into alternatives. We were not just raising demands to the government – we were also showing a pathway to the government on how this could be done. So the people were setting the agenda and mobilising to get it implemented. So I would say my first introduction to the entire water sector, was through my involvement in Sangli district through a mass movement called the Mukti Sangharsh movement.

Then I shifted to Pune where some of us set up SOPPECOM – Society for Promoting Participatory Ecosystem Management as an organisation, basically a space to work together and support grassroot initiatives fighting for equity, restructuring [development] projects, etc. At that time we also got into Participatory Irrigation Management, [a concept] that was coming up as a big thing globally. The understanding was that unless the people, the farmers themselves managed their water, the problems plaguing irrigated agriculture would not be solved.

So we did a first pilot in Maharashtra in Ahmednagar district on a very major public irrigation system. Consent was needed from more than 51% of farmers, to form their own organisation. So working through them and with them for about 5 years, and after a whole lot of paperwork, a water users' cooperative society was formed.

Then we tried to scale it up in different places. In Nasik district in the eastern part of Maharashtra, in a place called Ojhar, there was a local organisation called Samaj Parivarthan Kendra, which SOPPECOM worked with. Today, those Water User Associations are seen as the best examples of what Participatory Irrigation Management can do. The entire irrigation project – called the Waghad Irrigation Project – which irrigates about 5-6,000 hectares of land, was taken over by the Federation of Water User Associations. I think this is the first example in India where a Federation of Water User Associations was able to take over an entire dam and its command areas.

We also experimented with how the landless could get access to water rights. We had one interesting experiment in Osmanabad district in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra, where there was a medium irrigation project. There, through discussions and negotiations, people came up with two principles of equity – one, all the people who have land will get, let’s say, enough water for 2 acres of land in the first stage. If there was more water, they would get more, but everybody should get some equal minimum amount of water. They also said that 15% of the water they got from the irrigation department and/or the dam, would be earmarked for the landless people.

Then we - mainly my colleague Seema Kulkarni - mobilised the women there and they formed a separate organisation. Through that, they could use part of the water for various types of livelihood activities. So the lesson for us was that water could be a good entry point to create a much larger base for livelihoods.

Then from there, I’ve been part of SOPPECOM ever since. I was one of the founding members… it was a combination of some very well known people in the water sector at the time like K. R. Datye, Vilasrao Salunkhe, R. K. Patil, S. N. Lele, Bapu Upadhye, A. Vaidyanathan, VB Easwaran and activists like myself, Suhas [Paranjape] and others. So I feel that I was privileged to learn from them and work with them. I always say that I stand on their shoulders. So that has been my journey till now.

How has environmental activism changed over the years? Do you feel environmental movements have more or less of an impact now, given the changing external landscape?

I think the whole question of environmental activism has changed in a couple of ways. One is what is happening internally with the whole activist movement and civil society [at large]. And also there are external factors. In the 80s, for example, many of us were radicalised in the colleges and universities we were studying at, and got involved in these movements. At that time we all felt that a radical social transformation was just next door – it was going to happen in the next 10 or 20 years. We were all idealists, we wanted to change society… there was that commitment that came with that. We didn’t look at what careers we would have, or how much money we would make. None of us had anything. Many of the prestigious engineering colleges or social work institutions or even medical colleges, [were seeing] drop outs who were actually working with people's movements, mobilising people [for social change]. I would say that that was the most fertile period of activism, in the 80s and 90s.

After the 1990s, there has been a declining trend. I am by no means making a moral judgement on the youth of today, that they are not committed. The situation has changed a lot. In those days things were also not so competitive. There was an overall political ambience which was very conducive to this type of activism.

The political landscape has changed drastically in India. Yet movements like the Narmada Bachao Andolan have been fighting this fight for literally decades now. Do you feel there is hope? Do you feel there is another direction activism should take?

I'd say that I'm [still] hopeful that only through movements and activism and collective action can things really change. Of course, knowledge is very important. I'd say one of the changes that is taking place presently, as compared to the 80s and the 90s, is that there are many more people and organisations talking about alternatives, and working with people to articulate these on-ground alternatives. I think that is a new thing emerging – that you can't just oppose a project. You can't just say we don't want the Sardar Sarovar Dam. I think the search for alternatives is now gaining a little more ground than the 80s. A lot more people are searching for alternatives, because otherwise after a point people really get fed up – what are you opposing? Often activists are characteristed in a certain way, that they just oppose.

So finally we also need to define what exactly what we want. That’s what the book Alternative Futures has tried to look at. Resistance to destructive projects should be there, but along with that toiling people also need water, energy and other basic necessities. What are the alternative ways of providing these things? This is also an important question to ask. Resistance to destructive projects and the search for alternatives need to go hand in hand. Some of these things are happening in a small way in different places. Now the real question is how to bring these smaller initiatives together into a coherent exercise.

This is a function for Vikalp Sangam – Hindi for Alternative Confluence - which some of us have started in the last 3-4 years, anchored by Kalpavriksh in Pune. We started Vikalp Sangam to get out of this pessimistic view of things that there were no alternatives, to really explore the different possibilities in water, energy, transportation, city spaces, habitats, culture, language… in all of these spheres there are people doing different things.

But I find that many of these efforts are what I call an NGO-ised model of working. You have an NGO with staff, you get funding, it's a "project-ised" mode of working. In the 80s and 90s it was more of a people's movement. When I was working [as an activist], we were about 5 full timers who lived in a commune. We ate with the people, we slept with them, they would contribute grain, we used to cook for ourselves. But today that culture is gone. Nobody wants to live that way. Even movements are not there much, except maybe the Narmada Bachao Andolan or what we are doing in South Maharashtra… but there aren't many movements with full time committed activists, living without salaries, all working voluntarily.

That character seems to have changed, and that space seems to have been captured by these voluntary organisations and NGOs. I call it an "NGO-isation" of people's movements, which is in a way dangerous because movements should be expressly political and social, [by their very nature]. NGOs should not get into large scale implementation. That is the work of the state. We can do pilots, we can do innovative projects and learn from them, but ultimately the struggle should be with the state to implement these things. There are huge massive NGOs [now] creating parallel systems and processes. They feel they are doing good work. Unless we get out of this... this is where I have a bit of a difference of opinion with many people in NGO circles. Our role [as civil society] is different. We need to show innovation, how to ground innovative ideas, to wait and see whether it works or it doesn't. And then do advocacy through people's movements with the government, on which policies need to change.

Funding for water and environmental issues has also changed considerably in the last few decades too, in terms of the sources of funding. What is your take on fund flows for water in the context of the water crisis today?

I think there is money for a certain type of work. For example, [if] I implement a sanitation project or a drinking water project or a watershed development project, I'm sure there is a lot of money. This is mainly because a lot of CSR money is coming into the sector and they want to show results and put their name on the work. There are other people who don't do this, who work with people's organisations at the grassroot level. Even this work we do on conflicts – nobody wants to touch it. Or work that has a knowledge compoenent. It depends on the type of work. The tragedy is that the larger the organisation, the better placed it is to access the money. The smaller the organisation, the less access it has to funds.

What stands out for you today, as opposed to two decades ago, in the kinds of water conflicts we are seeing today?

What stands out for you today, as opposed to two decades ago, in the kinds of water conflicts we are seeing today?

One of the major gaps I've found after so many years of working on water conflicts, is that we have still not figured out the basis on which to allocate water. If you look at the functioning of different water dispute tribunals in different river systems, they have applied different principles and different norms for allocation of water. So as a society and as a nation, I don’t think we have been able to get that right. I think that is where I'm also interested in ethics and values frameworks – how do we define needs, and on that basis, can we develop a hierarchy of principles like water for life, livelihoods, ecosystems? If we agree on these larger principles [and frameworks], I think there is a way to work out how much the related share of each stakeholder in a water conflict should be. But so far there has been no effort to do that.

In terms of allocation [of water] though, where should the priority or focus be placed [that isn't there / doesn’t exist right now]?

For example now, I'd say in the inter state water allocations – if there's 100 units of water flowing in the river, then that 100 units is divided between the two or three states through which that river flows – the riparian states. But in calculating how much each state should get, what are the actual basic needs of the people of that state, what are the livelihood needs of the people of that state? These are not taken into account when the numbers are being added up. Environmental flows are not taken seriously in the Indian context even now. Newer issues like climate change complicate the matter further. Data is no longer stationery, making long term trends and averages key to evidence based decision making.

Just this year, the government amended the 1956 Interstate River Water Disputes Act, so now the main focus is not on norms or basis of allocation [of water], but on the structure of the tribunal. For example, each river basin would appoint a separate tribunal in a conflict. But today they have one permanent tribunal with a provision for benches. The whole idea is to shorten the time it takes to resolve conflicts.

One positive development, however is that they’re also talking about data today, that we need a centralised system for data that we agree upon. It becomes difficult when states don't agree on the river data being presented. Also, there is a provision for negotiating before the tribunal actually starts adjudication. Is there any space to talk it out first?

While there are some positives, the main gaps still remain – how should water be allocated? Intra and inter state equity in river basin conflicts also needs to be looked at more seriously. We need democratic spaces for people to come together, share data, experiences, negotiate their needs – we don't have that.

Do these interstate tribunals represent all stakeholders?

No – it's basically an adjudication process by the tribunal headed by a judge. They appoint a 3 member committee. Each state puts up a team of highly paid lawyers to argue their case. Another critique I have is that only the state actors are involved in this process. Non-state actors like academics, NGOs, etc. are not involved at all. In the west, stakeholder processes are taken much more seriously and they are binding – if you have to take a major decision, like dam removals for instance in the US – there is a stakeholder process where they see to it that all important stakeholders are involved, different scenarios are presented, and then the least cost option is considered. There are agreed upon processes and principles that guide decisions which are then final and binding.

We don't have these same legal provisions [in India]. A classic case is the Cauvery Family that also came up with a sharing formula, but that didn't align with the tribunal process, which was a parallel process. We need to ensure legally binding stakeholder processes. The main question is – how do we create legally mandated institutional spaces to mediate these conflicts fairly? Conflicts by and large are treated as criminal cases – we don’t have any other processes. That's the main gap.

References:

1. Sustainable Technology: making the Sardar Sarovar Project Viable – A Comprehensive Proposal to Modify the Project for Greater Equity and Ecological Sustainability; Suhas Paranjape and K. J. Joy; Centre for Environment Education; 1995

/articles/conversation-k-j-joy-soppecom