Springs Menu

Springs in India

There are five million springs across India, based on current estimates. From the Nilgiris in the Western Ghats to the Eastern Ghats and Himalayas, springs are a safe source of drinking water for rural and urban communities. For many people, springs are the sole source of water.

For example, ninety percent of drinking water supply in Uttarakhand is spring based, while in Meghalaya all villages in the state use springs for drinking and/or irrigation. Vital components of biodiversity and ecosystems, springs are also how many rivers and streams are generated. Most of the rivers in central and south India are spring-derived including the Krishna, Godavari, and Cauvery.

As the springs of many mountain states in India continue to dry up, the state of Meghalaya takes the first step pulling strings together to revive its springs heavily depended on. The Government of Meghalaya is trying to bring in stakeholders from all concerned areas to work on this. However, with most of the land being privately-owned, the approach would have to be carefully designed.

Despite the key role they play, springs are in crisis. Spring discharge is declining due to groundwater pumping under increased demand, changing land use patterns, ecological degradation and a changing climate. A survey in Sikkim found that water production has declined in half of all springs in the state – a dangerous sign that aquifers are depleting in a state almost entirely dependent on springs for drinking water.

Similar effects are being observed in nearly all mountainous regions of India. In the Western Ghats, once perennial springs are becoming seasonal, leaving communities struggling to meet demand. Temples built on perennial springs are now dry as upstream wells compete for drinking and irrigation water. Exacerbating the problem, water quality is also deteriorating under changing land use and improper sanitation. Springs traditionally used as a village drinking water source are being abandoned due to the close proximity and contamination from latrines.

Any reduction in water supply or water quality will have profound impacts not only on village drinking water, but also on regional livelihoods, health, biodiversity, agriculture, tourism, power generation, and industry.

The Springs Initiative is working to promote awareness of the importance of springs, and to build capacities to protect and develop springsheds across the country. At the community level, most spring protection efforts utilize the similar programmatic approach:

1. Communities are engaged through hydrogeology to map springsheds

2. These areas are targeted for restoration, protection and/or augmentation of recharge

3. Communities are part of the entire process, including the field hydrogeology, in attempt to demystify the science and make it open source

4. Local institutions then take up the monitoring and management of springs after significant training and engagement.

5. Many community members become groundwater literate and share knowledge with others

Springs owe their existence to the nature and structure of the rocks surrounding them. The science of this interaction of geology and water is called hydrogeology. An understanding of this science is crucial to understanding springs, their behaviour, and the means of their conservation.

We seek to demystify the science of hydrogeology. This puts the ability to map geology, aquifers and recharge areas directly into the hands of community members. So far, this approach of training 'parahydrogeologists' has empowered field-based development organisations and village spring communities to efficiently manage their springs.

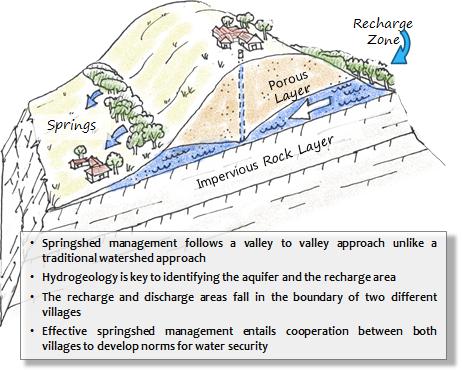

'Springshed' is a portmanteau word that describes the catchment area of a spring, or the land from where it obtains its water. Springsheds differ from watersheds in that they are not necessarily the same as the valley inhabited by the spring. It is common in fold mountains like the Himalayas to have a spring and its springshed in two different valleys. This necessiates a knowledge of hydrogeology and meticulous mapping. Once the springshed is identified, the goals of springshed restoration are akin to those of watershed management:

1. Reduce soil erosion, increase vegetation cover and soil organic matter

2. Increase natural infiltration of water into the soil and recharge of the aquifer

3. Protect the area to allow ecological restoration and prevent pollution of the groundwater and surface runoff by maintaining cleanliness in the catchment area.

4. Augment natural infiltration and recharge through best practices

The success of spring restoration, and of the Springs Initiative hinges on the enthusiastic participation of all the entities concerned. Firstly, these are the communities that use springs. It is important that they are convinced of the need to conserve their springs, that they understand how it is done, and that they be willing to assume the responsibility of managing their springs. In most cases, therefore, the demand for spring restoration needs to come from the communities.

Non-govermental organisations, including funders, researchers, and field development organisations all have a role to play in facilitating the exercise and enabling communities to manage their springs.

However, the scale at which these organisations can operate is necessarily limited. The crises surrounding water make it necessary that springs management be taken up at the regiional scale. This is where governments come in. Sikkim and Meghalaya have demonstrated that state governments can take the lead in participatory, science-based management of springs.

Many community members have an inherent understanding of hydrogeology and, after some exposure and informal training, they go on to become para-hydrogeologists. There are self help groups (SHGs) in Uttarakhand who can explain rock types and formations as well as many geology graduates. There are farmers in Maharashtra who are now mapping geologic contacts to help other villages identify their springsheds.