Drought conditions are not new to Bundelkhand. The acute situation now is a convergence of three types of droughts – meteorological, agricultural and hydrological - cumulatively coinciding as witnessed in Nunagar village in Panna district, Madhya Pradesh. We saw hundreds of vessels queuing up at the panchayat well. A closer look revealed that it is not well water that was being collected here, but people were lining up to fetch water from a piped source that is released to the well. All wells in the village have become seasonal due to a dip in the water level and are marked by poor water quality.

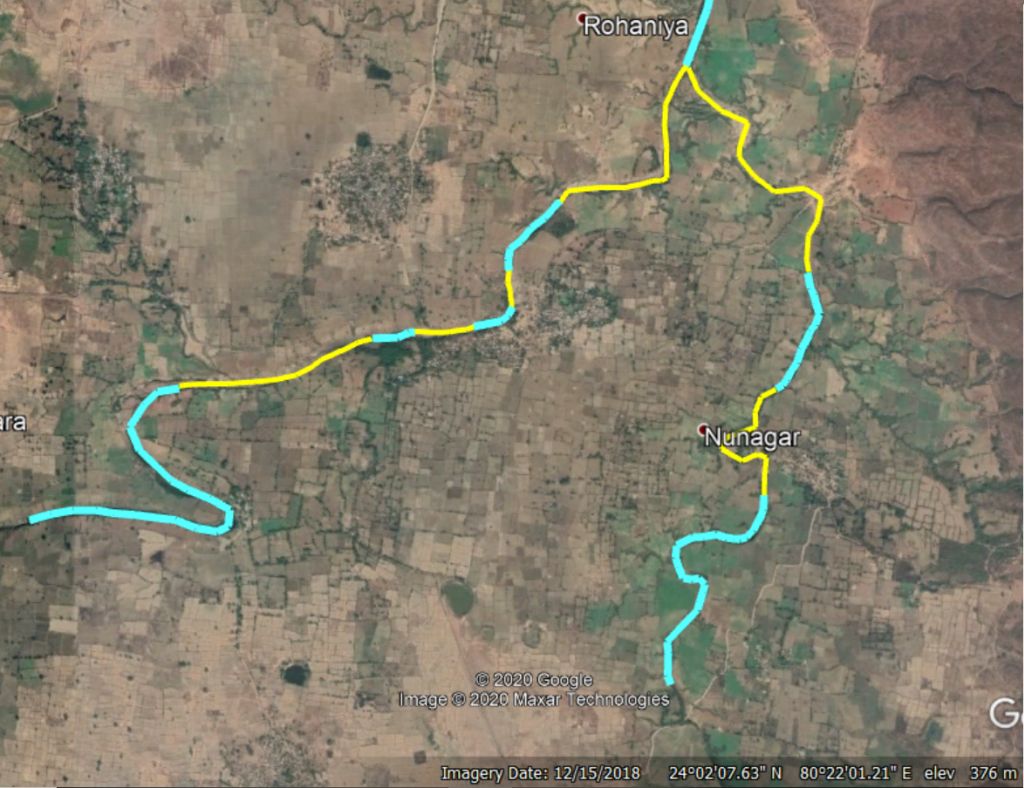

Nunagar is sandwiched between two major rivers Ken and Aloni as shown in the map and blue patches are the places where water used to be available perennially in the form of natural solution cavities called kund. Now rivers go dry in summers due to over-exploitation in the rabi season. With the advent of a public piped water supply by the gram panchayat, traditional water management systems around open wells, talab, kunds are vanishing. The promise of “potable” water turns into a “pipe-dream” that fails due to various reasons - lack of technical, economic and institutional capacities.

The failure of agriculture crop despite average rainfall, as per villagers is indicative of agriculture drought. The depletion of water resources - drying up of rivers and wells to the extent of creating acute drinking water scarcity over the years indicates that drought has altered into long-term hydrological drought in Nunagar village.

Multi-faceted drought

The narrative of Bundelkhand region around drought has to be changed. Because it is not only about meteorological droughts, but temporal and spatial high variability of rainfall across the region as a result of climate change, which is accumulated into the long term agricultural drought and hydrological drought.

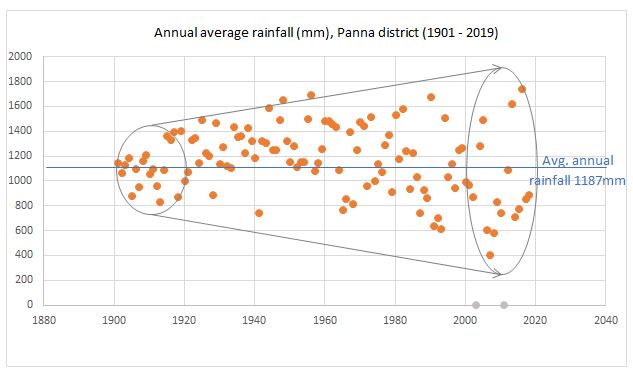

From the chart below, it can be inferred that there is a deviation of annual rainfall from the average, each year in the last two decades in Panna district. The high rainfall years are marked by excessive rains bringing in flash floods and low rainfall years are characterised by very poor rainfall leading to meteorological drought. Both the conditions are highly adverse for normal agriculture practices. As per the primary data collected by the People’s Science Institute between the years 2012-2015, rainy days are shrinking from 55 to 25-30, dry spells are increasing (varying between 15-25 days) and 90-95% of rainfall occurs in the month of July-August. The lack of drought-proofing measures to deal with such varying rainfall and increasing long dry spells in kharif season, has led to the phenomenon of agricultural drought in the region.

In many villages of Shahnagar block of Panna district, the villagers witness the consequences of this variability. “Due to the delayed rainfall, the sowing time is extended that leads to the damage of a six-month duration arhar (pigeon pea) due to frost in December,” says Ratan Singh from Banjari village. Even though Bundelkhand region has a rich legacy of traditional knowledge, but some of the recent phenomena like delayed rainfall and frost triggered due to climate change do not figure as a part of the accumulated wisdom of the local farming systems.

Climate-resilient crops like kodo/kutki (little millets) were the major crops along with maize, pulses, and barley in the region. Shifting from millet to water-intensive crops like paddy and wheat have undoubtedly increased the demand for irrigation facilitated by the advancements in irrigation facilities, availability of diesel pumps at subsidized rates, and power rationing for running electricity pump-sets. However, the available water is falling short of demand leading to a slump in productivity and often crop failures.

The compounded effect of these failures has aggravated the chain of consequences in the prolonged period such as a scarcity of fodder available for livestock, which is increasingly seen as unproductive by owners. Hence, the owners are not much bothered even when they don’t return from grazing. As a consequence, one can find innumerable carcasses of animals in and around Banjari village. The tale is similar in umpteen villages of the Bundelkhand region.

The compounded effect of these failures has aggravated the chain of consequences in the prolonged period such as a scarcity of fodder available for livestock, which is increasingly seen as unproductive by owners. Hence, the owners are not much bothered even when they don’t return from grazing. As a consequence, one can find innumerable carcasses of animals in and around Banjari village. The tale is similar in umpteen villages of the Bundelkhand region.

Desertification of several villages in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh part of Bundelkhand for drinking water, water riots in rural interiors of UP Bundelkhand in summer of 2019 despite average rainfall year of 2018, National Institute of Disaster Management’s claim that 7% villages had enough water to meet domestic needs, all these events testify that drought has manifested into long term hydrological drought.

New demands for water are also emerging with flagship programmes like the Swachh Bharat Mission and now the current pandemic of Covid-19. Although Banjari village has been declared as open defecation free due to full toilet coverage, very few use it. On asking the reason for non-use, Sukhdev Singh says “why to waste a bucket of water when a mug can do the job?”

The Information, Education, Communication (IEC) strategies deployed by Swachh Bharat Mission has designated volunteers who go around photographing open defecators to ‘name and shame’ and thus bring ‘behavioural change’ to use toilets. The experience from the village points that it might not be cultural reasons, but shear material realities that constrain use of toilets, the major one being non-availability of water. The thought of using extra water to maintain hygiene to avoid Covid-19 is beyond the imagination of villagers (who have access to hardly 20 lpcd as against the norm of 55 lpcd as per Jal Jeevan Mission, 2019), making them more vulnerable.

Reasons for crisis

Beyond these impressionistic accounts of drought in Bundelkhand attributed to the climatic conditions, the long-term structural problems have to be highlighted. Caste-based social structure leading to unequal distribution of resources, neglect of traditional water structures, lack of proper water management and drought-proofing measures, changing cropping pattern to water-intensive crops due to the dominant green revolution approaches of the agriculture department and lack of proper coping mechanism have deepened the crisis.

One of the largest programme carved for the drought mitigation in the region, I.e. Bundelkhand Special Package (BSP) has failed miserably as it emphasized more on cemented water infrastructure (57% of total investment) as opposed to the reigning thrust of watershed management (9% of total investment) and local water harvesting structure (2%). A major portion of the rest of the investment goes into agriculture infrastructure like Mandi, warehouses, etc. The recent policy shift from “integration” to “irrigation” in the mainstream policies like Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sinchai Yojana has been adopted in the regional drought mitigation efforts, which may not fetch any benefits for the regional crisis.

Alternatives do exist

Historically, the traditional water structures in the form of Chandeli/Bundeli tanks have been absorbing the shocks of erratic climatic events. These tanks were used for recreation, domestic use, and improvement of the groundwater regime in the plateau area to facilitate well irrigation. Although these tanks cannot be romanticised as “the only” solution to the diverse water woes in the region, it underlines the principles of community-led water management, equity, sustainability, and democratic participation in water management.

Alternatives like traditional Chandeli tanks, farm ponds, watershed management, climate-resilient agroecological interventions, etc., are well documented and demonstrated in various geographies and agro-climatic conditions of the Bundelkhand region by formal and informal institutes. But they have not been scaled up through government programmes like the Integrated Watershed Management Programme and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. The investment patterns are skewed and have more emphasis on infrastructure-based investment and individual beneficiaries that are prone to be captured by big farmers.

The alternatives have to be re-adapted to the understanding of drought in the wake of climate change and a regional policy vision is needed as against blanket application of schemes by respective states. It may start from the watershed basin and can be narrowed down to water management at the farm level, where many appropriate technical solutions are available. But it has necessarily to be hinged in principles of community-based approach in both supply and demand management.

Other measures like judicious water use, shifting to non-water intensive crops, addressing rainfed farming systems, abstaining from using deeper aquifers, collective actions centered on sustainability with democratic participation, etc., have to be incorporated into new regional policy vision. The communities have to be part right from planning to governance. At the same time, the local strategies have to be dialectically abstracted and collated at appropriate levels of watersheds and river basins and through appropriate political and administrative institutions to escape the populism that everything can be tackled at the local and by the people.

Authors

Seema Ravandale, Head, Innovative Project Group, People’s Science Institute, Dehradun

Dr. N C Narayanan, Professor, CTARA, IIT Bombay, Mumbai

Rohit Kumar Prince and Rehma Sahoo, M.Tech 2018-2020, CTARA, IIT Bombay, Mumbai

Note: Two students, Rohit Kumar and Reshma Sahoo from CTARA, IIT Bombay spent two months in the tribal villages of Panna district in the summer of 2019. The article draws insights through their lenses and contemplates the larger issue of drought in Bundelkhand.

/articles/reflection-multi-faceted-droughts-bundelkhand-region