Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote that he who has a ‘why’ to live can bear almost any ‘how'. A strong reason, motivation (why) and curiosity lead to actions that pave the path (how) to achieve any desired goal.

Sounds ideal and perfect! And we would like to believe or hope that everyone approaches the decision-making process concerning natural resources the same way. Why are then most decisions on water resources in India perceived as incoherent by the larger society? Let us try to understand the extent of perplexity and complexity involved in this domain, deeply, by answering two questions:

- First, what are the barriers that hinder good decision-making, in general, and about complex natural systems, specifically?

- Second, what elements can create an apt space, which might facilitate better decision-making?

How do we humans make decisions? And why are we tilted towards making bad choices?

As humans, we take thousands of decisions every day. These choices shape our future. Research has established that the task of decision-making is a multifaceted and cognitively overwhelming process. For example, deciding to build a dam or not! Or implementing a watershed program is a humongous and resource-intensive task. A few of the fallacies and hidden traps are explained below, which impede us from making a good decision.

As humans, we take thousands of decisions every day. These choices shape our future. Research has established that the task of decision-making is a multifaceted and cognitively overwhelming process. For example, deciding to build a dam or not! Or implementing a watershed program is a humongous and resource-intensive task. A few of the fallacies and hidden traps are explained below, which impede us from making a good decision.

Choices and time: Researchers suggest that trying to decide between too many choices can lead to cognitive impairment. Moreover, we are inherently wired to perceive cost-benefit in the short term versus long term differently. We are thinking about electricity generation (short term) and not conserving the ecosystem (long term) simply because of our flawed perceptions1. Maybe, it is not about morality after all!

Environment: The environment in which the decisions are made also plays an important role. When our environment is threatening, we get into a defensive mode and our ability to respond rationally is hijacked by fight or flight responses. The amygdala in the brain, which generates a fear-based response, gets activated. Whereas a relaxed, threat-free environment activates the prefrontal cortex and can lead people to make better decisions.

Since we are cognitively wired to respond this way and the fact that socio-ecological systems are inherently complex adaptive systems (CAS), it becomes all the more important to have an apt environment where participants can deliberate and can make more mindful decisions. This can lead to better collaboration and conflict resolution. It is also found from cognitive studies that people find it easier to make decisions when things are in order2.

Conditioning biases: Perhaps, not all of us perceive most inclusively and consciously. Are we biased as engineers or economists due to our training? We don't behave the way it is expected. In fact, most of the time the tendency is to misbehave!3

Complexity and data overload: Now, imagine a system so complex that it is difficult to understand all of its variables, interactions, and different subsystems within the water ecosystem. As one of the links in this complex system, we have to decide on the overall behaviour of the system, which is difficult as our conscious mind cannot hold big data.

Diverse storylines: An important point to ponder is that we humans are at this stage of evolution because we believe in cooperation. We can create, imagine, and believe in stories and align ourselves with them. For example in the context of water, imagine the different stories that we all have about how water should be distributed. This diversity arises from the contexts we are situated in and make their way into decision-making processes through policy advocacy.

The idea of Decision Support Space (DSSpace)

Historically, as a society, we used to live very closely with nature. The rule was that if you don't understand it, leave it untouched, make it sacred or holy or at least try and stay in harmony with it. We can see several examples still alive in India, as illustrated in Survival lessons by the Peoples’ Science Institute (PSI). But we don't do that anymore.

Decision Support Systems (DSS), in recent times, have been seen as magical boxes that can give objective answers to complex situations involving CAS. They have been focused on engineering methods and do not cater to societal preferences and environmental values.

They have not been able to reflect the possibility of tradeoffs or flexibility to shift solutions. The momentum of outcome orientation does not allow them to adapt to the shifts in the system itself.

Given the above context, there is a clear need to initiate and nurture a holistic process of continued engagement within the water sector in India. According to psychologists, such an engagement should have two ingredients for learning: frequent practice and feedback. The water decision-makers we admire have become so by developing a gut feeling through constant engagement with different sets of knowledge.

There is a need for space where different stories can co-exist and co-evolve. Space where efforts and energy can be conserved and channelized to make better decisions. And this space can be utilized to create a story that is self-evolving, keeping in mind the diversity of participants involved and the dynamic policy space. This is also one of the inspirations behind Decision Support Space (DSSpace).

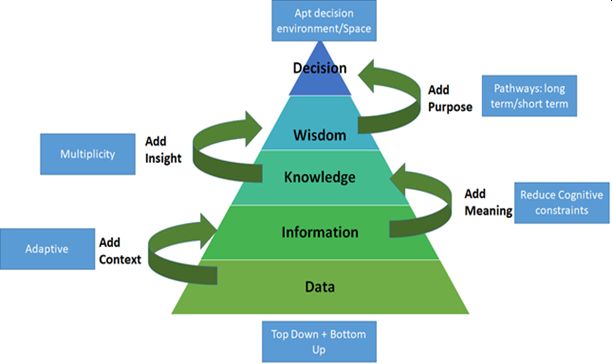

The following represents a conceptual diagram of the DSSpace. It seems outrageous though! But as Einstein said ‘things should be simple but not simpler’!

Elements of a good DSSpace

Purpose-driven outcomes: Every decision needs a purpose. This should be rooted in values of - equity, justice, transparency, inclusivity, systems thinking, and rights-based approach of rivers, marginalized communities, and above all kindness. Having remotely sensed information, for example, doesn’t hurt anyone! But, we should not become slaves to this data and use it to assist the decision-making process.

Top-down and bottom-up approach: Research suggests that social learning is crucial for adaptive water management. In the case of top-down, we can learn a great deal from comparative hydrology or learning from the data in different watersheds. For bottom-up, fieldwork becomes important. Citizen science should also be a part of DSSpace and synthesized information should be shared back with people at the grassroots.

Adaptability: CAS is ever-evolving and new variables can appear at any time. A DSSpace for CAS should be flexible enough to respond to uncertainty4. For example, COVID-19 is a completely unimaginable scenario.

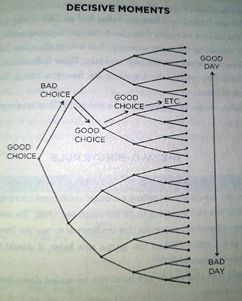

The figure illustrates something interesting! It is possible that we started with the right intention and hoped that we would make good policy or decisions but somewhere down the line, we learned that it's not working. So, there should be a way where we can toggle to choose alternative pathways. We can be allowed to make mistakes but be mindful to not take them beyond the tipping point. Nothing should be hard-wired.

Red Flags: DSSpace should be able to put red flags on inherent cognitive biases and blind spots of decision-making processes.

DSSpace should have a multiplicity of vantage points to break the silos.

The diverse perceptions of various participants are essential for a holistic understanding of the system. The diagnostic kit is important (GIS, data) but so is perception.

Long term and short term pathways: It is all about prioritizing and orienting goals based on providing solutions or responding to needs. A DSSpace should be able to lay out short term tangible, need-based goals that are aligned with long term value-driven goals. A multiplicity of group-based values can also help here to critically think about long term decisions!

The DSSpace we have in mind should not only be a state of the art technology-driven but also an inclusive multi-disciplinary space for bias-free, non-fear based decision-making. Creating such a space can aid in more mindful decisions and policymaking regarding events like droughts or floods and help minimize conflicts and enhance cooperation in water.

This is a work-in-progress. Stay tuned for our upcoming research article.

Bibliography

1. Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

2. Harari, Y. N. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Random House.

3. Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Penguin.

4. Thaler, R. H., & Ganser, L. J. (2015). Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics. New York: WW Norton.

Footnotes

1: For every individual, Perception is the only truth, rest is all distortion!

2: “A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs. Laziness is built deep into our nature.”- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

3: “What makes the bias particularly pernicious is that we all recognize this bias in others but not in ourselves.” - Richard H. Thaler, Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

4: “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.” - Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast, and Slow.

Authors

Divya has completed her Ph.D. from the Department of Natural Resources, TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi and is a recipient of a Ph.D. research grant from the Himalayan Adaptation, Water and Resilience (HI-AWARE) Research on Glacier and Snowpack Dependent River Basins for Improving Livelihoods program.

Neha Khandekar is currently working as SRA at ATREE under a project Ph.D. position. She is researching water conflict-cooperation in the Cauvery basin using the socio-hydrology lens.

/articles/decision-support-space-concept