1972 was the year. A massive hit, a landmark movie in Dr. Rajkumar's cinema career was realeased: Bangarada Manushya (The Golden Man).

With many melodious and meaningful songs, the theme was something close to one's heart - an urban youth returns to his ancestral village, takes up agriculture and works for the welfare of the village.

Dr. Rajkumar was ably supported by Mr. Dwarakesh in a comic and supporting role.

Two hours and six seconds into the movie is a comedy scene. The supporting actor decides to end his life because his father doesn’t approve of his marriage. The father’s concern is that the son is immature and irresponsible.

The actor goes to a nearby lake to commit the heroic act. The tank is full but the water is cold. He prays for the Sun God to warm the water, so that he can end his life happily and comfortably. He sits and waits for the water to warm up...

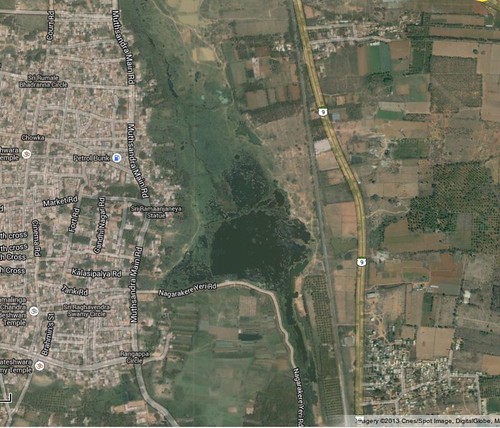

If the film were shot in the recent past and not during the 1970’s, the image above will show the actor staring down not at water but at a brown vast expanse of land! Where would the comedy be in that and who would have the last laugh?

This lake - if we can call it a lake anymore - is the sixth among twenty five cascading tanks, which culminate in the Naagarakere tank in Doddaballapur town. These intricate chains of tanks are spread across two streams, both originating from a nearby hill called Channa Giri. Part of the same range that also hosts the more famous tourist hill, Nandi Giri (Nandi Hills), these twin streams feed water into the twenty five tanks including Doddaballapur town’s Naagarakere and eventually join the Arkavathy river.

Part of the same range that also hosts the more famous tourist hill, Nandi Giri (Nandi Hills), these twin streams feed water into the twenty five tanks including Doddaballapur town’s Naagarakere and eventually join the Arkavathy river.

The Arkavathy is a major tributary of the Kaveri. For the former, a river which runs for 190 kms before joining the latter, this cascading tank system is vital. One can only admire the wisdom of the past generations, which identified crucial places for building these chains of storage tanks, that kept the channels clean so water could flow. “During my childhood days in 1980s, every single house had to nominate a person for clearing the Raja Kaaluve [channels] and desilting the tanks before the monsoons,” recollects Shri Nataraj, a reporter at the Kannada daily Prajaavani who is also an activist and a resident of Doddaballapur. Today, he says, people have even forgotten where the channels are.

Naagarakere is one of the largest among these tanks, and is situated in Doddaballapur town.

A freshwater well within this tank was once the primary source of drinking water for the dwellers of this ‘Silk City’. Middle aged town dwellers remember drawing water from this well, called Gosai Kunte during their younger days. But, since the early 90’s, this tank, as also the preceding ones in the chain, started retaining lesser water each year. These tanks have been practically dry over the last few years. A brown playground rather than a water body, is what the younger generation remembers.

This transition from a life-giving water body to a barren field is the 'boon' of urbanization. Encroachment is the first progeny of urbanization - grab as much land as soon as possible. And, water bodies are the sitting ducks (pun intended).

The first tank in the series, Chikkegowdana Kere, has at least two farmlands which are built right on the tank bed, or have encroached a significant part of it. A stream flowing near the Channa Giri, which fills up this tank and eventually Naagarakere, is diverted into these farms.

If sufficient water does not even reach the first tank, how can it flow into Naagarakere, which is 19 kms downstream? And consequently, how can the river Arkavathy be rejuvenated?

The situation is the same in Naagarakere too. The etymology of the name Naagarakere, some say, is Nagara (town), and Kere (tank) - it was the tank of the town, the source of its drinking water. Today, it is filled with industrial effluents and the town’s sewerage.

Drilling borewells, a habit systematically encouraged and nurtured since the advent of the much-lauded Green Revolution, has resulted in rapid depletion of groundwater. There are around 225 borewells in this town, with an average depth of 900 feet. 112 of these were dug by the City Municipal Corporation (CMC), of which only 40 are yielding water. These are used to meet around one-third of the city’s water demands. Around 50 borewells are used by private water suppliers.

Sand mining is another culprit. According to the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board, sand-mining is prohibited around a 1km radius of the Arkavathy’s course but whether the prohibition is enforced, is anybody’s guess. The tank in Chikkaraayappana Halli, the first in the series above mentioned, shows clear signs of mining by brick factories.

How and why this happened

Somewhere over the last few decades, our perception and beliefs about these water bodies changed. Earlier, we had a rich culture and wise traditions that nurtured communities around lakes, open wells, and rivers. Water bodies were revered and they brought people together. The perception today is different, says Mr. Doddy Shivaram, a fellow of Svaraj, a journalist and an active member of Arkavathy Kumudvathi Nadi Punashchetana Samiti.

He recollects his younger days in K.P Doddy village in Magadi Taluk, where the community came together every year to desilt the tank and clean its surroundings. The community owned the water bodies and the community maintained it. Today, the popular perception is that the tank is government property and it is the government’s duty to provide water. This change in perception resulted in years of neglect.

Nevertheless, all is not lost. Nature is forgiving, if only we assist her constructively or, at least, stop heedless destruction in the name of development. The sight of various organizations and individuals working in this region, whether jointly or otherwise, is heartening. Citizen groups, along with the help of NGOs, have better understanding of the importance of these water bodies and the socio-cultural aspects related to water management. Svaraj (Society for Voluntary Action Revitalization and Justice), supported by Arghyam have mobilized citizens in this region.

A prolonged effort to highlight the issues have drawn the attention of the government as well. The Cauvery Neeravari Nigam Limited, a unit under Water Resources Department of Government of Karnataka, has taken up the task of clearing the channels connecting the tanks, in a bid to fill the cascading tanks, and rejuvenate the Arkavathy river.

Such efforts have started bearing results; there is some water even at Naagarakere, after this year’s monsoon rains.

If efforts from the past couple of years have borne this result, one can only imagine the benefits of sustained and serious efforts in a similar direction. Out of 190 acres of tank area, 40 acres have already been encroached upon. The fencing, which was built recently, will help prevent further encroachment.

Apart from the quantity of water - which can be increased by removing the encroachments and keeping the connecting channels clean - the quality of the water remains a serious concern. 92% of the water sources are not fit for drinking, and the CMC officials admit it, too.

The CMC, which currently caters to only 51% of the city’s drinking water demand, can convert this tank into a useful storage point for further purification and supply. The town’s entire dependence on groundwater, which is the present situation, is not sustainable. Construction of the underground drainage network and Sewage Treatment Plants (STP) will stop the flow of sewerage into the tank. Stopping the flow of industrial effluents is equally important, and stricter action must be taken against the polluting industries.

Community’s efforts in building pressure groups, and taking ownership, at least partly, for the maintenance of the lake, will go a long way in solving the city’s drinking water issues. An example could be the perceptible decrease in water level in Shri Kalappa’s well near the first tank, possibly due to neglect of conservation efforts.

The microcosmic efforts of the community, civil societies and the government to restore and protect these tanks, aids the macrocosmic effort to rejuvenate the Arkavathy itself. The need is to see the true value of water and act accordingly. The problem is undue focus on land, and sheer neglect of water bodies.

Just Google for the term “Arkavathy” and see for yourself - barring the Wikipedia link, the 9 other links on the first page links only to Arkavathy Layout and its allottees' issues.

As the joke goes, even Google can't find water in the Arkavathy today.

View the entire photo set here.

Acknowledgements, in alphabetical order:

- Doddy Shivram, and Svaraj team, for taking us to the places mentioned in the article, and helping us meet the concerned officials, and providing all necessary information;

- Kavita Kanan and Ashis Panda, for giving me the opportunity to write this article;

- Rahul Bakre, for giving a birds-eye view of the activities related to urban management in the town;

- Uzra Sultana, for meticulously collecting vital information used in the article;

- Vishwanath Srikantiah, for it was his idea to cover this interesting topic, and for his overall guidance.

/articles/comedy-and-tragedy-doddaballapur-tanks