Dilemma facing NGO action

Watershed development is not merely a matter of harvesting rainwater. Its success crucially entails:

• working out collective protocols of equitable and sustainable use of surface and ground water

• bringing together of scientists and farmers to evolve a dryland agriculture package and a host of other livelihood options

• detailed land-use planning at the micro-watershed level and

• the mobilisation of rural communities in the direction of the disadvantaged

Many NGOs in India have set examples in one or more of these challenges. But one has to be very careful here. Currently, the voluntary sector is seeing a proliferation of agencies, many of which are of a dubious nature. It is not clear that a commitment to serve the poorest has brought them to this field. It appears that the larger cloud of corruption enveloping society in India has made its entry into the voluntary sector as well. Many NGOs are simply fly-by-night operators who obtain government grants and disappear without a trace. There are others who play a contractor-type role, thriving on huge government grants and resultant commissions.

Grass-roots agencies have, therefore, to be very carefully identified, selecting only those with many special qualifications:

• solid field presence and deep commitment, so that the benefits can be sustained in the long-run

• requisite technical skills, with a capability of conducting meaningful interface with scientists, translating their inputs into specific field conditions, marrying the insights of scientists with those of the farmers and providing detailed feedback to scientists

• capacity to carry out empowerment programmes for representatives of Village Level Institutions (VLIs)

• capability of networking with other genuine grass-roots agencies, so that the benefits can be transmitted far and wide, with significant multiplier effects.

After all, we do not want to create oases of excellence – rather the attempt must be to develop “living laboratories of learning”, from which more and more people benefit, far beyond the immediate location of the grass-roots agency. Most NGOs tend to be very localised in their operation. Many of them are excellent grass-roots mobilisers working as community-based organisations (CBOs). They can have a very important role to play in building capacities of PRIs for effective governance of rural areas. And those who try to work on a large scale suffer the problems of neo-governmental bureaucratisation. The trade-off between scale and quality appears irreconcilable.

Thus, while the role of NGOs can be very important it is clear that two problems need to be addressed:

• how to find genuine NGOs with quality

• how to ensure that NGOs do not end up becoming mere oases of excellence

Challenge of upscaling with quality

A very interesting innovation in this regard has been attempted by the Council for Advancement of People’s Action and Rural Technology (CAPART). CAPART is a semi-autonomous body registered under the Societies Registration Act, working under the aegis of the Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India to provide financial and resource support exclusively to voluntary organisations for rural development. CAPART is a unique institution at the interstices of state and civil society in India. On the one hand, it represents a reaffirmation of the responsibility of the state in facilitating the role of voluntary agencies in national development. On the other, it affords a space for civil society institutions in decision-making regarding critical policy issues concerning rural development in India. If one recognises that grass-roots civil society institutions have a vital role to play in enforcing accountability of state institutions and in galvanising rural development by setting exemplary standards of technical excellence and people’s participation, then the role of CAPART becomes extremely important.

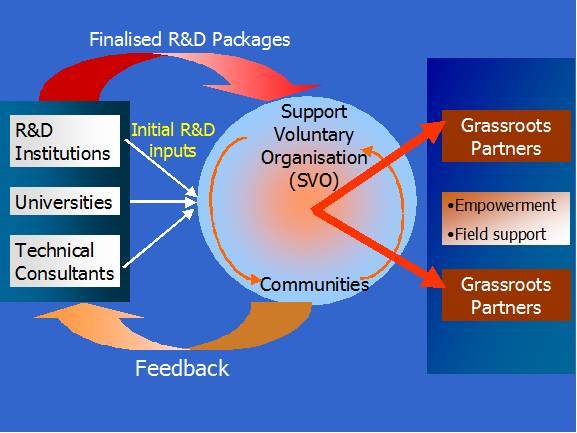

CAPART has sought to overcome the problem of quality of agency and operational scale through the concept of the Support Voluntary Organisation (SVO). CAPART has recognised seven SVOs for its watershed programme [1]. The role of SVOs is to search out and link up the thousands of disparate, small but sincere groups, working in far-flung corners of the country,

Figure 1: Support Voluntary Organisation

and provide them the necessary wherewithal to both implement watershed programmes in their areas and mobilise rural communities for this purpose. These agencies could include not just grass-roots NGOs but also Community-based Organisations, Watershed Committees, Forest Protection Committees, Self-help Group Clusters, Gram Panchayats or the committees of the Gram Sabha that look after natural resources. The SVOs would provide them all logistical support from resource mobilisation to action plan implementation. The responsibilities of SVOs are to search for and screen prospective partners with a good track record, promote the watershed programme among them, by pro-actively seeking them out, orienting them into the programme and assisting them in preparing watershed action plans; to impart training on watershed development to agencies engaged in the programme; to provide technical and other required support through field visits to the watershed area at regular intervals; to act as institutional monitors for the watershed programme, evaluating the performance of agencies engaged in the programme or those wishing to join it; to conduct research on various aspects of watershed development; to disseminate widespread awareness by acting as ambassadors of the watershed approach. Each of the SVOs can be visualised as a nucleus, giving rise to many nuclei of empowerment all over the country. Through the SVO concept we can project how the watershed programme could be upscaled over, say the next 20 years, with carefully selected partners being in the forefront of implementation. Each SVO can conceivably support 200 partners over such a period, each of which could in turn cover 10 watersheds of 2500 hectares each. If we have 20 SVOs, this could add up to 100 million hectares of land being covered over the next twenty years. Also each SVO will not have to hand-hold each of its 200 NGO partners at the same time. There will be a typical phasing out period of 5-7 years, after which the NGO will be on its own, and will, in turn, empower other agencies in its area of work. This would be no mean achievement. Apart from its direct impact, such work once it reaches a critical mass, could have a major demonstration effect on government-run programmes as well [2].

Baba Amte Centre for People's Empowerment

It is with this vision that the Baba Amte Centre for People's Empowerment (BACPE) was born in 1998. At present, BACPE is working with 50 CAPART partner organizations in these states and supporting watershed development projects worth around Rs.130 million spread across half a million acres in 50 districts. •Over the past 8 years we have played the SVO role for 122 partners (including those not in the CAPART stream) drawn from 72 districts of 12 states. These partners are Voluntary Organisations and Community Based Organisations who are receiving the benefit of training and support (hand-holding) from BACPE. They are from the states of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Karnataka, Mizoram, Maharashtra, and Nagaland

Our support to NGOs in their own area of operation takes place at every stage including:

search

screen

identification

orientation and introduction to watershed development

proposal preparation

preliminary desk appraisal of proposal

pre-funding appraisal

post-sanction follow-up

training

field-based support in their own areas of operation for

• baseline survey

• action plan formulation

• action plan execution

• impact assessment

specialised training from time to time

on-going interface support vis a vis government and funding agencies

on-going dissemination of research and training material

on-going awareness generation

The Centre can be visualised as a nucleus, giving rise to many nuclei of empowerment all over the country.

Training

• The training effort of BACPE has been mainly targeted at CAPART partner VOs. It is mandatory, as per the CAPART guidelines for the Watershed Conservation Team (WCT) members of partner VOs to pass the Basic Training Course (BTC) at the SVO with which they are affiliated.

• As many as 2,465 persons have been trained in 88 training programmes, amounting to 25,443 person-days of training since 1998.

• As many as 12 Basic Training Courses have been held at the BACPE so far. 336 Watershed Conservation Team (WCT) members of 116 partner NGOs from 13 states of the country have successfully participated in these 12 BTCs. This amounts to 17,677 person-days of training

• The BTC started off as a 4-week course. Over the years it has grown to be a 2-month programme, largely reflecting feedback from trainees of the earlier courses.

• The structure of the BTC is such as to provide a proper and solid grounding to both technical and non-technical members of the WCT on the principles and practices of participatory watershed development, embracing a whole range of subjects from earthen engineering, hydrogeology, mapping and surveying, PRA, accounts, conflict resolution etc

• Apart from the BTC, several short duration courses are also organized for panchayat members, members of SHGs, government officials, students, village watershed committee members, other NGOs etc. WCT members are also given specialized training in short duration courses.

• In addition to the BTC, at the specific request of the UNDP and the Ministry of Rural Development, GoI, beginning July 2006, special training progammes are being organised on the newly enacted National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). The NREGA represents a historic opportunity to ensure that the Right to Work becomes effective on the ground.

• The aim of these training programmes is to explain the provisions and guidelines of the Act. Simultaneously, they seek to empower trainees to understand the social and technical intricacies of watershed conservation and development which are the main focus of works to be taken up under the NREGA. The idea is that armed with this understanding, these trainers will both help implementing agencies in better implementation of NREGA works and, acting as master trainers, further empower local leadership to do the same. Already 3 such programmes have been organised for carefully selected VOs and CBOs from the states of Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand Gujarat, Rajasthan, Orissa and Karnataka. One programme has also been held for officers of the Bihar government.

Promotion of Watershed Programme

• A total of 18 promotional workshops have been organized by BACPE for CAPART since 1998. These 18 workshops have been attended by 523 participants from 433 NGOs in these 5 states. These NGOs represent 101 districts of these 5 states.

• A typical promotional workshop is of 4 days’ duration. In these 4 days, participants are introduced to the CAPART guidelines, taken on an exposure tour of watershed work done by SPS, taught how to demarcate a watershed on a Survey of India toposheet and intensively explained the CAPART application procedure, the forms to be filled up, eligibility criterion etc.

• SPS has also devised a way of shortlisting prospective CAPART partners through a system of NGO presentations in these workshops, on the basis of which a screening committee especially set up for this purpose assesses the NGO’s capabilities, perspective and vision.

• The promotional efforts of the BACPE have led to an increased penetration and coverage of the CAPART programme in all 4 states.

• It is worth highlighting that since the CAPART guidelines were adopted in 1995 and until 1998 (i.e. for a period of 3 years), there were only 2 partners of the CAPART watershed programme in Madhya Pradesh and Chhatisgarh. After the promotional efforts, at BACPE, this number has gone up to 32 (including SPS0, i.e., a 16-fold increase in the coverage of the programme in these 2 states.

• This is perhaps the highest expansion that CAPART has ever seen in any of its programmes, achieved in the shortest time-frame, while ensuring high standards of quality.

Policy advocacy and training material

• Watershed Reforms: Dr. Mihir Shah was appointed Honorary Adviser to the High-Level Technical Committee set up by the Ministry of Rural Development to review the national watershed guidelines. The contribution of SPS to its landmark report is summarised by the Chairman of the Committee in his Foreword to the report:

"This report would not have been possible without the unstinted support given by Dr. Mihir Shah of Samaj Pragati Sahayog (SPS), who went far beyond his call as Honorary Advisor to the Committee, and willingly assumed onerous responsibility. He has managed to integrate into a flowing and limpid narrative a vast amount of information in the form of submissions and reports that I had gathered from my visits, the research insights gleaned from a decade or more of published academic outputs, besides drawing upon his own vast experience of running similar projects with disadvantaged sections of the tribal community in remote central India. He has synthesized the learning in a way that makes the report eminently readable, and at the same time ensures that it never falls short of requisite standards of erudition. I am sure this report will be used both by practitioners and the academic community with profit. I would like to thank Dr. Mihir Shah and his research team at SPS for an outcome that is characterized by a sense of balance and moderation considering the passions that this programme so easily provokes in many quarters. The report, at the same time, is shot through with a sense of deep commitment and urgency about what is required to be done by policy makers and implementers alike."

• NREGA: At the specific request of the UNDP and the Ministry of Rural Development, GoI, beginning July 2006, special training programmes are being organised on the newly enacted National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). The NREGA represents a historic opportunity to ensure that the Right to Work becomes effective on the ground. The aim of these training programmes is to explain the provisions and guidelines of the Act. Simultaneously, they seek to empower trainees to understand the social and technical intricacies of watershed conservation and development which are the main focus of works to be taken up under the NREGA. The idea is that armed with this understanding, these trainers will both help implementing agencies in better implementation of NREGA works and, acting as master trainers, further empower local leadership to do the same. Already 3 such programmes have been organised for carefully selected VOs and CBOs from the states of Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand Gujarat, Rajasthan, Orissa and Karnataka.

• A key role of the BACPE has been to constantly prepare high quality training material on watershed development. At the specific request of the Ministry of Rural Development, GoI, in 2006, SPS prepared:

o A 308-page fully illustrated training manual on NREGA and Watershed works in Hindi

o A 320-page fully illustrated training manual on NREGA and Watershed works in English

• These manuals were printed with financial support from the UNDP, Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Ford Foundation and Arghyam Trust.

• We have now been requested by the Governments of Bihar and Chhattisgarh to make these manuals available to all their 18,000 Gram Panchayats

• The Ministry of Rural Development has asked us to make training films based on the manuals

• We are also developing e-learning courses based on these manuals in collaboration with the Arghyam Trust

[1] The CAPART SVOs are Hind Swaraj Trust and AFARM (Pune), Development Support Centre (Ahmedabad), People's Science Institute (Dehradun), Agragamee (Orissa), Peermade Development Society (Kerala) and Samaj Pragati Sahayog (Madhya Pradesh). Organizations like WOTR which have developed a systematic and graduated approach called “Participatory Operational Pedagogy” (POP) as well as the “Mother NGO” concept and MYRADA, also have an outstanding record in capacity building for watershed development and could play a vital role as national SVOs.

[2] This is how we must visualise the NGO effort -- not as a substitute for government initiative but as a stimulus for improving its quality.

/articles/baba-amte-centre-peoples-empowerment-case-study-support-voluntary-organisation