1. The Kamla River

The Kamla is a famous river in the Mithila region of Bihar. The harrowing tales of destruction that are associated with the most unsettled river of Bihar, the Kosi, are not linked to the Kamla. The waters of the Kosi is said to carry far less nutrients as far as agriculture is concerned but the Kamla enjoys a far better reputation among farmers for the nutrients that are present in its waters. It is said that the land that forms part of the Kamla basin is so productive that it is equated to producing gold. A kattha (slightly more than 3 decimals) of land here easily yields 80 kilograms of paddy and the only precondition is that the Kamla should be helpful. However, despite being such a life saving river, the Kamla does not find much of a mention in the scriptures. Even in Ramayana or the Mahabharata, there is no reference of the river that could establish the importance of the Kamla. A similar lack of mention becomes obvious within the Jain and the Buddhist literature too. However, the Kamla is very popular when it comes to the folk tales and legends and its good reputation overtakes that of the Kosi River. The local folklore regards the Kamla as a virgin Brahmin deity.

It is said that long ago the Kamla used to live in the heavens when Brahma, the creator of the world decided to start life on earth. He assigned the roles of the deities and fixed the Brahmin priests who will perform their rituals. Some how, the Kamla was missing when Brahma finalized the list. When she came to know of it, she went to Brahma and complained about the omission. By that time there was no Brahmin left who could be given charge of performing the Puja of the Kamla. Brahma then told the Kamla that she is the deity of water and will be worshipped by the fishermen. A son will be born to the King Vishwambhar Sardar and his wife. Rani Gajawanti and this child would initiate the worshipping of the Kamla. As the legend goes. Vishwambhar Sardar was a resident of the village Bharora near Singhwara, northwest of Darbhanga, in Bihar. When Brahma told the Kamla about who her priest would be, the child (who would be the priest) was already in his mother's womb and that aroused the curiosity in the Kamla. The Kamla shadowed the child, named Garbhi Dayal Singh, looked after him, nursed him and protected him like her own child. The story of this child, from his birth to growing into youth, and his marriage forms a legend and sung by the local folk singers who take weeks to narrate the entire episode. This boy was married to a girl named Dhani and born to Dukh Haran Sardar and his wife Bahura from Bakhari, in Begusarai district. Bahura was a witch and she tortured Vishwambhar Dayal and his son Garbhi along with his family but the Kamla protected him like a shadow.

After cutting Bahura to size, Garbhi returned home with his wife. Dhani, and performed the first puja of the Kamla on the banks of Tilyuga. It is since then that the fishermen of the area started worshipping the Kamla. Similar stories are doing the rounds is linked with the Kamla and the ruling deity of the fishermen, Jaisingh.

Another story that is prevalent in the folklore is that the Kamla has a fisherman well-wisher named Koilabir. He has a spade that has a handle of eighty-four maunds with a blade that weighs eighty maunds. Koilabir paves the way for the Kamla with the help of this spade and the Kamla follows him. He is very strong and stout and protects the Kamla from any untoward incident. As the legend goes, once a very rich and powerful person named Ugla, a dealer of hides and bones got envious of the Kamla as she is worshipped by all and sundry and no one cares about him. He thought of teaching the Kamla a lesson and put a bundh across her with a view that when Kamla would rise. he would pull her out, take her to his home, put vermilion powder on her forehead and marry her. The Kamla got scared after listening to the resolve of Ugla and went to Koilabir to tell him the story and seek his help. Koilabir, having listened to the Kamla, went and demolished the bundh and the Kamla remained free.

Ugla, however, was not prepared to swallow the defeat so easily. He put a bundh of bones across the Kamla who went to Koilabir for help, once again. Koilabir returned to the bundh site and found that it was built of bones and he refused to touch or break the bundh, being built of an unholy material. He, however, advised the Kamla to go to Delhi and meet one Maharaja Amar Singh who might set her free from the bondage by breaking the bundh built of bones. He told the Kamla that the Maharaja was a celibate and had a seven-storied palace and a sandal tree was located south of his palace. The Maharaja had a wrestling ground that was 22 kilometers wide and that she would not find any difficulty in locating the place. Kamla went to Delhi and traversed the wrestling ground and climbed the sandal tree. -After sometime, a hefty person arrived at the scene. Smelling some mischief, he shouted, ...I have lost my energy. It seems, some woman has traversed this wrestling ground. If I find her, I will give a punch on her face and bury her eighty feet below the ground. The Kamla descended from the tree thinking that the person could be none other than Maharaja Amar Singh and that he would surely protect her by going to Morang where Ugla had put the bundh across her. She told all her problems to the Maharaja as to how Ugla had intercepted her and was chasing her with vermilion powder in his hand. She asked him for help. Amar Singh assured her all the help and said that he would be consigned to hell if he could not bail her out of the trouble.

The Maharaja had a massive physical frame having a height of 9 yards and his chest measuring 6 yards across. To accomplish his task he was quick, to go to his mother for her blessings. Amar Singh returned to follow the Kamla to the place where the bundh was constructed. He killed Ugla but when he saw the bundh built of bones, he; too: refused to break it but advised the Kamla to go further west and look for Miran Faquir who would free her. The Kamla went to Arabia, in the west, to look for Miran (or Mira or Mir Saheb), a Muslim, and sought his help. Miran came and broke the bundh and freed the Kamla from the clutches of Ugla. The Kamla remained free ever since. The local fishermen worship the Kamla and; along with her, Miran Faquir also gets the devotees offerings.

It is difficult to say what kind of truth lies behind these folk tales but it is certain that the rivers are a part of our society, culture and civilization and it would be a mistake to judge them merely as drainage channels. A temple in the name of the Kamla is being built near Partapur on the eastern bank of the Kamla, close to Jhanjharpur in the Madhubani district. An annual fair revering the Kamla is also held here regularly.

2. Geographical Features of the Kamla

The River originates from the Mahabharat range in the Himalayas, close to Sindhulia Garhi at a height of 1200 meters, in Nepal. Many rivulets, like the Jima Khola, the Chandaha, the Thakua Khola, the Tawa Khola, the Baijnath Khola, and the Kali Khola join the Kamla before it disgorges into the plains near Tetaria, close to Chisapani, in Nepal. The catchment area of the river at Chisapani is only 1409 sq. km. A dam on the river is proposed at this location. The river then flows in the southerly direction and is joined by the Jiwa (Baiti), the Ghurmi, the Lohjara and the Mainawati on its left bank. No river joins the Kamla on its right bank till it crosses into India but a stream, the Bachhraja, branches off from the river. The Bachhraja was, once upon a time, the main channel of the Kamla (Fig. -2).

The Kamla enters India, about 3.5 kilometers north of Jainagar, in the Madhubani district. In the Indian portion of the Kamla, the rivers like the Dhauri, the Soni, the Balan, the Gobarjai, the Trishula and the Sugarwe join it on its left bank. Of these rivers, the Balan comes from the Himalayas and flows east of Ladania Thana and is joined by another river called the Soni. This river joins the Balan near Pipra Ghat in the Babu Barhi block of Madhubani district and the resulting stream is called the Kamla-Balan. There was a very severe flood, in Bihar, in the year 1954 when the Kamla turned eastwards and joined the course of the Balan near Pipra Ghat. This combined stream joins the Kareh, southeast of Badla Ghat. The flow path of the Balan, which is also called the Jhanjharpur Balan, is the path that the Kamla has adopted these days. The river passes through the villages of Bhatgawan, Bithauni, Chapahi. Gangdwar, Imadpatti, Kandarpi Ghat, Gandharayan. Bhabhan, Banaur, Harna, Mahrail, Ojhaul, Bahl, Mehath and Mahinathpur before it reaches Jhanjharpur ;.kihere it crosses the Darbhanga-Nirmali rail line. South of this railway line, the Kamla-Balan passes through the villages of Balbhadrapur, BeIhi, Khairi, Phatki, Prasad, Bhit Bhagwanpur, Bauram, Jhamta and Jamalpur before it joins the Kareh near Phuhia. The Balan used to join the Tilyuga near Rasiyari, in earlier days. But the changing courses of almost all the rivers along with the embankments built on the rivers to prevent this shift, have changed the entire drainage mechanism of the area. Many rivers have ceased to exist while many others have their profiles grossly changed. The Tilyuga and the Bainti rivers are now lost within the Kosi embankments.

The Kamla enters India, about 3.5 kilometers north of Jainagar, in the Madhubani district. In the Indian portion of the Kamla, the rivers like the Dhauri, the Soni, the Balan, the Gobarjai, the Trishula and the Sugarwe join it on its left bank. Of these rivers, the Balan comes from the Himalayas and flows east of Ladania Thana and is joined by another river called the Soni. This river joins the Balan near Pipra Ghat in the Babu Barhi block of Madhubani district and the resulting stream is called the Kamla-Balan. There was a very severe flood, in Bihar, in the year 1954 when the Kamla turned eastwards and joined the course of the Balan near Pipra Ghat. This combined stream joins the Kareh, southeast of Badla Ghat. The flow path of the Balan, which is also called the Jhanjharpur Balan, is the path that the Kamla has adopted these days. The river passes through the villages of Bhatgawan, Bithauni, Chapahi. Gangdwar, Imadpatti, Kandarpi Ghat, Gandharayan. Bhabhan, Banaur, Harna, Mahrail, Ojhaul, Bahl, Mehath and Mahinathpur before it reaches Jhanjharpur ;.kihere it crosses the Darbhanga-Nirmali rail line. South of this railway line, the Kamla-Balan passes through the villages of Balbhadrapur, BeIhi, Khairi, Phatki, Prasad, Bhit Bhagwanpur, Bauram, Jhamta and Jamalpur before it joins the Kareh near Phuhia. The Balan used to join the Tilyuga near Rasiyari, in earlier days. But the changing courses of almost all the rivers along with the embankments built on the rivers to prevent this shift, have changed the entire drainage mechanism of the area. Many rivers have ceased to exist while many others have their profiles grossly changed. The Tilyuga and the Bainti rivers are now lost within the Kosi embankments.The Kamla also brings a huge amount of detritus along with its flow although it is not as much as it is in the Kosi. The Kamla also changes its course from time to time. Many of its abandoned channels become active during the rainy season and can be seen on the western side of the present stream of the Kamla-Balan. These abandoned channels are spread from Benipatti to Rampatti in the north to the outskirts of Darbhanga and up to 35 kilometer further down near Jhanjharpur, in the south. The total length of the Kamla-Balan is 328 kilometers of which 208 kilometers lies in Nepal and the remaining 120 kilometers is in India. Chisapani, where the river disgorges into the plains, is located 48 kilometers north of Jainagar.

The total catchment area of the Kamla-Balan is 7232 sq.km. of which 4488 sq.km. is located in Bihar and the remaining portion is in Nepal. Within India, 63 percent of the catchment area lies in Madhubani district, 31 percent in Darbhanga district, 3 percent each in Saharsa and Samastipur districts and only one percent in Khagaria district. The river remains in spate in the rainy season and can be forded in the rest of the year. The maximum rainfall in the Indian Territory of the Kamla basin is 1450 mm in the Khutauna block of the basin and the lowest is in Kusheshwar Asthan (1000 mm). It is an amazing fact that despite having the lowest rainfall in its part of the basin, Kusheshwar Asthan remains submerged for a major portion of the year. We shall go into the causes of such submergence later. The Kosi on the east, the Adhwara on the west, and the Himalayas on the north and the Kareh on the south surround the Kamla-Balan basin. The total population of the Kamla-Balan basin (1991 census figures) was 38.72 lakh, and which was likely to have gone up to 44.64 lakh in 2001.

3. Different Courses of the Kamla

The Kamla although, it is not as unstable as the Kosi but it is known to have shifted its course and ever since such records are being kept, four different channels of the river are known to have existed. The Project Report of the Kamla Embanking Scheme (1956) mentions about the different courses of the river and a brief description of these channels of the Kamla.

3.1. The Bachhraja Dhar

At the time of the Rennels survey (1779), the Kamla used to flow very close to the west of Jainagar. It was also flowing west of Madhubani but in Darbhanga, the river was passing three kilometers east of the town and used to join the Kareh near Phuhia via Ghausaghat and Trimuhanighat. The total length of the channel was 240 kilometers. After the Rennel’s survey, the Kamla followed its old course till the village Rathos but it took a turn near Raghauli to join the Darbhanga Bagmati, east of Kamtaul railway station. It then proceeded to join the Kareh, upstream of Hayaghat railway station. The total length of this route of the Kamla, from Nepal hills to its confluence with Kareh, was only 158 kilometers and this stream marked the extreme western boundary of the Kamla.

3.2 The Pat Ghat Kamla

This channel of the Kamla, starting from the east of Jainagar, followed the Jainagar-Sakri rail route up to Rajnagar railway station and then it took a turn towards south to cross the Sakri-Nirmali railway line, west of Lohna Road railway station. The Kamla then joined the Tilyuga near Baltharawa village and this 189 kilometers long route of the river was known as the Pat Ghat Kamla.

3.3 The Sakri Kamla

The Pat Ghat Kamla, too, never remained in its place and, in 1922. it flowed from Jainagar to Rajnagar and crossed the Sakri-Jainagar rail line at Rajnagar itself through the bridge no: 16A. Then the river took a turn to the bridge no: 15 and, ultimately, returned to its old channel after passing through the bridge no: 7. The river crossed the Darbhanga-Nirmali rail line through bridge no: 54, west of Sakri railway station. The Kamla now started flowing parallel to, and east of. the Sakri-Behera-Supaul road and joined the Jiwachh Dhar near Jhamta. Still ahead, this new channel joined the Pat Ghat Kamla channel near Saharawa and proceeded to join the Tilyuga near Baltharwa. The total length of this route in the terai and the plains was 211 kilometers.

3.4 The Jiwachh Kamla

The Kamla changed its route once again, in 1930, near Mohanpur village. This new channel crossed the Sakri-Jainagar rail line through bridge no: 9 and adopted the path of the Chhatahari Dhar. This channel used to flow through Badriban and Kakana villages and flowing further down south and used to join the Jiwachh near Nima. This channel of the Jiwachh crosses the Darbhanga-Nirmali rail line through bridge no: 43 and, joins the Sakri Kamla near Jhamta and the Tilyuga near Baltharwa. The total length of this route is 234 kilometers. During 1939-1940, there was another change in the Chhutahari Dhar-Jiwachh Dhar route and the stream between Badriban and Dhanuki started flowing through Sahura and Akaspur and rewound near Dhanuki to follow its old route. The Kamla followed this channel till 1954 when it suddenly took a turn near Bhakua to join the Balan near Pipra Ghat.

In the lower reaches, the Kamla-Balan bifurcates near the village Gulma. The major channel that flows towards the east is called the Kosi Dhar by the local people and crosses the Mansi-Supaul rail line near Dhamara Ghat railway station and ultimately joins the Kareh. The southern channel of the Kamla-Balan is called the Bahwa Dhar and it joins the Kareh below Phuhia, two kilometers downstream of Tilkeshwar.

4. The Floods of the Kamla

Few years after the British colonization of India, a severe famine struck the country in 1770 and its impact was also felt in Darbhanga. Those days what was known as Darbhanga comprised of the present Darbhanga, Madhubani and Samastipur districts. On the one hand there was the adverse impact of the famine and, on the other, there was the terror of the zamindars. The agriculture in the area reached its lowest ebb because of this combination. At one stage, in 1783, the collector of Darbhanga had to propose that the Vazir of Oudh should be requested to send peasants so that agricultural operations could be resumed in the area. Towards the end of the eighteenth century Pargana Pachhi and Allapur of Darbhanga was a sanctuary of wild animals. The situation changed slowly and according to a report of the collector of Darbhanga (1828), there was more fallow land than the cultivated one. The situation was so bad in the terai area, close to Nepal and the area enclosed between the Dhaus and the Tilyuga, that for every bigha of cultivated land, at least, fifty bighas of land remained fallow. Some improvements were recorded in the early nineteenth century but till then half the land in the district was lying fallow and in the northern portion the uncultivated land was even more. By 1840, cultivation was started on three quarters of the land in the district but, in the northern zones, it remained only half the land was cultivated and, in general, agriculture stagnated for a long time to come. In 1875, the land under agriculture touched a figure of 79 percent and according to the survey settlement report of 1896-1903, agriculture was practiced on 80 percent of the land in Darbhanga. ...We should probably therefore be justified in concluding that cultivation has nearly doubled itself in the last hundred years, but that the greater part of the increase took place in the first half of the last century.

Famine was an improbability in the area of Darbhanga as it was cris-crossed with large number of rivers and streams. The land in Darbhanga was then infested with the jungles of Kans (Thatch Grass-Saccharum), Pater (Spotneum-Typha-Australis) and was waterlogged and marshy. ... The largest uncultivated area is in the headquarters sub-division, where there is considerable amount of swamp and marsh, which is under water for the greater part of the year. It is nearly as great in the Madhubani subdivision where there is much culturable jungle along the banks of the streams and on the Nepal frontier: and it amounts to 23 percent of the total area of the Madhubani than a where it is due to the large number of mango groves which strew the country.

O'Malley (1907) was of the opinion that further expansion of agriculture in the district was not possible and that there were ample evidences to shows that soon the production from the land here would not be able to sustain the pressure of an increasing population. In which case either the standard of living of the people will go down or the productivity of the land will have to be raised. The population of Darbhanga, in 1901, was 29,12,611 which now (2001 census) stands at 1,02,69,537 (inclusive of Madhubani and Samastipur).

Thus, two conditions for the development of Darbhanga were already set in the beginning of the twentieth century itself that, should the population rise further, the standard of living would decline and the land of Darbhanga could not sustain the needs of its population unless productivity is raised. To increase the agricultural production, it was essential that more and more land was brought under cultivation. This was possible but there was a limit to its expansion and it was essential that the drought and floods are brought under control and adequate irrigation is provided for the agriculture production to rise. The flood situation was such that the area was surrounded with rivers from all sides. While the rivers like the Tilyuga, the Balan, the Bhutahi Balan, the Panchi, the Dhokra, the Bihul, the Kharag, the Ghordah, the Sugarwe, the Supain, the Baiti, the Soni, and the Kamla were flowing from north to south; there was a pressure from the Adhwara Group of rivers and the Bagmati from the west and southwest. There was an impact of the Burhi Gandak and the Ganga in the south while the Kosi was knocking at the door from the east in the form of the Dhemura. And to cap it all, most of these rivers were unstable. We have had a glimpse of the changing courses of the Kamla but the other rivers also were no different either. The Kosi, however, was notorious for its vagaries. The silt content of the water in these rivers had its own set of problems. A river, when it descends down the hills, has a tremendous velocity of flow, which reduces drastically as the river reaches the plains. This allows the sediments contained in the flow to spread and settle over a large area. In the following monsoon season, the river cuts across the deposited sediments and carves a new path for itself. That is how the rivers make their delta. Shallow beds of the rivers and flat gradient of the land in plains create situations that if it rains well even for a day, all the rivers would overflow their banks and flood the area and as one moves in the south easterly direction, the spread of water was on the rise because all the rivers were converging in that direction only.

Apart from this many rivers were embanked by the zamindars who had also put ring bundhs around habitations to protect them from floods. These structures used to impede the drainage and were instrumental in making the floods permanent in the form of waterlogging.. ... Owing to this combination of circumstances, the district has always been subject to severe and widespread inundations, which cause a good deal of temporary suffering. But, as a rule, the distress they cause soon passes away; the dwelling which are destroyed are quickly replaced, as the cost of erecting such mud-walls huts is small; and the cultivators are compensated, in large measure, for the losses they sustain by the fertilizing silt left by the receding waters, which increases the productiveness of the soil and ensures rich crops.

Detailed accounts of earlier floods are available in old British documents, gazetteers, settlement and administrative reports and the annual reports of the Irrigation Department. For example, there were three successive floods in 1893, in the months of July, August and September. The first flood of July was absorbed but the following floods came when the ground and the available cushion for the flood was saturated. On one side, the Muzaffarpur-Barauni-Katihar railway line was blocking the passage of the drainage of the Burhi Gandak and the Bagmati, on the other side, the Kamla was maintaining the pressure from the north. This resulted in the passage of one-meter deep water from northwest to southeast through the district causing immense damage to crops, dwellings, roads and the railway lines. Almost half the district became an island and the people were forced to take shelter on the high lands, railway lines and the roads. .... Fortunately, the waters rose gradually; no lives, so far as could be ascertained, were lost; and the people had time to save their stores and to drive off most of their cattle. . .The way in which the people recovered from their losses, instead of being overwhelmed by them, was very remarkable.

Similarly, the floods of 1898 in Darbhanga were caused by the rising levels of the Kamla, the Kareh, the Darbhanga Bagmati and the Burhi Gandak. Many of the thanas, from Beni Patti, in the northwest, to Darbhanga, Laheria Sarai, Dalsing Sarai and Waris Nagar, in the southeast, were hit by this flood. Spills from the Baraila Chaur inundated Dalsing Sarai. Although, there was no loss to cattle, this flood took away some 164 lives with it besides destroying 88,000 houses. On the positive side, there was a bumper Rabi harvest that year because of fresh soil on the fields. If any body needed some employment, it was available in the repairs of the Barauni-Katihar railway line and not a single application was given for loans from the government...Prices did not rise and the Collector reported that, taking the district as a whole, the flood was rather beneficial than otherwise.

Flood came in 1902 also but the flood of 1906 created a history in Darbhanga. The common belief is that a flood is never succeeded by a famine but this years, apart from demolishing many a bridges, roads and rail lines, demolished this belief too. The first wave of flood came in the month of July and it was followed by incessant rains that started 6th August and continued up to the 24th August submerging the greater part of the district for over 16 days. From the Kamla in the north to the Burhi Gandak in the west with a simultaneous rise of the Bagmati and the Darbhanga Bagmati, most of the district was inundated. Almost entire Darbhanga town was under a sheet of water excepting the kachahri, in Laheriasarai, and the Bara Bazar in Darbhanga and many people rendered homeless took shelter on these highlands. Floodwater entered the town so suddenly and the onset of flooding was so fast that the people did not find time to react to the situation and had to move immediately. It took about a week for the water to recede in the town but, in other areas, it took over two months. The damage to the crops was so extensive that the prices soared high. The year (1905-06) was also not a very good year, generally, as far as agriculture was concerned. The floods and the rising prices broke the backbone of the people. Famine had to be declared in Rosera and Behera and free rations had to be distributed to 45,000 flood victims in the month of October, 19,000 in the month of November and 15,800 in the month of December. If the local officers and the indigo planters had not distributed food, a near starvation situation would have occurred. Test relief works had to be opened despite floods and, at one point of time, some 32,000 persons were engaged in the relief works. This worst ever flood till date in Darbhanga had water spread over 2,714 sq. km in the Sadar subdivision, 1510 sq. km. in Madhubani and 1075 sq.km. in Samastipur subdivision bringing the total to 5299 sq. kilometers.

Floods were also faced in Darbhanga in 1910, 1912, 1913, 1915, 1916, 1919, 1920 to 1922, 1924, 1926 to 1943, 1946, 1953 to 1958, 1960, 1962, 1963, 1965, 1968, 1971, 1975, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986 to 1988, 1990, 1993, 1995 to 2000, 2002 and 2004. Of these, the floods of 1954 and 1987 were the most severe floods of the last century. The flood of 1954 is important in the sense that virtually nothing was done to protect people from the floods till then because whatever was done in the independent India to tame the rivers and their floods was subsequent to the adoption of the flood policy of 1954. Prior to that date, all the works on the flood control were done by the farmers and the zamindars and the local people. The engineers believe that these works were undertaken for immediate and local gains and were thoroughly unscientific in nature.

In that context we shall glance through the problems faced by the people in 1954. in the Kamla Basin, in Darbhanga as that formed the basis of all the future flood control works in the district.

Till the beginning of rainy season, in 1954, the Kamla was flowing in the Jiwachh Dhar at the Kumhar Tola village, slightly north of Raiyam. This was the route of the river since 1930. It used to stray a bit here and there during the rainy season but there was no major change in its direction of flow. Despite following a given path, the river spared no opportunity of overflowing its banks and inundating the surrounding area. Because of its excessive sediment load, the Kamla had rendered the beds of the Jiwachh and the Lalbega shallow. The Lalbega was a small stream, which used to Join the Jiwachh, one and half kilometer below Kumhar Tola. The Jiwachh and the Lalbega had very limited waterway and the situation became worse when the water of the Kamla started pouring into them to the detriment of the western portion of the Madhubani town. This entire flow of the rivers used to wander in the lower - areas and, it appeared that, the river was making its delta near Raiyam. Looking at the rivers, it was difficult to identify the streams or to predict which one would emerge as the final route of the river. At times, excessive flow was seen in one channel while immediately thereafter, it used to get dry with sand appearing in its bed. It appeared once that the Kamla will adopt its Ghausa Ghat course but in the month of October, it took a sudden turn near Bhakua and joined the Balan, abandoning the Ghausa Ghat channel filling it with sand.

The floods came twice this year in the month of July and once in the month of August. It ruined the Kamla Canal System and the embankments being built near Jainagar on the Kamla, in the first instance, and the west flowing waters of the river did not spare even the Jainagar-Janakpur railway line. The river also appeared to have carved a new course for itself, on the left bank, near the village Bairaha and a similar incident took place near Khairamath, where the river was eroding the banks very badly. Most of the houses in this village were washed away. The south flowing waters of the Kamla devastated the villages of Tehra, Seira and Hanuman Nagar and damaged Belahi, to a great extent. All this water got into the Dhauri near Chatra. Simultaneous erosion was going on near Bhakua and the water of the river was spreading towards the east. In the second wave of the floods, in the month of August, Balua Tol was washed away and the Kamla was now inching towards the Soni. By October, the river joined the Balan near Pipra Ghat.

The Balan did not have the capacity to hold the waters of the Dhauri, the Soni and the Kamla. The result was that heavy flooding took place all along its course. This water extended from the Pat Ghat Kamla, in the west, to a 3 to 6 kilometers strip along Tamuria, in the east. The entire area between Bhaduar Ghat to the Sakri Nirmali rail line appeared like an ocean. On the other side, the floodwaters of the Kamla had filled the Mangrauni Chaur, west of Madhubani, in the first flood in the month of July itself, with water depths varying from 2 to 2.25 meters, widespread damage of crops and dwellings was observed in Raiyam. Because of the floods and sand casting of the beds of the Jiwachh and the Lalbega: in the month of August, the water of the Mangrauni Chaur found it hard to get drained out and; as a result, got choked with sand of up to 2 meters depth. The Kamla waters overtopped the railway line near Manigachhi and also north of Madhubani. The train services remained suspended for over nine days.

The worst ever flood till date in Darbhanga, was spread over 65 percent of the total area of the district. Crops were lost almost in the same proportion. Out of a total of 3,438 villages of Darbhanga, 2,501 villages were affected by this years flood. A population of 19,76,771, out of the total population of 37,67,798, was affected in Darbhanga by the flood that destroyed 32,950 houses and killed 13 persons besides killing over 500 cattle.

In 1955, almost a similar story was repeated in Darbhanga. The waters of the Kamla and the Balan reached up to the Deep village, west of Tamuria while on the right bank, its spread extended up to the Pat Ghat Kamla. The railway line between Jainagar and Khajouli was overtopped this year also and the train services had to be suspended for some days. The water also overtopped near Tamuria railway station and the train services had to be suspended north of Ghoghardiha. The floods had affected 2341 villages, 25.02 lakh people, and 4.16 lakh hectares of land in Darbhanga besides killing 17 persons. More people suffered from floods this year than in the last year.

5. Irrigation Problem in the Kamla Basin

A major portion of the Kamla in the Indian territory now lies in the Madhubani district that earlier used to be a subdivision of what was earlier Darbhanga. Old British records reveal that irrigation was neither needed nor practiced in Darbhanga and the Samastipur subdivision of Darbhanga. The small rivers originating in Nepal, acquire a big shape when they enter Madhubani and it was generally not possible for the farmers and the zamindars (Land-Lords) to tamper with these rivers. Also, the spread of the floodwater was so vast and wide that not only the requirement of the monsoon paddy was met with: the moisture retained in the soil was enough to meet the needs of the Rabi crop also. The extent, duration and the depth of floods were, generally; known to everybody and the farmers had with them the varieties of paddy seeds to suit every given condition. The situation in Madhubani was a bit different and irrigation was needed there in the Rabi season and, it is for this reason, there existed a very efficient and well thought out irrigation system with the help of pynes and tanks. There are people who still survive to tell about the indigenous system of irrigation but the wisdom is dying slowly and within years all these people will be no more with us. It must be mentioned here that the people had their own system of farming, used their owns seeds, and an irrigation system that did not consume as much water as one needs today for the high yielding crops.

This entire area was cris-crossed with small and big rivers mentioned earlier. Many small streams, that were almost perennial, completed the landscape. The small size of the nallahs used to help the farmers in that they could block and divert it at their will and take the water to their fields. Such streams are called pynes locally. A small input from the zamindar used to be a big help in utilizing this resource.

There used to be an engineer and sub-manager named R.S.King with the Raj Darbhanga who had become an expert on making use of these pynes for irrigation. The First Irrigation Commission of India (1903) has lauded the efforts of King in the Madhubani district. It so happened that the Government prepared a scheme, in 1877, for constructing a 19 kilometers long canal, taking off from the Kamla, to irrigate 21,300 hectares of land in Madhubani. This scheme was to cost Rs. 10,41,000/-. The government was in a dilemma whether to take up the scheme or not, for the British Government those days used to take up only such schemes that would bear their own expenses, pay the interest on the capital and yield some profit to them. The British were also vary of constructing anything close to the Nepal border for they feared that if the Government of Nepal constructed any dam or a bundh upstream in their territory the Indian project would fail automatically. These were the reasons that the 1877 scheme on the Kamla was not taken up for construction.

When the members of the first Irrigation Commission of India (1903) reached Darbhanga in 1902, they happened to meet R.S.King who told them that it was definitely possible to irrigate the area that the Government wanted to. But the fact was that, in a normal monsoon year, the farmers would not take water from the canal because they would not need it and, in a deficient rainfall year, there would not be enough water in the canals for the farmers to irrigate their fields. The Government would not get any revenue in either case and that would mean that the Government would be a loser. The Government, however, believed that the quantity of water in the canals would never go so low that there will not be any water available in them to irrigate the fields in a scarcity year like 1888-89, 1891-92, 1896-97 or 1901-02. The Commission suggested further studies of the proposed project because its cost was so low and the risks on the returns even lesser.

The Commission was very pleasantly surprised that under the enlightened orders of the Darbhanga Maharaja private irrigation works were taken up on a large scale with R.S King providing the technical input. In the unprecedented drought of 1896-97, R.S. King put temporary bundhs across the Kamla and diverted its waters to the old and abandoned channels of the river, in the east; from where the farmers took the waters to their fields with the help of pynes or the village channels. In this way he saved 9000 hectares of paddy at a cost of just Rs. 10,000/-. In May 1901, he added 3 kilometers more to the canal and saved paddy crops worth 14,250 hectares belonging to 42 villages. In the same year, he diverted the entire flow of the Kamla into the old bed of Jiwachh by putting an earthen dam across the river and secured a good Rabi harvest. This entire fete was achieved just at a cost of Rs.4,000/-.

INTERVIEW WITH R. S. KING Q. How many bighas or acres do you consider that you irrigated by these means? - It is shown in brief here (map). 40,000 acres of yellow: that is the crop secured. 5000 rabi irrigated after it had been sown and 15,000 of these villages (shown in map) which had water given to them in their tanks for their cattle and for their seedlings.

Q. Then 45,000 acres were really irrigated? - Yes. Q. So this irrigation quite doubled the value of the out turn? - More than that. It would be multiplied by four. Q. And the outlay altogether was how much? - Including the channel made in 1897, it was between Rs. 13,000 Rs.14,000. Q. Did you first make these channels in 1897? - I made this channel (indicates on map Narkatia) in 1897 and also this one here (indicates on the map Arerh ). I spent Rs. 10,000 in 1897 and Rs. 4,000 last year. Q. It was a successful enterprise. I think? - It was only done bit by bit from practical experience of how the water had been flowing for years with the help of natives.

Source: Report of the First Irrigation Commission. 1903. page 216. Interview on 30 October 1902. |

The interesting fact was that the Government had -set aside Rs.71, 000/- for relief operations in Darbhanga, in 1901-02. to meet any scarcity. But just as everything was near normal in the Raj, the relief operations had not to be taken up. The Irrigation Commission (1903) writes that, ...had this money been expended in the way which we Fcue advocated and with the same happy results as have been attained by Mr. King irrigation might have been provided for between 61,000 and 80,000 hectares of winter rice. King was very ably supported by his colleague Sealy, in his venture.

The First Irrigation Commission, while lauding the efforts of King lamented that such kind of works cannot be taken up by the Public Works Department (irrigation was the responsibility of the PWD those days-Author). It felt that the manager of private estates had a much freer hand in undertaking measures for the benefit of his tenants than can be given by the PWD. If the Government had to build canals, it would be expected to pay a high compensation for all the land occupied, provide crossings at all the village roads and to incur charges and liabilities which were really prohibitive in case of works required to meet temporary emergencies. Above all, a direct return of some kind was expected on the outlay, which involved the introduction of a scale of charges, and consequent inquisitorial measures, which were certain to be unpopular, and costly.

King only performed the duty of a responsible engineer but did not work wonders. Madhubani is interspersed with various small and big streams and there has been a rich tradition of irrigation with the help of these dhars, as they are called locally. King achieved results by combining the experience of the farmers about the direction and the magnitude of the flows, his technical competence and devotion to the profession and the resources of the Darbhanga Raj. Until recently, the farmers of Depura village, near Benipatti, used to intercept the waters of the Bachhraja and divert it to Benipatti chaur (Land depression formed, generally, because of shifting of the river bed) through the Hajma Nalla that passed through the villages of Depura. Nadaut and Muhammadpur. From the Benipatti Chaur, the water used to be tapped for Rabi irrigation by the villagers of Depura, Nadaut, Muhammadpur, Bhatahiser, Benipatti, Pauam, Birauli, Adhwari and Salaha. This was the traditional source of water and the traditional technology for irrigation in these villages. Within Benipatti, a nalla takes off from the eastern bank of the Bachhraja dhar, north of Chamma Tol. Its waters fall into the Navaki Pokhara (Benipatti) and re-emerges through Dhobghat Pulia. This nalla irrigates the fields in Baraha, Kataiya, Bankatta, Damodarpur and Ballia. Similarly, the nallah that emerges from the west bank of the Bachhraja Dhar joins the Sansar Pokhara. This feeds another nallah that passes through Sarisab, Benipatti, Behta, Jagat and Jagat Araji and finally falls in the Soilee Dhar irrigating all the fields on its way.

The residents of the Partapur village, near Jhanjharpur, had befriended the Bolan River and tap its waters for round the year irrigation. This is detailed elsewhere. The entire area of Madhubani district has some story of irrigation or the other, which no engineer. other than King, ever bothered to understand or examinees.

Upon the recommendation of the First Irrigation Commission, an irrigation scheme designed by Sibold was proposed for implementation, in 1906.The idea was to renovate the canals that King had made in 1901. According to Darbhanga Gazetteer (1964), a scheme to irrigate 12,000 hectares of land was prepared in 1901 at an estimated cost of Rs. 50,000/-. This scheme, too, did not work. There seems to be some confusion here because the Commission had praised the efforts of King and King himself, in the interview given to the Commission, had said that he had successfully irrigated 18,210 hectares of land. This canal unfortunately did not function well and was abandoned. Renovating the same canal with which King had irrigated 18,210 hectares of land should, normally, not have failed.

However, there was complete silence over the issue of irrigation from the Kamla till 1950. This year, an attempt was made by resurrect King Canal by cutting it in a width of 3 meters but the canals got heavily sand cast. The Bachhraja Dhar had no regular source of supply of water and hence after the rainy season was over, the Dhar as well as the canal got dried up.

In 1951, as a relief measure, the Bachhraja Dhar was re-sectioned once again. Jawahar Lal Nehru had laid the foundation of this work in the Narkatia village. The farmers in this village still fondly remember the visit of Nehru and that of Indira Gandhi. A good coverage of irrigation was achieved in the Kharif season this year but, in the Rabi season, the irrigated area was limited to 900 hectares. In 1954, a fresh-scheme to irrigate 15,150 hectares of land in the basin was proposed. The problem was that the channel of the river at Jainagar, where the headwork was proposed, was not stable. Being located closer to the foothill, this place was a storehouse of sand and silt and the river used to change its course because of this sediment load. The changing course of the river would desert the head-work every year and a new pilot channel would have to be dug to feed the canal.. Sometimes, the rainwater gushing from Nepal used to destroy the canals. Then, the arrangements to protect the canals from the attack of water coming from upstream had to be taken up and head-works had to be constructed. The irrigation, however, never improved. Against the expected irrigation of 15,150 hectares, the actual achievement in 1959-60, 1960-61, and 1961-62 was only 460 hectares, 600 hectares and 875 hectares respectively. There was a proposal to construct a weir on the Kamla at Jainagar to regulate the flow of the river and the construction of this weir had started in 1959 and it was hoped that there would be no problem after this weir becomes functional.

This scheme started providing irrigation in 1964.

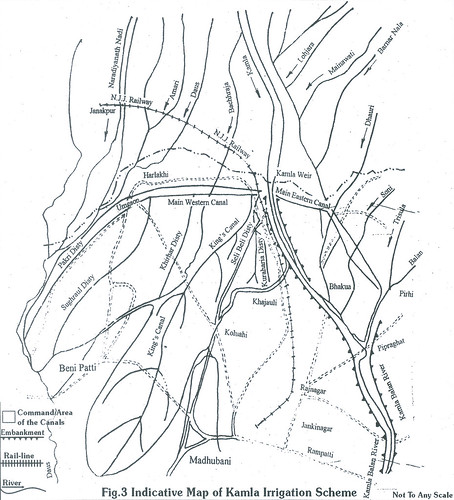

6. The Kamla Irrigation Scheme

An irrigation system was planned with the extension of canals in the Kamla Project, in early 1950s, and the Kings canals were later merged with this system. A weir was constructed on the Kamla near Jainagar to divert water into the canals and it was anticipated that all the problems related to the irrigation would be solved. Unfortunately, this did not happen.

The problem with this area of Madhubani is that there is enough water during the rainy season and additional inputs are not required, generally. Sometimes, deficiency of water is felt during the Hathia constellation (early October) and the canal waters are useful only in such contingencies. But if the Hathia rains are not there, the flow in the river is also greatly reduced and it becomes difficult to push the available waters into the canals. Further, the farmers in the upper reaches of the canal, intercept this water for irrigation and release it only after their own demands are met. The Irrigation Department or the administration can do a precious little in such cases. Otherwise also, there has been tremendous sedimentation in the canal beds and their capacity greatly reduced. The water in the Kings Canal somehow manages to reach up to Balat village beyond which it dries up. Similar is the case with the Sugharaul and Pakri distributaries below Umgaon. The irrigation in these villages is dependent on the farmers upstream who block the canal water for their use. The downstream farmers get water, sometimes by requesting upstream farmers and, at times, by removing the blockades in the nights. There are always the chances of violent conflicts in such cases.

As if that were not enough, Nepal constructed a barrage on the River Kamla at Godar on their side of the border, near Bandigram, some 20 years ago and that has resulted further in the dwindling supplies at Jainagar. Bhogendra Jha (1985), former MP has written about the problems faced in this area. He said that, “... in our hunch for the flood control and some irrigation, we constructed embankments on either side of the river and put a weir across the Kamla at Jay Nagar. These embankments were to be extended to Mirchaiya, in Nepal, in accordance with the Indo-Nepal agreement. But we did not do that. That resulted in enhanced floods in many villages in Nepal and they faced submergence. The water flowing southward spreads outside the embankments and causes breaches in the Kamla Canals. Fed up with the delays in the construction of the embankments up to Mirchaiya and our silence over the construction of the ChisaPani Multi-purpose Dam on the Kamla, Nepal has constructed a barrage at Godar near Bandigram, north of the Mahendra National Highway some 30 kilometers north of our Jay Nagar barrage. They have taken out canals from both the ends of this barrage. The flow in both these canals put together is of the order of 1000 cusecs (nearly 30 cumecs) and they are unable to irrigate the main portions in the command but that is sufficient to totally paralyze the Kamla Canal System in India. Just as the Jay Nagar barrage is constructed on the plain lands, the Godar barrage is also constructed on the plain lands and cannot tolerate the onslaughts of floods. Thus, there is no reduction in floods on either side of the border.”

As if that were not enough, Nepal constructed a barrage on the River Kamla at Godar on their side of the border, near Bandigram, some 20 years ago and that has resulted further in the dwindling supplies at Jainagar. Bhogendra Jha (1985), former MP has written about the problems faced in this area. He said that, “... in our hunch for the flood control and some irrigation, we constructed embankments on either side of the river and put a weir across the Kamla at Jay Nagar. These embankments were to be extended to Mirchaiya, in Nepal, in accordance with the Indo-Nepal agreement. But we did not do that. That resulted in enhanced floods in many villages in Nepal and they faced submergence. The water flowing southward spreads outside the embankments and causes breaches in the Kamla Canals. Fed up with the delays in the construction of the embankments up to Mirchaiya and our silence over the construction of the ChisaPani Multi-purpose Dam on the Kamla, Nepal has constructed a barrage at Godar near Bandigram, north of the Mahendra National Highway some 30 kilometers north of our Jay Nagar barrage. They have taken out canals from both the ends of this barrage. The flow in both these canals put together is of the order of 1000 cusecs (nearly 30 cumecs) and they are unable to irrigate the main portions in the command but that is sufficient to totally paralyze the Kamla Canal System in India. Just as the Jay Nagar barrage is constructed on the plain lands, the Godar barrage is also constructed on the plain lands and cannot tolerate the onslaughts of floods. Thus, there is no reduction in floods on either side of the border.”A proposal to modernize these canals is pending for a long time with the Government but no action is being taken over it and the canals are loosing their utility day by day. There has been some stray digging of the canal in certain reaches in the past 2-3 years. The Eastern Kamla Canal was designed for irrigating 3,691 hectares in Kharif and 1053 hectares in the Rabi season. The Western Kamla Canal, including Kings Canal, was supposed to irrigate 24,253 hectares in Kharif and 6,930 hectares in the Rabi season. Thus, the total irrigation from these canals was 27,944 hectares in Kharif and 7983 hectares in the Rabi season.

Table-1 Actual Irrigation From The Kamla Canals (Hectares) | ||||

Year | Kharif | Rabi | Total | % age of Target |

1964-65 | 2,044 | - | 2,044 | 5.69 |

1965-66 | 2,819 | - | 2,819 | 7.85 |

1966-67 | 16,558 | - | 16,558 | 40.09 |

1967-68 | 14,136 | - | 14,136 | 39.35 |

1968-69 | 24,453 | 129 | 24,582 | 68.42 |

1969-70 | 30,381 | 276 | 30,657 | 85.33 |

1970-71 | 26,665 | 751 | 27,416 | 76.31 |

1971-72 | 11,012 | - | 11,012 | 30.65 |

1972-73 | 29,272 | 194 | 29,466 | 82.02 |

1973-74 | 29,107 | 329 | 29,436 | 81.93 |

1974-75 | 11,238 | 507 | 11,745 | 32.69 |

1975-76 | 25,575 | 1,515 | 27,240 | 75.82 |

1976-77 | 23,102 | 1,651 | 24,753 | 68.90 |

1977-78 | 19,187 | 137 | 19,324 | 53.79 |

1978-79 | 20,871 | 1,543 | 22,414 | 62.39 |

1979-80 | 20,454 | 1,335 | 21,789 | 60.55 |

1980-81 | 18,162 | 1,792 | 20,404 | 56.79 |

1981-82 | 18,506 | 754 | 19,260 | 53.61 |

1982-83 | 16,096 | 818 | 16,914 | 47.08 |

1983-84 | 20,267 | 816 | 21,083 | 58.68 |

1984-85 | 10,543 | 1,041 | 11,584 | 32.24 |

1985-86 | 20,069 | 972 | 21,041 | 58.57 |

1986-87 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

1987-88 | 600 | 710 | 1,310 | 3.67 |

1988-89 | 25,000 | 400 | 25,400 | 70.70 |

1989-90 | 20,000 | 1,000 | 21,000 | 58.45 |

1990-91 | 20,000 | 570 | 20,570 | 57.25 |

1991-92 | 8,600 | 1,100 | 9,700 | 27.00 |

1992-93 | 7,170 | 1,100 | 8,270 | 23.02 |

1993-94 | 11,350 | 1,660 | 13,010 | 36.21 |

1994-95 | 9,990 | 540 | 10,530 | 29.31 |

1995-96 | 11,032 | 1,115 | 12,147 | 33.77 |

1996-97 | 13,254 | 370 | 13,624 | 37.87 |

1997-98 | 10,485 | 369 | 10,854 | 30.17 |

1998-99 | 11,023 | 381 | 11,404 | 31.78 |

1999-2K | 12,005 | 568 | 12,573 | 34.95 |

2000-01 | 10,466 | 781 | 11,247 | 31.31 |

2001-02 | 11,020 | 133 | 11,153 | 31.04 |

2002-03 | 13,622 | 130 | 13,752 | 38.28 |

2003-04 | 22,045 | 545 | 22,590 | 62.88 |

2004-05 | 20,050 | 731 | 20,781 | 57.84 |

2005-06 | 20,100 | 350 | 20,450 | 56.92 |

Source : Water Resources Department, Government of Bihar, (At, Jainagar and Patna) | ||||

A cursory look at the table suggests that there is no consistency in the irrigation figures from the canals. It may be rated satisfactory in some years but, in some years, their performance becomes questionable. There has been some improvement in irrigation figures in past two years and that may be attributed to some re-sectioning of the canal in certain reaches. The irrigation figures from the Kamla Canals do not evoke confidence among the farmers of the region and no farmer bases his agriculture depending on the Kamla Canals.

Comptroller General of Accounts (Civil), in his report of 1977-78 has commented on the performance of the Kamla Irrigation Scheme. It says, ....The Kamla waters carry a lot of sediments in the flow during the floods which results in the blocking of the channels leading to the canal head-works. As the demand increases, the supply is impeded. To meet this problem, a weir was constructed at an estimated cost of Rs. 64.09 lakhs in March 1964. In the month of July 1964, another scheme was launched by the Government in the name of the Kamla Irrigation Scheme at an estimated cost of Rs. 57.53 lakhs, (Rs. 46.98 lakhs for the western and Rs. 10.55 lakhs for the eastern canal system) so as to make use of the diverted water from the weir. These estimates were revised to Rs. 147.79 lakhs in July 1970 and Rs. 335.22 lakhs in September 1976. There was no provision for making the village channels in this budget and the farmers could not build them because the availability of water was uncertain. They also did not have the expertise to construct these channels. However, the canals were completed in 1968-69 but the village channels were not. Till 1978, only the budget estimates were being prepared for the village channels.

Not only the availability of water was uncertain in Kamla Canals, they have created other problems also in the region. The western canal travels in the easterly direction, from Jainagar to Umgaon, but the land slopes from north to south and the canal acts as an earthen dam for the rainwater coming from north. This water stagnates on the northern face of the canal. This damages the crops north of the canal in the villages like Lahernia, Mahadeo Patti and Kasera where it remains for up to a fortnight. The canal virtually has no use for these villages. The matter does not end with the main canal alone. The distributaries have their own share in worsening the situation. One such incident took place in the Bituhar village of Harlakhi block of the Madhubani district where severe water logging took place because of the Jiraul distributary. The farmers of these villages did not take things for granted and took the matter up to the Requisition Committee of the Bihar Vidhan Sabha.

It so happened that this distributary of the Kamla Canal was to pass through the eastern side of the Bituhar village. But, in that case, it would pass through the land of the mahant of the Pachahari Math. The executive engineer of the Kamla Canal was under the influence of the spiritual head of the Math and he got the alignment of the canal changed to the western side of the village. The farmers protested and gave many petitions to restore the alignment of the distributary but these requests had to be made to the same executive engineer who was already influenced to disregard them. The distributary was constructed and water logging followed. A farmer from the village, Devendra Singh, along with 51 other farmers lodged a protest with the Vidhan Sabha for the redressal of their problem. Vidhan Sabha constituted a committee to look into the matter and the report of the committee was published in 1981.

The committee report says, ... The crops of the poor farmers are destroyed year by year due to water logging. The houses of the poor Harijans, too, collapsed in large numbers each year.... The Irrigation Department should compensate for the losses incurred by the people. The Committee contacted the Relief Commissioner if he could help the farmers in the matter who opined that if the losses were incurred because of the mistakes of the Irrigation Department, the compensation must also come from them. The Relief Department comes forward to help people only in case of natural calamities. The rent for the land can be waved off in case of the waterlogged land only till such time that there is water on the land. Even this can be done only at the recommendation of the Collector of the district, he maintained.

The Committee wrote further that, … Those, whose land is acquired for the purpose of constructing the canal do not get water, their land gets waterlogged for technical reasons, their houses collapse and the Government watches all these events helplessly. What sort of justice is this? The department must look at the problem from a humanitarian angle. It is a well-known fact that the guilty should be punished and not the innocent The sole reason for water logging is the construction of the canal.

The fact is that a large chunk of land is waterlogged in the Kamla Project because of the embankments and the canals. The Government has submerged the land but, not to talk of any compensation, the process of providing land remissions is so complicated that it is impossible to get any relief on that count. Despite the recommendation of the Committee of the Vidhan Sabha in this case, no action was taken. Bituhar is just an exam-ple but there are so many villages, from Jainagar to Arerh in the Kamla Basin that suffer from waterlogging, sand casting, breaches in the canals and non-availability of water with nobody to look after the peoples interests.

7. Revenue Collection in the Kamla Canals

The process of collection of the irrigation tax is equally cumbersome, humiliating and intimidating for the farmers. This is no different than other large canals like the Kosi or the Gandak. Whether water is released into the canals or not or whether irrigation has been provided at all; the bills come in time. No solution to this problem has been found out so far. Baidya Nath Yadav MLA (1966) had raised this point in the Bihar Vidhan Sabha, way back in 1966, saying, “...the tax is extorted illegally from 90 percent farmers on the plea that they should deposit it now and it will be returned later. When the farmers claim the reimbursement; their requests are not heard ...The Karmacharis of the department also demand money illegally...Those who do not own land in the village, also get the notice for making payment. If the crop is destroyed following a breach in the canal, still, the notices are served. The Karmacharis of the department draw a map of the irrigated area sitting at home without verifying whether the land that they have marked as irrigated is a house or a threshing ground. The payments are sought from all.”

Such charges are being leveled against the revenue staff right from the beginning of irrigation in the area. Irrigation from the Kamla Canal started on a very modest scale in 1964-65 but when it came to the billing for the irrigation charges, the farmers of as distant places as BeniPatti got the notices while the water was not released into those canals. They were ill treated by the staff of the department and their bullocks were confiscated by the revenue staff, besides threatening them of dire consequences. Nothing has changed in the Kamla Project since then.

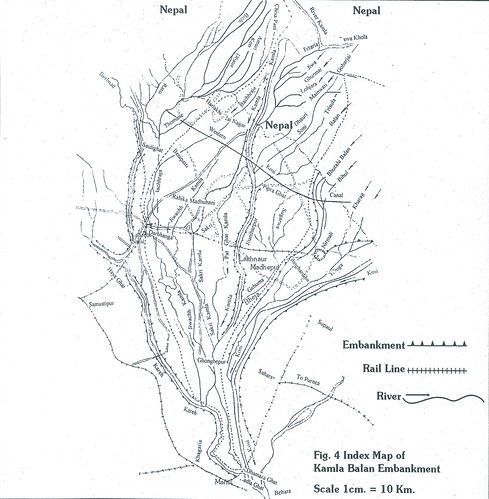

8. The Kanila Flood Protection Scheme

Flood, it appears, was not a big issue in the Kamla basin in the eighteenth and the nineteenth century. There were some zamindari embankments, at places, and the people had their own arrangements of coping with the floods. The British Government used to tread very cautiously in taking up any scheme in the basin because it had no control over what Nepal would do in her territory. Till 1942, the British were opposed to the embankments and wanted their systematic demolition and they had learnt this lesson the hard way when the embankments (earthen walls of trapezoidal cross-section constructed between the river and the human settlements) constructed on the Damodar in the middle of nineteenth century failed to control floods and created many other problems instead. That forced the British to improve the drainage and achieve a greater degree of moderation of floods and they preferred leaving the river to their own devices. Before they left India, however, the British had initiated large dam projects like the ones on the Damodar and Barahkshetra Dam on the Kosi too had started making news. However, all that was done for tackling floods in independent India was building embankments.

Without going into the details of the impact of embankments over the river and the debate that ensued in the past over the choice of embankments as a device to control floods, suffice here to say that the floodwater of a free flowing river carries a lot of sediment load (silt, sand and stones), which is spread over a large area along with the floodwaters. This is how the rivers build their delta. The embankments not only prevent the floodwaters from spilling: they also trap the suspended sediment load within them. Thus the process of natural land building of the river is thwarted, the sediments get deposited within the embankments thereby successively raising the bed of the river and, in turn, the flood level within the embankments. The embankments have to be raised keeping in pace with the rising bed level of the river. There is a practical limit to which the embankments can be raised and maintained. With every rise of the embankment, the surrounding countryside turns into low-lying lands, in the same proportion.

Rising bed and flood levels within the embankments threaten the embankments of failure due to overflowing seepage or slumping down of the slopes of the embankments, to the detriment of the people residing in the surrounding countryside. The embankments may also breach because of the flow under pressure through the holes of rats muskrats and foxes, which these creatures dig through the body of the embankments.

The discharge from a tributary river cannot enter the main river because of the construction of the embankments. This water, from the tributary will either back-flow into the countryside or start flowing parallel to the embankments on the main river flooding new areas, hit her to unknown to experience flooding. The obvious solution to this problem is to construct a sluice gate at the confluence of the two rivers. However, it is difficult to operate such sluice gates during the monsoon months for the fear that if the water level in the main river is high, there is a possibility of the water from the main river flowing back into the tributary. Sluice gates often get jammed after a few years of their construction due to deposition of sand in their front, on the riverside. Thus sluice gates or no sluice gates, the tributary water will spread into the countryside. These sluice gates can be operated only after the rains are over and the water level within the embankments has considerably gone down. By the time the damage is already done, as the tributary cannot discharge its water into the main channel.

When the sluice gates fail to perform, it is often proposed to construct the embankments over the tributary, to prevent its spill. Now, the rainwater that falls within the two embankments of the main river and that of the tributary, has nowhere to escape. It becomes a case of water locking. This water can only evaporate into the atmosphere or seep through the ground. The other option is to pump it back into any of the two rivers. If pumping out the floodwater were the solution, this could have been resorted to even without constructing the embankments, the sluice gates or the secondary embankments. Should a breach occur in any of the embankments mentioned above: the people residing within the two embankments will not find time to react to surges of water gushing out of the gaps and which will confine them to their watery graves.

The embankments prevent the rainwater that would have entered freely into the river and this water accumulates outside the embankments causing severe water logged conditions in the countryside. Waterlogging is further compounded by seepage through the main body of the embankments. Besides, the river water contains a lot of fertilizing silt in its flow, which used to spread over the land along with the floodwater prior to the construction of the embankments. This silt gets trapped between the embankments and the countryside slowly looses its fertility which has got to be replenished artificially by adding fertilizers and which has to be paid for.

Sometimes, for topographical or political reason, embankments are built only on one side of the river. Everything remains the same in this case too, except that the floodwater is now free to flow on the side opposite of the embankment. Seeking flood protection through embankments is walking into a trap where every action leads to a new and costly measure and the problem goes on deteriorating with time.

A section of engineers, however, believe that when a river is embanked, the waterway available in the river narrows and which results in the increased velocity in the rivers flow. With the rise in the velocity of rivers water, the eroding capacity of the river increases. When the flood-water erodes the banks and the bottom of the river, its width and depth would increase and so will be its discharge carrying capacity. Thus, the river is re-sectioned and it will carry more discharge, causing the floods to decline.

The debate whether the embankments add to or reduce the flood problem is still inconclusive in the technical circles. We have such a strong case against the embankments, if we do not want to build them. At the same time, the argument in favour of the embankments is equally sound and scientific. Thus, the arguments, for and against the embankments, both, are highly technical and equally compulsive that no body can find any fault with either of them. The decision, whether to build embankments or not, however, is mostly taken by politicians and, for obvious reasons, the engineers are made to defend them. The engineers, irrespective of their stature, are so amenable to the politicians influence that the politicians use them at their will and get the things done the way they like. These inferences are not without foundation.

Thus, whatever happened in the field of flood control was after 1954 and a scheme to embank the Kamla was proposed after the embankments on the Kosi were sanctioned. According to the original scheme, embanking of the Kamla was proposed, in 1956, from Chisapani, in Nepal, to Darjia in Madhubani, over a distance of 149.6 kilometers. The distance of Darjia from the Nepal border is 101.6 kilometers. The scheme was estimated to cost Rs. 4.04 Crores and was expected to protect 1.92 lakh hectares of land from the floods of the Kamla.

The construction of these embankments, from Jainagar to Jhanjharpur was started in 1956 and completed in 1960. They were extended up to Darjia in 1962. In the third phase, the embankments were further extended up to Kothram in 1982-84.

What followed the embankments on the Kosi is recorded elsewhere and we will not go into those details here. We will take a stock of the situation in the Kamla basin in this section. There is a striking resemblance between the Kosi and the Kamla embankments to that of a blacksmith and the goldsmith. The impact of the sledgehammer of the blacksmith is heard and felt even at far distant places but the goldsmith has a miniature hammer and one has to concentrate to hear this sound. The Kosi’s hammer strikes at long intervals and all concerned people feel the impact of it but in the case of Kamla, the strokes are relatively mild but many. The Kamla embankment breaches wholesale and without any gap ever since it was constructed. The river tries to break its shackles frequently in search of freedom. It is a small river as compared to the Kosi and those living on the banks of this- embanked river, often cut the embankments to drain the water stagnating outside the embankments. This is also done with a hope that the river water will spread all over the land and revive its fertility. Because of the construction of the embankments on either side of the riverbanks, the riverbed has gone up considerably and the adjoining areas, as a result, have gone below the level of the river in the same proportion. With the breach in the embankment, whether deliberate or otherwise, the lower lying land gets filled up with sediments emerging out from the gap and water logging, at least, at the local level comes to an end. Breaching of the embankments by the local people is possible only on smaller rivers as the effects of tampering with a river like the Kosi or the Gandak may prove to be too devastating and worse unpredictable.

However, it should not be construed, in any way, that the floods in the Kamla basins are less devastating than that of the Kosi. If two trains, say, a Rajdhani Express and a passenger train meet with an accident simultaneously, then the Rajdhani Express gets more publicity and importance than that of the passenger train. Similar is the difference between the failure of the embankments of these two rivers.

However, it should not be construed, in any way, that the floods in the Kamla basins are less devastating than that of the Kosi. If two trains, say, a Rajdhani Express and a passenger train meet with an accident simultaneously, then the Rajdhani Express gets more publicity and importance than that of the passenger train. Similar is the difference between the failure of the embankments of these two rivers.The first phase of the Kamla embankments was the construction of the embankments from Jainagar to the Jhanjharpur railway bridge and this was completed in 1960. Before these embankments could be completed, the second phase of the project was announced that the embankments would be extended further up to Darjia, 21 kilometers further south of the rail bridge. The local leaders and the population were convinced that the river water used to converge at the rail bridge of Jhanjharpur and then emerge out of the bridge like an arrow hitting directly a population of about 150,000 of the blocks of Jhanjharpur, Madhepur, Ghanshyampur. Biraul, and Kusheshwar Asthan. This water was not only destroying the crops of the area, it was also destroying houses in large numbers and some steps should be taken to ease the situation. The state Government also held similar views but it had to wait for the recommendations of a High Level Committee report. This committee comprised of the Chief Engineers of the Kosi Project, the Irrigation Department of Bihar, the Central PWD and the North East Railway besides many others. Central Water and Power Commission also wanted that integrated and comprehensive plans should be made for the lower areas, which should also incorporate the possible impact of the Kosi and the Bagmati and if it meant delays, then they were unavoidable.

The problem with the Kamla-Balan embankments was that the original stream was that of the Balan, which the Kamla joined later, in 1954. It was beyond the capacity of the Balan to accommodate the additional flow of the Kamla in its waterway. Also, the bridge on the Sakri-Jhanjharpur rail line, close to Jhanjharpur, was designed keeping in view of the flow in the Balan and was only 37 meters long. Even this bridge was incapable of accommodating the flow of the combined stream. After completion of the Jainagar-Jhanjharpur embankment on the Kamla-Balan, it was realized that the waterway was grossly undersized and a mistake had been committed. The floodwaters used to emerge from this bridge like a bullet and hit the villages located south of it. Later, without increasing the waterway through this bridge, the Kamla-Balan embankment was extended up to Darjia. The Government of Bihar, at its own expenses, widened this bridge to 107 meters but this widening was only temporary as the Railways had proposed a width of 146 meters for the bridge. It had also raised the Lohna Road-Jhanjharpur Rail line by 1.5 meters. This rail line used to cross the Kamla close to Jhanjharpur railway stations. Thus, the plans were afoot to raise and widen this bridge but this permanent bridge could not be built till 1965 while the embankment till Darjia was complete in 1962.

This state was not suited for the safety and security of embankment and the rail bridge. The newly constructed embankment of the Kamla-Balan got breached near Ramghat in 1963, south of the Jhanjharpur bridge, in the very first year of its commissioning and inundations had to be faced in the villages of Kharwar, Gangapur, Gunakarpur, and Belhi etc. In 1964, the embankments of the river breached at four places including the one near Daiya Kharbar (it had breached here last year also) and many villages of Jhanjharpur, Madhepur, and Manigachhi blocks faced severe flooding. The people here were not used to facing man made floods like this and it was a new experience for them. The river eroded a portion of Lakshmipur village near Jainagar in this years floods.

9. The First Major Setback To The Kamla Embankments 1965

But the kind of devastation that was faced in the floods of 1965 was unprecedented. There was very heavy rain in the catchment areas of the Kamla in Nepal in the first week of July. A partly constructed bridge on the Kamla-Balan, near Jhajharpur, was standing in the way of this water that approached Jhanjharpur. The water level rose by 2 meters within 10 hours of the rains on the 8th July and it far exceeded the maximum flood level of the river in 1964 and smashed the approach road of the railway line and caused 21 breaches on either side of the embankments. The collector of Darbhanga, J.C. Jately, got the information about the disaster and left for Jhanjharpur but had to terminate his journey at Pipra.

The floods took away the railway line and the entire transport system of the area. The grains kept for relief operations were spoiled in the godowns and whatever food material was distributed was not fit for the consumption for even the cattle. Seedlings and the freshly transplanted paddy over a vast area were destroyed and a large number of houses had collapsed. ... 7th and 8th July were the last auspicious days for marriages in the season in Mithila but many newly married couples were left stranded at the railway stations and could not reach their destinations. An unprecedented situation was created there and the communication was snapped. It was quite likely that many marriages might not have been consummated.

Then the usual mud slinging, so common to such occasions, started. The Commissioner of Darbhanga J. S. Bali, issued a statement in which he had said that although the floods were there, the reports about the damages had been exaggerated. There was a strong public reaction against his statement. Wrote a correspondent in the Indian Nation-Patna, “... if Mr. Bali had been an ordinary official, such an attempt to run down eye-witness accounts published in the press would not have mattered. No one unaffected by the floods would have cried over his beer about it. But he happens to be the divisional commissioner, the virtual Governor of his division on whose appreciation of the situation would depend the nature, extent and expedition of relief. At any rate if he has been reported correctly, his statement is likely to cause despair among the flood victims who are passing their day and night in the open on embankments, roads and all available uplands with little food and suffering untold hardship.”

It was an established fact that the floods were caused by the rail bridge at Jhanjharpur. After the incident, the Irrigation Department of the state and the Ministry of Railways, under the Central Government, traded charges on each other for the disaster. The then Irrigation Minister of Bihar, Mahesh Prasad Sinha, leveled charges against the railways that had they completed the bridge on time, the accident could have been averted and that the railway authorities paid no heed to the repeated advice and warnings of the engineers of the Irrigation Department. He reiterated his stand in the Bihar Vidhan Sabha on the 20th July 1965 and Sahdeo Mahto, on behalf of the Government, replied to a call attention motion explaining the existing situation, on the 6th August 1965. Similar charges were leveled by Hari Nath Mishra and Prem Chandra Mishra, MLAs, against the railways. This blame game entered a very interesting phase as the Railway Minister at the center, Dr. Ram Subhag Singh, was also an MP from Bihar. He flatly denied the charges leveled by Mahesh Prasad Sinha and Hari Nath Mishra that the railways had ever made a bridge that had obstructed the flow of water. He maintained that the North Eastern Railway had made only the approach road for the three bridges of 16 feet x 40 feet (5 meters x 12.2 meters) and in lieu of it, the railways had closed the mouth of one 20 feet x 10feet (6 meters x 3 meters) bridge. Therefore the charges leveled by the State Government on the Railway Department were baseless. He said that the basic reason for this years devastating flood was the heavy rains in the Nepal portion of the catchment of the Kamla and the construction of the embankments on the either side of the river by the state Government.” He added that the bridges of the Railways were made keeping in view the discharge of the River Balan and not for the combined flow of the Kamla Balan. Thus, both the sides had arguments in its armor to counter the allegations of the other.

The Chief Engineer of the CWPC, P. N.Kumra visited the bridge site on the 20-21st July and instructed the Railway Engineers that the height of the rail approach bund should be reduced by 1.5 meters and the other structures should be completed immediately. Dr. K.L.Rao, Central Irrigation Minister also visited Jhanjharpur on the 2nd August and asked the Railways to provide 20 vents in the bridge instead of 16 and the suggestion was accepted by the Railway Authorities. The engineers exercised greater restraint than their political counterparts in dealing with each other.

The government of Bihar threw all its experienced engineers and all its might in the repairs of embankments although it, took some time to organize things as it requires dry earth to be placed on the embankments to plug the breaches and this was not available throughout the rainy season. The Government was charged of inefficiency and the charges of corruption remains a permanent undercurrent in such situations.