Abstract

Background: The problem of high fluoride concentration in groundwater resources has become one of the most important toxicological and geo-environmental issues in India. Excessive fluoride in drinking water causes dental and skeletal fluorosis, which is encountered in endemic proportions in several parts of the world. World Health Organization (WHO) guideline value and the permissible limit of fluoride as per Bureau of Indian Standard (BIS) is 1.5 mg/L. About 20 states of India, including 43 blocks of seven districts of West Bengal, were identified as endemic for fluorosis and about 66 million people in these regions are at risk of fluoride contamination. Studies showed that withdrawal of sources identified for fluoride often leads reduction of fluoride in the body fluids (re-testing urine and serum after a week or 10 days) and results in the disappearance of non-skeletal fluorosis within a short duration of 10–15 days.

Objective: To determine the prevalence of signs and symptoms of suspected dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis, along with food habits, addictions, and use of fluoride containing toothpaste among participants taking water with fluoride concentration above the permissible limit, and to assess the changes in clinical manifestations of the above participants after they started consuming safe drinking water.

Materials and Methods: A longitudinal intervention study was conducted in three villages in Rampurhat Block I of Birbhum district of West Bengal to assess the occurrence of various dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal manifestations of fluorosis, along with food habits, addictions, and use of fluoride containing toothpaste among the study population and the impact of taking safe water from the supplied domestic and community filters on these clinical manifestations. The impact was studied by follow-up examination of the participants for 5 months to determine the changes in clinical manifestations of the above participants after they started consuming safe drinking water from supplied domestic filters and community filter with fluoride concentration below the permissible limit. The data obtained were compared with the collected data from the baseline survey.

Results: The prevalence of signs of dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis was 66.7%, 4.8–23.8%, and 9.5–38.1%, respectively, among the study population. Withdrawal of source(s) identified for fluoride by providing domestic and community filters supplying safe water led to 9.6% decrease in manifestation of dental fluorosis, 2.4–14.3% decrease in various manifestations of skeletal fluorosis, and 7.1–21.5% decrease in various non-skeletal manifestations within 5 months. Following repeated motivation of participants during visit, there was also 9.7–38.1% decrease in the usage of fluoride containing toothpaste, and 9.8–45.3% and 7.3–11.9% decrease in the consumption of black lemon tea and tobacco, respectively, which are known sources of fluoride ingestion in our body and have an effect on the occurrence of various manifestations of fluorosis following drinking of safe water from domestic and community filters. Conclusion: Increased prevalence of dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis was found among the study population. Withdrawal of source(s) identified for fluoride by supplying domestic and community filters, dietary restriction, and other nutritional interventions led to decrease in manifestation of the three types of fluorosis within 5 months.

Key words: Diet, Fluorosis, Health impact, Intervention, Safe water key words:

Introduction

Fluoride is one of the important factors in water quality management due to its adverse health effects. The problem of high fluoride concentration in groundwater resources has become one of the most important toxicological and geo-environmental issues in India. Excessive fluoride in drinking water causes dental and skeletal fluorosis, which is encountered in endemic proportions in several parts of the world.1 World Health Organization (WHO) guideline value and the permissible limit of fluoride as per Bureau of Indian Standard (BIS) is 1.5 mg/L.2 About 20 out of 35 states and union territories of India were identified as endemic for fluorosis3 in these regions are at risk of fluoride contamination. Fluorosis is known to occur due to the entry of excess fluoride into the body. It is a slow, progressive, crippling malady that affects every organ, tissue, and cells in the body, and results in health complaints that overlap with several other disorders. Most of the fluorides are readily soluble in water. Prolonged ingestion of fluoride above permissible level through water is the major cause of fluorosis.

Fluorosis disease can occur in three forms: dental fluorosis, skeletal fluorosis and non-skeletal fluorosis. Dental fluorosis occurs in the permanent teeth in children after 8 years of age.3,4 Skeletal fluorosis affects the bones and major joints of the body.5,6 Non-skeletal fluorosis affects invariably all the soft tissues, organs, and systems of the body.7 Dental fluorosis is a good indicator of exposure to excessive amounts of fluoride. The main natural source of inorganic fluorides in soil is the parent rock. Fluoride can also enter the through food and fluoridated dental products as well as drugs. To confirm diagnosis of fluorosis, the fluoride is mainly estimated in serum, drinking water, and urine.7 10–40% districts are affected in Assam, Jammu & Kashmir, Kerala, Chattisgarh and West Bengal.8 In West Bengal, fluoride was first detected at Bhubanandapur in Nalhati I block of Birbhum district in 1996. During a rapid assessment survey by Public Health Engineering Department, Government of West Bengal (2005), 729 sources were found to be contaminated with fluoride above 1.5 ppm in 43 blocks of seven districts of West Bengal, with the affected population being approximately 2.26 lakhs. Fluoride level in West Bengal varies from 1.1 to 4.47 Studies show that withdrawal of sources identifi ed mg/L.9for fluoride often leads to reduction of fluoride in the body fluids (re-testing urine and serum after a week or 10 days) and results in the disappearance of non-skeletal fluorosis within a short duration of 10–15 days.9

Fluorosis is an impending public health problem in West Bengal affecting a large number of population, and Birbhum is one of the affected districts with seven affected blocks. It is evident from previous studies that withdrawal of source(s) identified for fluoride leads to reduction of fluoride in body fluids and shall result in disappearance of health problems emanating from non-skeletal fluorosis within a short period.7 As intervention studies are scarce to prove the above hypothesis, the present intervention study was conducted to see the impact of drinking safe water which is the main known intervention for prevention and treatment of the toxicity caused by clinical course of fluorosis.

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of signs and symptoms of suspected dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis, along with food habits, addictions, and use of fluoride containing toothpaste among participants taking water with fluoride concentration above permissible limit.

To determine the changes in clinical manifestations of the above participants after consumption of safe drinking water.

Materials and Methods

A longitudinal intervention study was started in the month of December 2008 in Junitpur, Kamdebpur, and Noapara villages in Rampurhat Block I of Birbhum district of West Bengal and completed in the month of September 2009 to assess the occurrence of various dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal manifestations of fluorosis and the impact of taking safe water on these manifestations.

Seven blocks of Birbhum district of West Bengal were endemic for fluorosis. Out of these seven blocks, Rampurhat Block I was selected randomly for the study. Within this block, all the three affected villages, i.e. Junitpur, Noapara, and Kamdevpur, with the fluoride content in their tube wells varying from 2.6 to 11 mg/L (PHED report 2008) and with a permissible limit of

In Noapara village, as there was no safe source, a community filter was installed. Eighteen families belonging to Noapara village, having 41 family members, including some tribal families taking water from the community filter were included in the study.

All the selected families had a past history of taking water from an unsafe source (a tube well having fluoride concentration higher than the permissible level) situated nearby before using the water from the domestic and community filters.

The supplied filters remove fluoride by adsorption method with activated alumina used as adsorbent, which is a standardized method of removing fluoride from water and accreted by PHED, Government of West Bengal.

Ethical clearance was obtained prior to the initiation of the study. After taking informed consent and explaining the purpose of the visit, the members of the families selected were interviewed with a pre-designed and pre-tested oral questionnaire and clinically examined for identification of signs and symptoms of suspected dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis, along with their food habits, addictions, and use of fluoride containing toothpaste, and a checklist was used to obtain the baseline data in the fi rst visit (December 2008) for assessing the prevalence of various clinical manifestations of suspected fluorosis among them before they started using safe water from the supplied filters for drinking and cooking purposes.

The family members were motivated to use only filter water for their drinking and cooking purposes, and the use of filters by the family members continuously by the field workers.

The family members were subsequently reexamined at alternate months, i.e. February, April, June, August, and September, in the year 2009 to determine the changes in clinical manifestations after consumption of safe drinking water from the supplied domestic filters and community filter. The data obtained were compared with the collected data from the previous visit and baseline survey at the time of analysis. The analysis was done separately for those drinking water from domestic filter and those drinking from community filter, with an objective to find out any difference of health impact between the two.

During each follow-up visit, enquiries were made regarding the presence or absence of any difficulties in using the filters, their satisfaction level, and the user-friendliness of the filters.

Water was also collected from the filters for chemical (including fluoride level) and bacteriological testing, and their efficacy in removing fluoride and bacteria was monitored regularly. The families having some difficulties in using the filters were explained the ways to overcome such difficulties after proper inspection and minor repair of their filters by the accompanying chemist and technician.

Dental fluorosis, skeletal fluorosis, and non-skeletal fluorosis were assessed by case definitions and diagnostic criteria developed by Fluorosis Research and Rural Development Foundation, New Delhi.3,5,7 Data collected were analyzed by suitable statistical methods.

Results

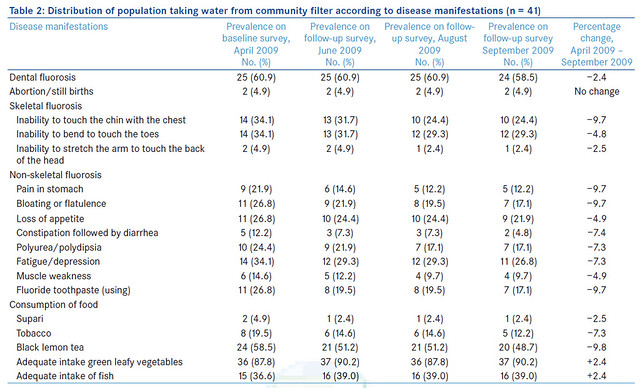

57.1% and 58.5% of the participants using domestic and community filters, respectively, were found to be still suffering from dental fluorosis, with 9.6% decrease from the baseline level (66.7%) in participants drinking water from domestic filters and 2.4% decrease from the baseline level (60.9%) in participants drinking water from community filters [Tables 1 and 2]. 16.6% and 17.1% of the participants using domestic and community filters, respectively, were still using fluoride containing toothpaste, with a signifi cant 35.8% and 9.7% decrease from the baseline level (52.4% and 26.8%, respectively). 19.0% and 48.7% of the participants using domestic and community filters, respectively, drank black lemon tea containing high fluoride, which showed a signifi cant 45.3% and 9.8% decrease from the baseline level (64.3% and 58.5%, respectively) [Tables 1 and 2]. 88.1% and 90.2% of the participants using domestic and community filters, respectively, took plenty of green leafy vegetables containing antioxidants, with a signifi cant 38.1% and 2.4% increase from the baseline level (50% and 87.8%, respectively). 61.9% and 39% of the population using domestic and community filters, respectively, took adequate amount of fish, followed by less frequent amount of egg and meat, with 14.3% and 2.4% increase from the baseline level (47.6% and 36.6%, respectively) [Tables 1 and 2]. Polyurea /polydipsia (38.1%), fatigue or depression (30.9%), and bloating or flatulence (28.6%), followed by loss of appetite (23.8%) and pain in stomach (21.4%) were the symptoms of non-skeletal fluorosis among those participants supplied with domestic filters.

Following intake of safe water from domestic filters, polyurea and polydipsia decreased to 21.5%, loss of appetite to 16.7%, followed by bloating or flatulence which showed a 12% decrease, constipation followed by diarrhea, and pain in stomach, each showing 11.9% decrease, and decrease in muscle weakness was 7.1% [Table 1]. Fatigue or depression (34.1%), loss of appetite and bloating or flatulence (26.8%), followed by polyurea/ polydipsia (24.4%), pain in stomach (21.9%), muscle weakness (14.6%), and constipation followed by diarrhea (12.2%) were the symptoms of non-skeletal fluorosis among those participants supplied with community filters. A decrease was found in all the symptoms as follows: pain in stomach and bloating or flatulence (9.7%), constipation followed by diarrhea (7.4%), polyurea and polydipsia, and fatigue or depression (7.3% each) and muscle weakness and loss of appetite (4.9% each) [Table 2].

The most common signs of skeletal fluorosis in participants supplied with domestic filter were inability to touch the chin with chest (23.8%), followed by inability to bend to touch the toes (11.9%), and inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head (4.8%), which decreased to 14.3%, 7.14% and 2.4%, respectively, in the follow-up survey conducted after they started drinking water from domestic filter [Table 1]. In participants supplied with community filter, both inability to touch the chin with chest and inability to bend to touch the toes (34.1% each) were common symptoms of skeletal fluorosis, followed by inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head (4.9%). In the follow-up survey conducted after they started drinking water from community filter, the levels decreased to 9.7% for inability to touch the chin with chest, 4.8% for inability to bend to touch the toe, and 2.5% for inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head [Table 2].

The most common signs of skeletal fluorosis in participants supplied with domestic filter were inability to touch the chin with chest (23.8%), followed by inability to bend to touch the toes (11.9%), and inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head (4.8%), which decreased to 14.3%, 7.14% and 2.4%, respectively, in the follow-up survey conducted after they started drinking water from domestic filter [Table 1]. In participants supplied with community filter, both inability to touch the chin with chest and inability to bend to touch the toes (34.1% each) were common symptoms of skeletal fluorosis, followed by inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head (4.9%). In the follow-up survey conducted after they started drinking water from community filter, the levels decreased to 9.7% for inability to touch the chin with chest, 4.8% for inability to bend to touch the toe, and 2.5% for inability to stretch the arm to touch the back of the head [Table 2].Discussion

The overall prevalence of dental fluorosis among the study participants was found to be 60.9–66.7% in this study. Choubisa in his study conducted in southern Rajasthan found the overall prevalence of dental fluorosis to be 45.7%.10 Bharati et al., in their study conducted in Gudag and Bagalkot districts of Karnataka, found the prevalence of dental fluorosis to be 35%.11 Yellowish-brown discoloration of teeth with horizontal streaks was the most common symptom of dental fluorosis, followed by blackening/pitting/chipping of teeth. Bharati et al. reported browning of teeth in 64.29% and pitting of teeth in 32.4% subjects.11 Similar positive correlation between fluoride concentration and Dental Fluorosis Index (DFI) score was also found in studies by Ruan et al.,12 Mann et al.,13Acharya,14 and Kumar.15

Prevalence of manifestations of skeletal fluorosis was found to be 23.8–34.1% in this study. Bharati et al., in their study performed in Gudag and Bagalkot districts of Karnataka, found the prevalence of skeletal fluorosis to be 17% and both types to be 12.67%.11 Choubisa in his study conducted in southern Rajasthan found that the overall prevalence of skeletal fluorosis was 22%.10 The most common sign among skeletal fluorosis patients was found to be inability to touch the chin with chest in participants supplied with domestic filter and community filter (23.8% and 34.1%, respectively) and inability to bend to touch the toe in participants supplied with community filter (34.1%). Joint pain was found in 31.87% subjects in the study done by Bharati et al. Narayana et al. reported joint pain and neck stiffness in 50–70% of cases.16 Shashi et al., in their study conducted in three endemic areas of Punjab state, observed back pain (73%) and neck pain (34%) as the symptoms of skeletal fluorosis.17

Prevalence of manifestations of skeletal fluorosis was found to be 23.8–34.1% in this study. Bharati et al., in their study performed in Gudag and Bagalkot districts of Karnataka, found the prevalence of skeletal fluorosis to be 17% and both types to be 12.67%.11 Choubisa in his study conducted in southern Rajasthan found that the overall prevalence of skeletal fluorosis was 22%.10 The most common sign among skeletal fluorosis patients was found to be inability to touch the chin with chest in participants supplied with domestic filter and community filter (23.8% and 34.1%, respectively) and inability to bend to touch the toe in participants supplied with community filter (34.1%). Joint pain was found in 31.87% subjects in the study done by Bharati et al. Narayana et al. reported joint pain and neck stiffness in 50–70% of cases.16 Shashi et al., in their study conducted in three endemic areas of Punjab state, observed back pain (73%) and neck pain (34%) as the symptoms of skeletal fluorosis.17In the present study, tobacco consumption in any form was found in 19.5–14.3% of the subjects. Kubakaddi et al. observed that 40% of the tobacco chewers were suffering from dental and skeletal fluorosis.18 It is evident from previous studies that withdrawal of source(s) identified for fluoride leads to reduction of fluoride in body fluids and shall result in disappearance of health problems emanating from non-skeletal fluorosis within a short period.9 The present study also showed 7.1–21.5% decrease in various non-skeletal manifestations, following drinking of safe water from domestic and community filters. Prevalence of symptoms of skeletal fluorosis was more common among participants taking water from the community filter and the impact of health education and motivation was less among them, leading to a lesser decrease in the percentage of symptoms of skeletal and non-skeletal fluorosis.

Percentage of changes in dental, skeletal, and non- skeletal fluorosis was more marked among domestic filter users in comparison to community filter users. Constant supervision and individual motivation of participants regarding the use of filter water for cooking and drinking, avoidance of fluoride containing toothpaste, and modification of diet and addictive items was found to be more effective among domestic filter users in comparison to community filter users, suggesting that domestic filters are more useful as a public health measure to mitigate the problem of fluorosis at the community level.

Conclusion

It is evident from this study that fluorosis is a definite public health problem in the selected block of Birbhum district, with increased prevalence of dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis found among the study population. Withdrawal of source(s) identified for fluoride by supplying domestic and community filters leads to decreased manifestations of the three types of fluorosis within 5 months following drinking of safe water from domestic and community filters. There was also decrease in the usage of fluoride containing toothpaste, consumption of black lemon tea and tobacco use, which are known to have added infl uence on the occurrence of disease manifestations. There was also an increase in the intake of green leafy vegetables and fish rich in antioxidants and protein after repeated motivation, which is known to prevent the disease to some extent. More extensive studies involving large group of population may be needed in future to measure the impact. Supply of safe water with nutritional interventions based on the above findings may be necessary to combat the problem of fluorosis.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by UNICEF, Kolkata. Support and cooperation rendered by Mr. S. N. Dave, WES specialist, UNICEF, Kolkata, Mr. Sundarraj, Consultant, WES, UNICEF, Kolkata, and Prof. Anirban Gupta, Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, BESU, Howrah, to conduct the study is hereby acknowledged.

References

1. Fawell J, Bailey K, Chilton J, Dahi E, Fewtrell L, Magara Y. Human health effects: Fluoride in drinking water WHO drinking –water quality series. London: IWA Publishers; 2006. p. 29-35.

2. WHO. Chemical aspects. W.H.O. Guidelines for drinking- water quality. In: W.H.O. 3rd ed, Vol. 1. Geneva: W.H.O.; 2004. p. 184-6.

3. Susheela AK. Prevention and control of fluorosis: Dental fluorosis- symptoms. 1st ed. New Delhi: National Technology Mission on Drinking Water; 1991. p. 7-9.

4. RGNDWM. Prevention and control of fluorosis- health aspects vol. 1: Oral cavity, teeth and dental fluorosis. New Delhi: Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission, New Delhi: Ministry of Rural development; 1994. p. 53-7.

5. Susheela AK. Prevention and control of fluorosis: Skeletal fluorosis- symptoms. 1st ed. New Delhi: National Technology Mission on Drinking Water; 1991. p. 4-6.

6. RGNDWM. Prevention and control of fluorosis- health aspects vol. 1: Effects of fluoride on the bones, the skeletal system & skeletal fluorosis. New Delhi: Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission, New Delhi: Ministry of Rural development; 1994. p. 40-9.

7. Susheela AK. Fluorosis: An easily preventable disease through practice and intervention: New Delhi: Fluorosis Research & Rural Development Foundation; 2005. p. 10.

8. Fluorideandfluorosis.com [home page on Internet]. New Delhi: Fluorosis Research and Rural Development Foundation online resource. Available from: http://www. fluorideandfluorosis.com/fluorosis/districts.html. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 6].

9. Fluorideandfluorosis.com [Internet].New Delhi: Fluorosis Research And Rural Development Foundation online resource. Available from: http://www.fluorideandfluorosis. com/fluorosis/prevalence.html. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 10].

10. Choubisa SL. Endemic fluorosis in southern Rajasthan, India. Fluoride 2001;34:6170.

11. Bharati P, Kubakaddi A, Rao M, Naik RK. Clinical symptoms of dental and skeletal fluorosis in Gadag and Bagalkot districts of Karnataka. J Hum Ecol 2005;18:105-7.

12. Ruan JP, Yang ZQ, Wang ZL, Astrom AN, Bardsen A, Bjorvatn K. Dental fluorosis and dental caries in permanent teeth: Rural school children in high fluoride areas in the Shaanxi province, China. Acta Odontol Scand 2005;63:258-65.

13. Mann J, Tibi M, Sgan-Cohen HD. Fluorosis and caries prevalence in a community drinking above optimal fluoridated water. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1987;15:293-5.

14. Acharya S. Dental caries, its surface susceptibility and dental fluorosis in South India. Int Dent J 2005;55:359-64.

15. Kumar J, Swango P, Haley V, Green E. Intra-oral distribution of dental fluorosis in Newburgh and Kingston, New York. J Dent Res 2000;79:1508-13.

16. Narayana AS, Khandare AL, Krishnamurthy MV. Mitigation of fluorosis in Nalgonda district villages: 4th International workshop on fluorosis prevention and defluoridation of water; 2004. Available from: http://www.de-fluoride.net/4th proceedings/98-106.pdf. [Last cited on 2009 Aug 9].

17. Shashi A, Kumar M, Bhardwaj M. Incidence of skeletal deformities in endemic fluorosis. Trop Doct 2008;38:231-3.

18. Kubakaddi A, Bharati P, Kasturba B. Effect of fluoride rich food adjuncts and prevalence of fluorosis. J Hum Ecol 2005;17:43-5.

Kunal Kanti Majumdar

Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, KPC Medical College, Kolkata, India

Path Alias

/articles/health-impact-supplying-safe-drinking-water-containing-fluoride-below-permissible-level

Post By: Hindi