Of the one billion people defecating out in the open globally, 66% live in India of which as high as 92% live in rural areas. India still continues to lag behind in terms of achieving the Millennium Development Goals sanitation target to halve the population that doesn't have access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015, despite continued efforts by the government over the last three decades.

The paper titled 'Silencing caste, sanitising oppression: Understanding Swachh Bharat Abhiyan' published in the Economic and Political Weekly, argues that this has to do with the tendency to ignore the link between caste and sanitation and turning a blind eye to the deeply entrenched caste hierachies in Indian society that assign and expect one section of the society--the 'polluted castes'--to undertake tasks such as manual scavenging, unclogging manholes and cleaning the filth created by others.

The caste system is something absent in all the better performing countries in South Asia as compared to India which has more than 6.76 lakh people--95% of whom are women--engaged in manual scavenging, which includes “lifting and removal of human excreta manually".

Poor legislative support

Legislation has not been of much help either. The Government of India enacted the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act in 1993. However, it took four years to notify it in the Gazette of India (1997), and the majority of the states enacted it only by 2000. Evidence shows that in 20 years of its existence, not a single government official has been convicted for allowing this practice to continue.

Similar is the situation with the new legislation titled the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 (or the MS Act, 2013) in September 2013. The legislation views the provision of protective gear to the workers and observance of safety precautions as an alternative to mechanisation. According to the Act, those using protective gear and devices as may be notified by the central government would not come under the definition of a manual scavenger, which too looks like an escape clause that leads to continuing deployment of workers for manual scavenging.

Occupational hazards

The sanitation workers continue to suffer and face a number of occupational hazards besides having to face the indignity of spending numerous hours of their life lifting and disposing human faeces and cleaning sewers. Deaths are common among these workers, but continue to be underreported. The average lifespan of a manhole worker is about 45 years.

If a worker does not die inside a manhole but due to illnesses contracted while doing the job, then there is no adequate monetary compensation, which is anyway an insultingly meagre amount in the range of Rs 50. In developed countries, manhole workers are provided with proper safety equipment before they descend into the gutter. On the contrary, Indian sanitation workers wear loincloths or shorts.

This lack of sensitivity to the needs of the sanitation workers is also reflected in the lack of attention given to finding alternative means of managing garbage and sewage. No efforts seem to be made by urban planners, designers and technologists to conceive a human-friendly system of managing garbage and sewage. Instead, the tendency to rely on disposable, cheap, Dalit labour continues.

Issues related to caste and oppression are consciously ignored by communities and policy

The only explanation possible for this is that caste and related discriminations have become so common and ingrained in our psyche that nobody finds anything abominable about it. The origin of insanitary practices in Indian society can be linked to Hindu notions of purity and pollution, and with the caste system and the practice of untouchability and oppression of the 'polluted castes'.

The paper argues that these key issues however, continue to remain unaddressed in the implementation of the Clean India Campaign, and could lead to its failure despite the tremendous human as well as financial resources involved. Life stories of the sanitation/conservancy workers show the apathy of the rest of society towards their work, and are reminders of the fact that millions of people in this country who are equal citizens of the republic, are condemned to live a subhuman life so that the rest of the society looks clean.

It is thus high time that we acknowledge the contribution they make for our health and survival, at the cost of their own. Unless the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan acknowledges this connection between caste and sanitation, its goal of cleaning India will continue to remain a distant dream.

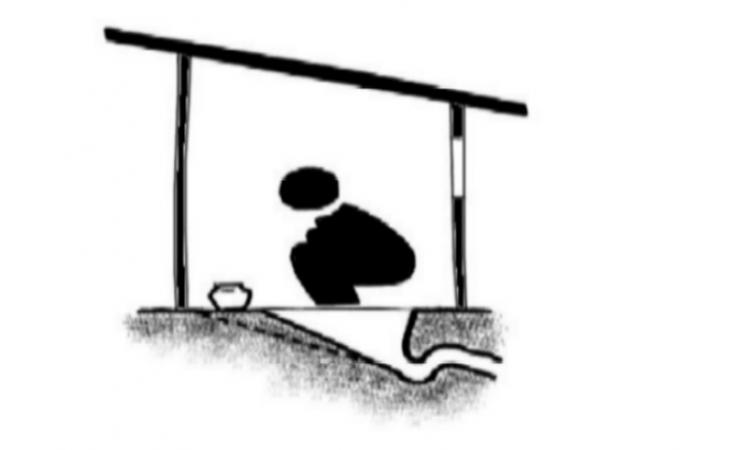

Lead image source: Sourabh Phadke in CONRADIN, K., KROPAC, M., SPUHLER, D. (Eds.) (2010): The SSWM Toolbox. Basel: seecon international gmbh. URL: http://www.sswm.info

Please download a copy of the paper below.

/articles/understanding-connect-between-caste-and-sanitation