Concurrent newspaper reports with contrary data points on the same subject is not unusual especially when it comes to issues on water. Some of these differences could get rationalized when we normalize for context but for the most part, we would not be able to tell which one is true because the data presented would mostly qualify as claims and not as facts.

What we mean here is that we would not be able to interrogate the data for integrity which creates an enormous amount of “dumb data” resulting in noise that is very difficult to interpret. Decisions taken on such data, therefore, tend to be tentative and in many cases, the response is to collect further data to ground truth existing data. Oftentimes, because of the diffidence with the data, it is not “opened” up for the public, and/or it is put up in formats that are very onerous to consume. Net, net the water sector suffers from a scarcity of facts.

One reason for this is that investment in technology is seldom looked at as strategic. It is mostly to support processes that literally replace paper forms at one end and generate limited use Management Information Reports (MIS) reports on the other. This is often done through programmatic and contractual arrangements between non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or government entities and technology partners.

These arrangements are usually limited in time (confined to the period of the program), purpose (mainly for programmatic compliance), and audience (mostly reporting upwards after the event).

While we see some of this data put out in the open as datasets and case studies, the ability to engage with this data outside the programmatic context is extremely limited, if not impossible. If we were to peg this frame to its generational counterpart in the for-profit space, we would probably find that it is more 90’s in its form and function. What will it take for the development sector to cover three decades and catch up with the advances in technology and leverage them for the public good?

We find that for data to have the best chance at driving purpose it should be open. And for open data to be effective, it should have some core characteristics.

[1] For starters, the data should be digitally verifiable. This means we should be able to prove who or what collected it - where, when and how. This is necessary to move data from the realm of claims to the realm of facts.

[2] For these facts to then be useful, the data should be consent-enabled so that we know what permissions it has and therefore, what uses it can be applied to. This is extremely important, especially in the development world where the trend leans toward ‘more data, the better’, which means we run into the danger of collecting personally identifiable information that can have very serious consequences if it finds its way into the open.

[3] Additionally, we should be able to see the chain of custody of the data so that we are certain that it has not been tampered with as it travels in the process chain.

[4] Lastly, we should be able to collect this data at meaningful units of change like the block or district and at saturation. It is of little use if the data is available for a few villages and at infrequent intervals.

It is indeed game-changing when we can see data with the above qualities. The trust in the data drives stakeholders to do more with it, and faster. It is liberating and the imagination gets triggered in powerful ways when you can double click on data and engage with it both at the disaggregated and aggregated level.

Here is an example of what that looks like for people, content, and artefacts in some of the work that our Government and civil society organization partners have done with our design and technology partner Socion.

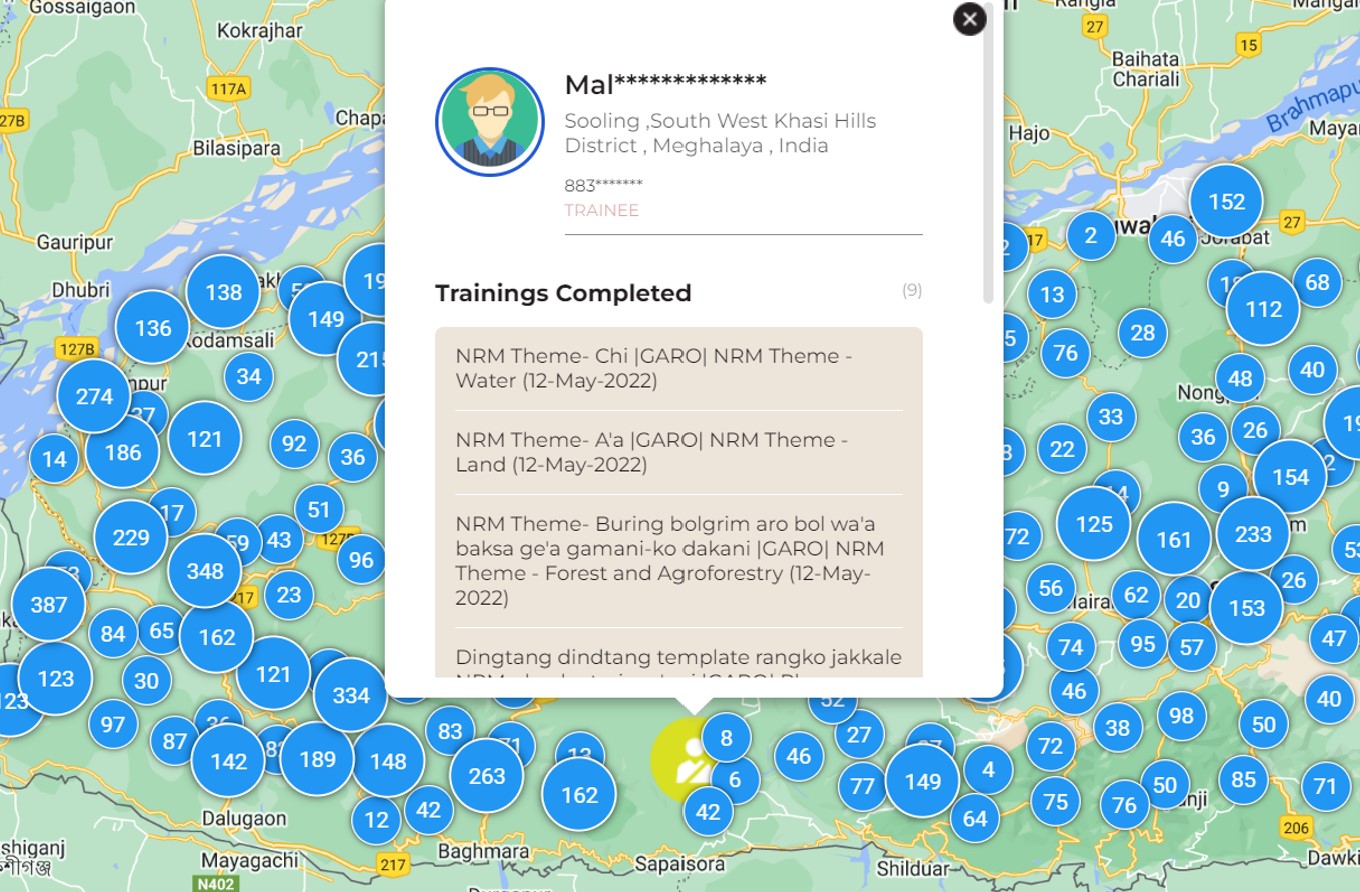

In the image below from a program in Meghalaya, we can see data of all the people trained in every village of the state. They have a digital footprint on the platform and the data on their training and location is available to the public if they want to locate such skilled people in the region. Keeping in view the core characteristics of open data, all personally identifiable information has been redacted. This information has not been manually entered but rather generated digitally during interactions which ensures chain of custody and trust in the data.

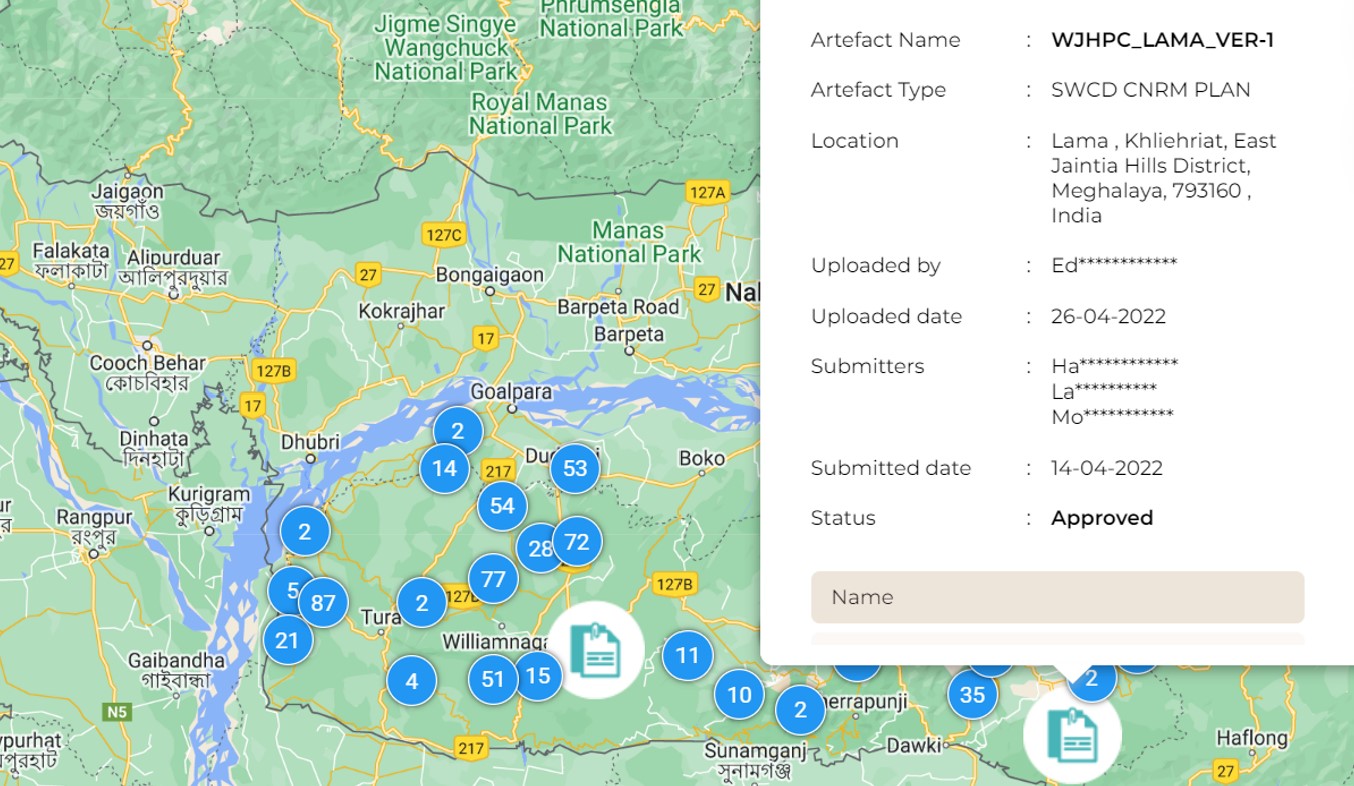

The same platform also provides public access to participatory plans which have been created by villages and contain data on village-level indicators, which have high re-usability.

Similar data is available across other geographies on this platform with open public access.

For this to happen in more places, we need to re-imagine how to use technology to capture signals as they happen - more effectively and efficiently. This will entail thinking through what tasks are performed, who performs them, and how will they be able to represent, with the least friction, that they have actually performed them.

Perhaps there may come a time when we will have sensors that will be available and affordable to pick up these signals, but for now, we have to configure this with what we have in abundance – people on the ground.

Once we have facts at scale and saturation, we can foresee an entirely new ecosystem coming together. There will be operating models that will very likely evolve for service providers to run these “facts” registries which can supply precious digital nutrients to developmental work. We can imagine a future with an organic progression toward better standards that can enable the use, re-use, and most importantly combinatorial use of such data. After all, we need water not for water’s sake but for health, livelihood, etc. We have not even scratched the surface of these intersections as we are struggling to make sense of these domains on their own.

The value to society will accrue only when we can work and solve problems at these intersections. We can look to developing a measurable unit of convergence across the ecosystem. At this point, it is difficult to compare, contrast or collaborate across initiatives as what is visible are differences in inputs, outputs, and outcomes. What we need is a common denominator across initiatives where we can see if we are a net contributor or a net consumer of the commons. Else we are all working in the hope that our work is adding up and while hope is essential, it cannot be a substitute for strategy.

The returns can be magical if we can collectively invest in this next gen thinking and execution. Are we ready for that?

The author is the CEO of Arghyam.

/articles/some-data-more-equal-others-power-double-click