If you visit Shimla during the summers, you will notice people being asked to use water judiciously. You will likely see tankers queue up around residential areas as the supply from the municipal corporation declines. Why would a hill station that is fed by mountain rivers and overlooked by glorious snow peaks face water scarcity?

Water and hills have a very intimate relationship. During the rainy season, heavy downpours fill up the natural lakes and ponds. In the winter, peaks are covered with snow, which form glaciers that feed the rivers and streams. But with growing population and weather fluctuations, availability of water has become uneven and unpredictable.

In Himachal Pradesh, for instance, precipitation is confined to only about three or four months in a year. This varies from about 600 millimetres (mm) in Lahaul & Spiti district to around 3200 mm in Dharamshala, Kangra district. During summers, the hills are parched as the flow in the rivers and streams reduces and tradtional sources also dry up. This makes it all the more important for those living in the hills to look for sustainable solutions like rainwater harvesting, wastewater recycling and groundwater recharge.

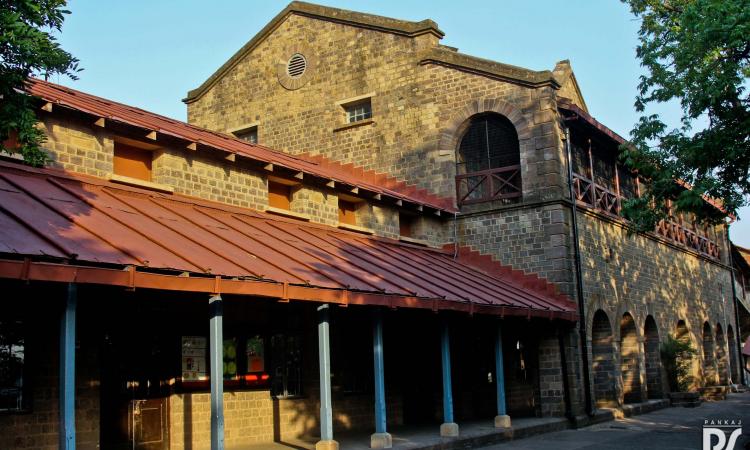

The Lawrence School at Sanawar in Solan district of Himachal Pradesh recently made an attempt towards achieving water sufficiency by recycling the sewage generated within its campus. A former army establishment, the school received most of its water, 60 kilo litres a day (KLD), from the nearby Military Engineer Services reservoir. However, the supply used to turn erratic during the summer months. The daily requirement of 182 KLD couldn't be met by this source.

So the authorities drilled three borewells to a depth of about 450 feet to 500 feet each in the school. Initially the discharge from these borewells was about 10,000 liters per hour but during the dry spell from March to June, it went down to 2,000 to 3,000 liters per hour. One of the borewells also stopped working. Other sources like natural springs dried up during summers while tankers carrying water from Pinjore would come at a high cost. The school was already doing partial recycling of water through a sewage treatment plant but that was not enough. The rainwater harvesting methods already employed also didn't yield great results as only partial roofs were covered and the supply remained erratic. There was an urgent daily need of at least 50,000 litres.

After some thought on the subject, the school authorities decided to raise the issue with their old students. Lawrence School is known for its famous alumni like Sanjay Dutt, Saif Ali Khan, Omar Abdullah, Sukhbir Badal, Ness Wadia and Maneka Gandhi among others. When they were called for help, the batch of 1983 came forward and collected Rs. 20 lakh to make their alma mater self-sufficient in water. One of the students, Sanjay Aggarwal, was given the responsibility to head the project. Aggarwal was the right choice because his Dehradun-based company, Clover Organic Pvt Ltd, had already been providing innovative solutions in the sanitation and agriculture sectors.

Aggarwal looked at various ideas including the drilling of another borewell, more rainwater harvesting and wastewater recycling. While no contractor was willing to offer assured supplies through new borewells, rainwater harvesting would have required all the major roofs of the school buildings to be covered and a contour map indicating various elevations of surfaces and possible flow of water to be created. The estimated cost of this was Rs. 2 crore. Thus, after careful evaluation, wastewater treatment seemed the most feasible option.

The school was already generating 64,935 litres of sewage. The needs of the school could have been met by increasing the capacity of the treatment plants. So a new sewage treatment plant with a capacity of 10,000 litres was set up near the girl's department, which generated 10,435 litres of sewage. Till then, only septic tank treatment was being used. Septic tank is mostly used in villages and old towns where there is no sewage system. It's an underground structure which holds the wastewater generated from toilets. The waste is decomposed over a period of time.

The school was already generating 64,935 litres of sewage. The needs of the school could have been met by increasing the capacity of the treatment plants. So a new sewage treatment plant with a capacity of 10,000 litres was set up near the girl's department, which generated 10,435 litres of sewage. Till then, only septic tank treatment was being used. Septic tank is mostly used in villages and old towns where there is no sewage system. It's an underground structure which holds the wastewater generated from toilets. The waste is decomposed over a period of time.

At Lawrence School, pipes to carry the sewage to the new sewage treatment plant and then to the recycling plant after treatment, were laid. Clover Organic also used NatureVel, a solution containing 10 different microbes. This solution recycled/cleaned the water by reducing biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), total dissolved solids (TDS) and increased levels of dissolved oxygen. This was used in all the treatment plants by the school. The already existing two treatment plants were also repaired and made more efficient.

The school has now started receiving more than 38,000 litres of recycled water daily, which is being used for gardening and flushing. This has freed up fresh water of equal quantity thereby making the institute water surplus. It is now planning to add one more treatment plant for future needs and is also looking at how to minimise the cost of rainwater harvesting.

The Lawrence School was lucky to have alumni, which raised the necessary funds and also provided guidance. This successful effort shows that residential institutes can become self-sufficient and lead by example if they know how to utilise their resources - human as well as capital.

This article is an abridged version of a paper that was submitted by the authors for the Sustainable Mountain Summit (Kohima September 25 - 27, 2013). The full paper is attached below.

/articles/sanawar-school-makes-good-use-its-sewage