Decades of skating over environmental concerns have clearly cost us dear. The folly of pursuing better crop yields using chemical fertilisers in an indiscriminate manner has been surfacing lately. “Decades of agricultural abuse using fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides have taken its toll on us. We have been shooting ourselves in the foot by doing it,” says Raman Tyagi, director of Neer Foundation, a Meerut-based nonprofit working on water and agriculture. They not only kill our soil and threaten the farms but also impose a huge subsidy burden on the government.

The sorry state of soil

“The decline in soil quality in our country is the result of inappropriate management practices adopted over decades. As far back as in 1928, the Royal Commission on Agriculture had observed that soils in India had reached a condition where no further decline in quality was expected,” says Dr I. P. Abrol, an eminent soil scientist and former deputy director general of the Indian Council of Agriculture Research.

“Yields have become stagnant. More external inputs are required to keep it going,” says Tyagi. This is not a sustainable agricultural practice. Tyagi believes soil erosion and loss of agricultural biodiversity are widespread due to this.

A quick indicator of the soil quality is its organic matter. Stressing its significance, Abrol says, “The organic matter is an essential component of soil for a healthy ecosystem including production functions. Many of the important functions of the soil depend on the biological activity, which in turn, depends on the amount and nature of organic matter regularly returned to the soil. Application of fertilisers results in enhanced biomass production and therefore more addition of organic matter through roots. However, excessive application of fertilisers is likely to adversely impact biological activity in soils.”

“The decline in the quality of the soil is mainly due to the decline in the organic matter content of soils from clearing forests for agriculture. The decline has also been accentuated by the limited availability of farmyard manure and its reduced application on soils since the mid-20th century,” says Abrol. “In Meerut, it was a common practice to grow succulent green manure crops such as dhaincha (Sesbania aculeate) which supplemented soil nutrients,” says Tyagi.

Some farmers have realised the importance of organic matter and have begun restoring their farmlands through natural methods. The government on its part, however, introduced the nutrient based subsidy scheme in 2010 for better soil health. The scheme wasn’t very successful. The central government, in 2015, came up with a soil health card for farmers to help restore the health of their soils.

The new soil health card turned out to be nothing but a modification of an old scheme already operational in the country called the National Project on Management of Soil Health and Fertility introduced in 2008-09.

This time around, however, the scheme had a greater outlay with the government allocating Rs 568 crore. A press information bureau release called it a flagship scheme that is a model for agricultural revolution. This is an offshoot of a scheme introduced in Gujarat in 2005. Though there is not much research to validate its impact, case studies point towards its success. An isolated research study by J. Makadia, Navsari University states that the scheme “led to a positive and significant impact on per hectare yield of selected crops. Generally, with soil health card, farmers utilised fertilisers judiciously as per the recommendations”.

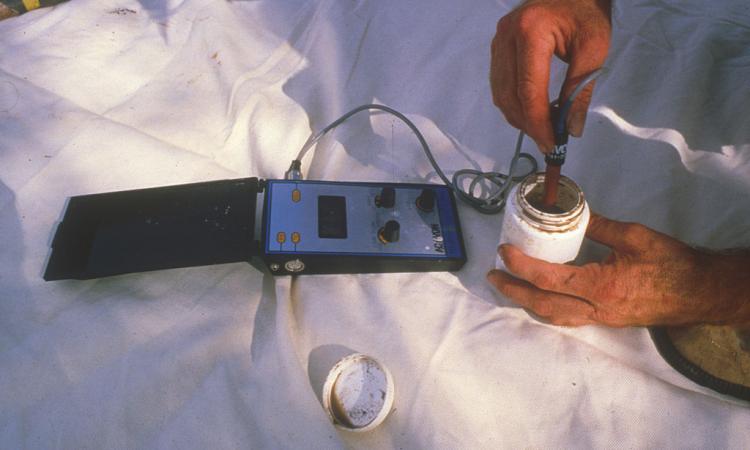

As per the new scheme, soil cards are being issued to all 14-crore farmers in three years with crop-wise recommendations of nutrients and fertilisers required for the individual farms. The idea is to improve productivity through judicious choice of inputs for better crop yield. To prepare the card, soil samples are collected from individual farms and tested by experts in various soil testing laboratories. The experts will analyse the strength and weaknesses (nutrient and micronutrient deficiency) of the soil and suggest measures to deal with them which will be displayed on cards. Though the concept sounds good, the government plans to spend only Rs 568 crore for 14-crore farmers that amount to just Rs 40 per farmer.

What is the outcome of this measure?

As per a report by Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative Limited, the “effort to issue soil health cards to every farmer in the country by 2013 was progressing well in Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat but major eastern states of Bihar and West Bengal have been lagging behind so far”.

The numbers of soil health cards have surged since the new scheme was launched but the user experiences vary. Some like M. G. Reddy of Settipalli village of Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh were in for a pleasant surprise. He says, “After applying nutrients as per recommendations of the soil health card, my paddy yield increased by 170 kg per acre.” As per his soil card, he was advised to reduce the application of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, increase farmyard manure application and add biofertilisers at the rate of 2 kg per acre. “The recommendations were of great help and I was able to save about Rs 3000 per acre,” he says. This is exactly what the scheme was envisaged for–-guide the farmers to use fertilisers judiciously, improve soil health, increase soil organic carbon, maintain favourable pH and water holding capacity of the soil.

Despite some positive responses to the card, the card alone won’t ensure balanced fertiliser use. Besides, the card does not guarantee farmers’ compliance. “When the soil health card scheme was launched in 2015, Neer Foundation supported over 100 farmers from Meerut district to get their soils tested at the district laboratory. To test the authenticity of the results, we sent the same sample to the laboratory in four different packages and got completely dissimilar results,” says Tyagi who believes the scheme is a hoax.

Some farmers like Hukum Chand from Jhalawar district, Rajasthan does not understand what the advisory says. His soil was tested at a government laboratory two years back with support from a Jaipur-based nonprofit, Indian Institute for Rural Development. He is not aware that the card will be renewed every three years as the soil nutrient levels keep changing.

“There is a dearth of funding, manpower and laboratory facilities with the agriculture department,” says Tyagi. “However, the soil tests done by Indian Farmers Fertilisers Cooperative Limited and Krishak Bharati Cooperative Limited are sound. These organisations have the requisite equipment to test pH levels, nitrogen, phosphorous, potash content and micronutrient and have experienced manpower,” he adds.

A way out beyond monitoring

Abrol believes that though the nutrient status of the soil is important, that alone will not ensure better productivity. Equally important are improving and monitoring the carbon status of soils and the state of soil biodiversity which will improve the soil function. “I feel a lot more clarity is required in respect to how soil health card scheme will help. Available nutrient status of soils, though important, is in no way indicative of the state of soil health. As of now, this appears to be the primary objective,” says Abrol.

Chand says for the advisory on the card to be implemented by the farmers, agricultural extension services, like communication and learning activities, need to be stronger. “Schemes like these are poorly designed and inconsistently managed and are of no help to farmers. What is needed instead, is proper agricultural extension service through which farmers are taught about the application of knowledge to agricultural practices,” Tyagi concurs.

Another hitch is the cost effectiveness of the scheme. The laboratory analysis of soils is an expensive, time-consuming process and cannot be done properly on a budget of Rs 40 per farmer. What we need is farmer-based evaluation regarding soil management practices and their effects. A recent study by Islam et al from Bangladesh suggests that monitoring of soil quality using a convenient tool is important.

What took centuries to be impaired cannot be repaired in a short period of three years. The state has to go beyond monitoring to proactive support to farmers through its extension system to adopt sustainable agriculture. Abrol shares how research is validating natural methods of soil restoration. His message is simple: “Regular additions of organic matter to the soils should be best done by leaving the crop residues in the field. Decomposing plant residues enhance the soil’s biological activity which, over a period of time, improve organic matter status of soils. Globally, farmers are increasingly adopting no-till farming. Indian agriculture has to catch up with it fast.”

/articles/playing-soil-health-card