Like many small seasonal rivers in India, the Naagin River (East Kaali) is unidentified on Google Maps; however, it is still alive in the collective memory. There are scriptural and folk song references marking the religious and cultural importance of the river. The river originates in Antwara, a village in Khatauli Tehsil of Muzaffarnagar District, Uttar Pradesh. It snakes through seven districts, including Meerut, Hapur, Bulandshahar, Aligarh, and Kasganj, and is confluent with the Ganga at Kannauj after covering almost 550 km.

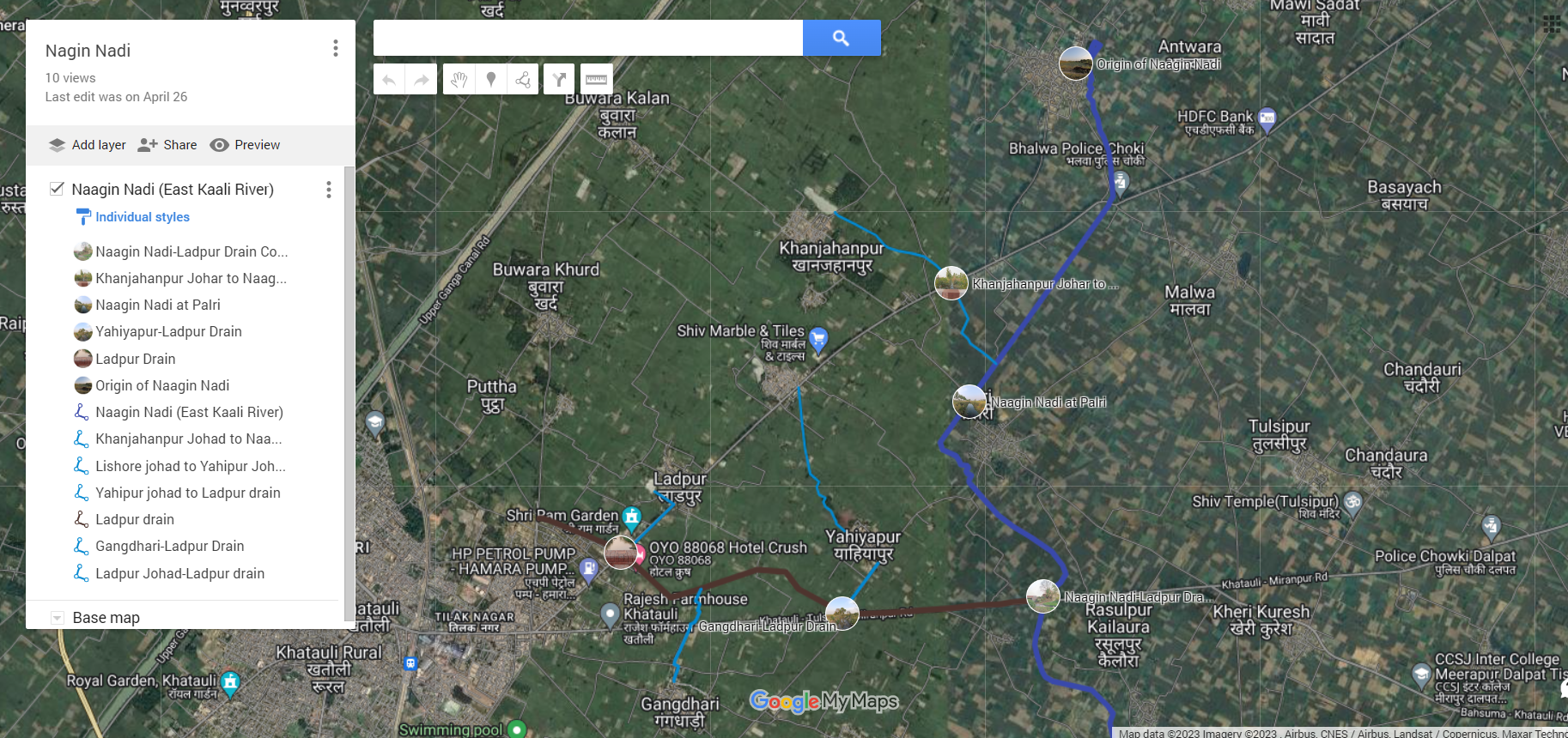

The river receives sewerage and industrial effluents from more than 94 industries (mainly sugar mills, paper mills, textiles, distilleries, and slaughterhouses) located in these districts and finally turns into poison. The disposal of industrial effluents and sewerage begins within five kilometres of the river’s origin at the Sugarmill situated in Khatauli via the Ladpur drain (figure below).

Ecological history of the river

The river originates in a low-lying area of the region with a high groundwater level. The river used to be a perennial river that got fed by excessive groundwater and monsoonal discharge from the region. A network of village ponds (Johads) with the river used to work as flood management during the monsoon. The johads of the adjoining villages feed into the river (figure below depicts the network of the johads), in addition to the excessive water from the irrigation network of the Upper Ganga Canal. Hence, the river was the way out of the excessive water in the region, enabling access to the low-lying land for intensive agriculture and protecting the settlements from flooding.

Residents from Antwara mentioned that the water used to be in the river all year, and during monsoons, the river used to flow up to 500 m wide. In the last forty years, the river has transformed into a seasonal one because of the considerable reduction in groundwater and rainfall. One of the villagers (a 77-year-old farmer) recalled that rainfall was heavy thirty years ago, and now both the intensity and frequency have reduced significantly.

Furthermore, post-Green Revolution, the extensive groundwater abstraction in the region for the production of water-intensive crops, primarily sugarcane, led to not only a reduction of the water table but also pollution due to excessive use of fertilisers, pesticides, and insecticides. The Naagin basin used to have a water table almost at the surface, and that’s why the river was perennial.

Another reason for the current plight of the river is also attributed to the deforestation and extensive plantation of non-native species such as Eucalyptus and Poplar (Cottonwood). The increase in population and pollution have also contributed to the killing of the river. Lastly, the insensitivity and indifference of the common masses have arguably caused the plight of the river.

Rejuvenation work at the origin

Recently, the river attracted the attention of environmental and river activists, particularly the Neer Foundation based in Meerut. The foundation has been engaged with the cleaning of the Kaali River (as this river is also known) in the Meerut district for many years. However, when they looked for the origin of the river, they failed to find one.

Raman Kant, the director of the Neer Foundation, popularly known as Nadiputra (the son of the river), narrated how hard he tried to find the source of the river with the help of the irrigation department and scriptures, a reference in a holy book of the Shri Nangli Sahib (Figure 3). However, in 2018, when he reached the origin of the river, he failed to find it as the land of the river had been encroached on and used for cultivation for more than twenty years at the origin and fifty years in the forest land.

After struggling for three months, with the help of the villagers, the rejuvenation of the river began in 2019. The 22-kilometre stretch of the river was revived and cleaned up under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. Its success story was also featured in the eighth episode of season 2 of Rag Rag Mein Ganga, a travelogue by the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) and Doordarshan.

The work came to a halt because of the elections, land dispute, lack of support from the local administration, and local political unwillingness and funding. For more than one year, no work was undertaken, and the river’s land got encroached on again. The reservoir that was developed to mark the origin has undergone extensive eutrophication (lead image at the top).

The Neer Foundation informed us that a plan is in the pipeline for the river and will begin to work out soon. One of the proposals is to bring 110 cusecs of excessive water from the Upper Ganga Canal to give the river a perennial outlook and dilute pollution. Further, there is a need to remove around 25 electric poles from the pathway of the river and develop a wetland ahead of the river for checking the wastewater from the village.

Way forward

To bring the additional water to the river without addressing the industrial inflow into the river seems like a superficial and temporary fixation on the issue. Also, the ongoing, unchecked groundwater abstraction turns out to be the major culprit and requires attention. The encroachment of the river, forest, and johad land needs to be removed and the lands revived.

The story of Naagin Nadi resonates with many seasonal small and intermittent rivers that play a crucial role in the flow of major rivers such as the Ganga, Cauvery, or Godavari, hence, substantial attention must be paid to their restoration and rejuvenation. Lastly, rather than being reactive, both the administration and society must be proactive with their actions.

Author: Ritika Rajput is an independent researcher. She holds a post-graduation in Ecology and Environment Studies from Nalanda University, Rajgir. Previously, she was a fellow at the Indian Smart Cities Fellowship, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (2021-2022) and an urban fellow at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (2020-2021). Email: ritikarajput3797@gmail.com

/articles/perennial-seasonal