Guest post: Amita Bhaduri

West Delhi’s dusty neighbourhood, Shadi Khampur now has its own museum, in the traditional brick-and-mortar sense. I live nearby, have worked out of an office here and am familiar with the alleyways. But I got to know only now, what life in the neighbourhood was like. Its rich history and its connect to larger narratives from the past, like the series of land acquisitions in Delhi, the Emergency, and the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 which had gone largely undocumented and unarchived have been chronicled in the Neighbourhood Museum of Local History of Shadi Khampur, at Studio Safdar, a cafe cum bookstore.

Neighbourhood Museum at Studio Safdar

Source: Facebook page on “Public Art Project at Studio Safdar”

The Jana Natya Manch (Janam), the theatre group that set up Studio Safdar in the locality in April 2012 has along with the Centre for Community Knowledge at Ambedkar University Delhi put together artefacts, old photos and maps, everyday objects and audio playback on Shadi Khampur. The museum covers over five hundred years of its history. Scholars have attempted to engage with the city’s neighbourhoods in an attempt to dispel the notion that the city is a site of magnificent and opulent monuments.

Janam’s teams interacted with the communities as to how long they had been here, their history etc. The exhibition also displays some old and new photographs of the area that describes its transformation. A radio box from the 1960s and a nagada (kettle drum) used in the weddings in the area are some of the key artefacts that have been displayed.

Shadipur and Khampur are two distinct villages adjacent to each other but are often clubbed together as Shadi Khampur to distinguish it from the other Khampurs in the city. The setting up of Khampur village was followed by that of Shadipur. In fact, Shadi Khampur now includes the settlements of Ranjit Nagar and Guru Nanak Nagar as well.

The project attempts to give an account of the living urban habitation and its specific characteristics, as embedded strongly in people's minds. The way the urban spaces of its narrow lanes have grown is really fascinating.

Delhi’s growth since the 10th century has not been outward from a single urban center but various rulers have created new forts and townships with the result that there were several Dillis. This shifting of the urban center left many urban/ sub-urban and rural settlements, which after Independence were left untouched and given the special status of “urban villages” within planned Delhi. Shadi Khampur is one such urban village that has become denser and is faced with real estate pressures with the metro coming up right next to it.

The area was agriculture based and has been undergoing ‘urban renewal’ since the last few decades, and has a migration tale to tell. During the 1940s the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) acquired land over here as they had to shift their campus from Samastipur (Pusa) following the Bihar earthquake of the 1930s. This was followed by a succession of land acquisitions for developing industrial and residential pockets like the Delhi Milk Scheme plant, the Delhi Transport Corporation Shadipur Depot, Swatantra Bharat Mills etc.

“These also brought in workers from other places, besides providing employment to the locals”, says Sudhanva Deshpande who has conceptualized and curated the museum. Sikh families also moved here following the partition. The XYZ block is dominated by Muslims, who were resettled here following their evacuation from Turkman Gate area in 1972 supposedly to ‘beautify’ Delhi. This ‘resettlement’ colony where many residents trace their roots to Rajasthan and Haryana is truly a melting point of various cultures and is now home to migrants from Kerala, Orissa, Bihar and western Uttar Pradesh.

Inauguration of Neighbourhood Museum at Studio Safdar

Source: Facebook page on “Public Art Project at Studio Safdar”

It became evident while the project was being designed that while the area does not have monuments like some other areas of the city, it has several wells that have been built over. The studio has an artefact titled “Wells of Shadi Khampur”. It says that in the days before partition, there were many big and small wells used by different communities. Nearly all the wells have been filled in or built over. Some had sweet clean water and were called ‘bhamakua’. Shadipur had at least four big sweet water wells, which according to some was the reason why the place was chosen for the IARI. The one that survives has been closed with an iron grill after someone committed suicide in it. The well is still worshipped at weddings and the birth of a child.

There were some wells in the fields and some in the village itself which were used for irrigation and washing. Across Patel Road, behind the present Punjab National Bank (PNB) there was a johad (water body) near a pipal tree, which still stands. That area was non arable land. The hard, brackish water was used for cattle. The Valmiki community used this water as they were not allowed to climb the steps of the village sweet water well.

The watering well (panghat) of Khampur was located behind what is now the police station, and water drawn using bullocks. For drinking water, like in most of Delhi, hand pumps gradually replaced wells. The municipal water supply came in the 1960s.

“Water ways” by Sohail Hashmi

A number of events are being organized in the Neighbourhood Museum to explore the many aspects of the history of Delhi. The first of these was an illustrated talk entitled 'Water ways' by Sohail Hashmi, on Friday 4th January, 2013. Sohail Hashmi studied geography, made documentaries, conducts heritage walks, writes, travels, cooks - and talks about all of these. He is also one of the founders of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT).

His talk looked at the seven cities of Delhi, how they met their requirements of water, the contribution made by the drainage system of the Yamuna and other traditional sources of water in meeting these requirements. This illustrated talk by him woven around photographs of the city's step wells, reservoirs, natural water bodies and canals built during the thirteenth to the eighteenth century located the traditional water bodies within the socio-cultural milieu of the seven Delhis and looked at lessons we can draw for the present.

His lecture dealt with these fortress cities of Dilli that had elaborate water bodies which included wells, step wells, water tanks etc., and that played a vital part in meeting the drinking water needs of the residents. Attention was drawn to the physiographical aspects of the land around Delhi, particularly the hilly prominences of the Aravallis which were home to a number of tributaries that fed the river Yamuna. In the north there were two big lakes apart from a river called Sahibi, formerly identified as Rohini. The river used to flow where the present sub-city of Rohini is located.

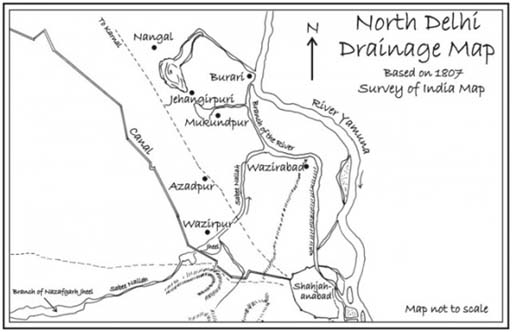

He noted that in 1807 when this Archeological Survey of India (ASI) map was prepared the flow in Sahibi river was almost over. This was because of an earthquake which changed the lay of the land. Sahibi used to drain in a lake which is estimated to have an area of 232 sqkm at full level. However, at that time all the other streams including the one starting from the south of Khanpur, at Saidulajaib, passing through Khirki, Chiragh Dilli, behind Nizamuddin and to Barapula were flowing. Over half a dozen natural streams joined at the Barapulla bridge built by Jehangir near the present Nizamuddin railway station. These have disappeared now.

North Delhi drainage map based on an 1807 map of the drainage of Delhi, made by a British cartographer

Image courtesy: www.kafila.org

As regards the first two Dillis, Hashmi noted that Mehrauli relied on water bodies like Hauz-e-Shamsi built by Altamash and the Naulakha Nala as well as other streams which emerged from the ridge to meet its water needs. The Hauz-e-Khas built by Ala-ud-Din Khilji was fed by a couple of streams both perennial and seasonal, some running through the present IIT campus. Ibn Battuta, who was in Delhi during this time, describes the scale of Hauz e Khas: one mile by two miles. These streams were collected in the depression to meet the water requirements of the garrison town at Siri. The water which flows down from Mehrauli through the present Aurobindo Marg, was directed into the Hauz. The stormwater drain system of the present days drains straightaway to the Yamuna. The area faces serious problems every monsoon.

Hauz e Khas

Photo courtesy: www.kafila.org

The other two Delhis namely Al’a-ud-Din Khilji’s Siri, and Mohammad Bin Tughlaq’s Jahanpanah were located in the plains. All these Delhis except Tughlakabad depended on the water bodies. The Tughlaqabad fort was built on the Aravallis using the lake as a moat. The fortified city depended on kunds, baolis (wells, step wells) natural and manmade lakes and on the streams that fed the Yamuna and not on the river itself as it was fairly far. The peasants who lived outside the fortified cities depended on the streams. Some of these water bodies were believed to have miraculous healing powers.

Hashmi’s lecture presented how the traditional water harvesting systems of the city were not only water carriers but also imprints of histories, traditions, and cultures. The natural flows were taken into consideration while planning the fortified areas and towns.

The lecture ended with the call for a bout of restoration of these much abused water bodies and of protecting the river Yamuna which is being subject to large scale destruction, dumping and encroachments.

/articles/exhibition-studio-safdar-shadi-khampur-traces-history-urban-village-and-its-water-systems