For almost two decades, the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act of 1993 was a paralytic occupant of the statute books. The Act prohibited the construction of dry toilets which required faeces to be removed manually and outlawed manual scavenging. Despite the provisions, the inhuman practice continued with no convictions been made in its 20-year history. And, the biggest culprit--the Indian Railways--was left out of its ambit.

In 2003 and again in 2013, the human rights organisation Safai Karamchari Andolan filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court seeking strict implementation of the 1993 law prohibiting manual scavenging.

Relentless campaigns and repeated nudges from the apex court resulted in an updated Act being passed by the Parliament in 2013.

Relentless campaigns and repeated nudges from the apex court resulted in an updated Act being passed by the Parliament in 2013.

Unlike its 1993 predecessor, the provisions of the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act 2013 extends to the Railways and cantonment boards as well. Offences were made non-bailable with a maximum penalty of five years of imprisonment and/or a fine up to Rs 5 lakh. The updated act also made the construction of sanitary community latrines for the railway passengers and staff mandatory within a period of three years from the date of its commencement.

Bacteria to the rescue

We are most familiar with the toilets that dump excreta directly onto the tracks. Apart from being an eyesore, faecal matter discharged directly corrodes the tracks, making maintenance a more tedious and costly affair. The Railways has been experimenting with a range of designs and technologies. Control discharge toilet systems (CDTS) has also been tried out where the toilet chute opens out only when the train reaches speeds of 30 kmph or above. While CDTS ensure cleaner stations as trains slow down as they approach, excreta is discharged on the tracks all along the way when the train picks up speed. The Railways has also tried out high-end vacuum toilets on an experimental basis.

Out of all these, bio-toilets emerged as the unanimous winner for large scale replication. An MoU signed with the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) in 2010 cemented Indian Railways' metamorphosis conclusively.

The DRDO initially ideated and designed biotoilets for the Indian Army's use in high altitude posts such as Ladakh where human excreta disposal was becoming increasingly challenging. Scientists identified bacteria capable of feeding of excreta while withstanding temperature extremes.

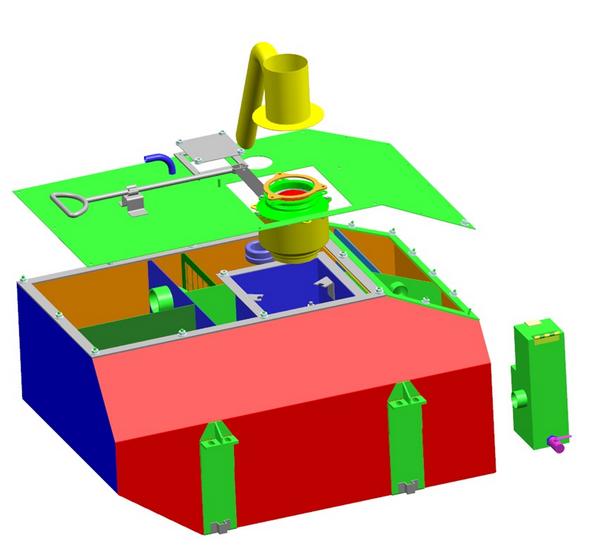

The design was tweaked to meet the demands of the Railways. The upgraded models come equipped with a colony of anaerobic bacteria, kept in six chambers underneath the lavatories, which convert human waste into water and small amounts of methane and carbondioxide. While the gases are released into the atmosphere, the disinfected liquid waste is discharged onto the tracks after chlorination. A premier hybrid vacuum version is also being tested out. A working prototype combining the principles of bio-toilets and the aircraft-like vacuum seal latrines has been installed in the first AC coach of the Delhi-Dibrugarh Rajdhani Express.

Relying on the inherent power of bacteria to gobble up excreta, bio-toilets present a seemingly simple, but extremely effective solution to the age-old inconvenience of discharging human faeces on the rail tracks. The effluent is odour-free, the process requires minimum human intervention for regular functioning and helps minimise track corrosion to a large extent.

Cautious optimism

India's first zero-discharge green corridor was launched recently by railway minister Suresh Prabhu in the 114-km stretch between Manamadurai and Rameswaram in Tamil Nadu. All trains plying on this route have been fitted with bio-toilets--a total of 1041 toilets in 276 coaches.

Given the great distances trains originating from the south traverse and the high traffic-density, Southern Railway holds the maximum number of coaches and has done well to fit 3861 toilets in 1255 of its coaches. The plan is to fit all 55,000 rail coaches owned and operated by all 16 zonal Railways across the country with bio-toilets by 2019, two years ahead of the initial deadline.

The director of NGO, CHANGE India, A. Narayanan, braces the topic with guarded optimism. While he lauds the Railways for undertaking an eco-positive step, he remains unsure whether the organisation should embark on such a gargantuan task before thorough performance and outcome analyses. "We cannot deny the fact that the Railways’ track record of introducing systems to eliminate manual scavenging has been poor in the past. It would make sense to conduct technical audits and validate the performance of bio-toilets before spending colossal amounts on expanding it to the entire fleet," Narayanan asserts.

He also throws up the question of maintenance. Since the functioning of these bio-variants are entirely dependent on the health of the bacterial inoculum, how can optimum functioning be ensured? Can these toilets handle the usual suspects--disposable plastic bottles and sanitary napkins?

Blocked and tackled

Chief rolling stock engineer (coaching) at Southern Railway, T. Venkata Subramanian responds reassuringly. "All the bio-toilets are purchased from DRDO-authorised vendors with whom we have inked annual maintenance and operation contracts (AMOC). AMOCs have also been signed with organisations which possess the necessary technical expertise to maintain these toilets. Once a train reaches the maintenance depot, the bio-toilets experts will ensure that all the units are up and running by the time the train rolls out of the yard."

Maintenance is carried out in accordance with the Railways' apex standards body, the Research, Designs and Standards Organisation (RDSO). A strict protocol has been put in place for quality control. Discharged liquid waste samples are sent to government-accredited laboratories on a regular basis to analyse a host of physical and biological parameters such as pH, total solids, COD and coliform levels.

A joint working group on bio-toilets was specifically set up to delve into various aspects of design and maintenance with expert members from the DRDO, RDSO and the Railway Board. The group meets every three months to go over the results of internal audits and analyse passenger complaints.

Technical challenges aside, support and co-operation from passengers is imperative for the success of this initiative. Audio-visual messages and information stickers regarding bio-toilet use is on the rise, both in trains and stations. Despite all this, many units come back clogged. "Conservative estimates suggest that 20 percent of the toilets come back to the yard faulty. But the rest make it back in one piece. That's something we need to focus on. We cannot go back to discharging faecal matter on to the tracks," points out Venkata Subramanian.

Change in people's attitude is indispensable and the seed needs to be planted while young. Sanitation and hygiene education should form an important part of school syllabi in addition to it being reinforced at homes. Given that popular media can make or break an enterprise, it would bode well for the Railways to rope in celebrities like Vidya Balan--who managed to turn around the country's rural sanitation campaign--to take their initiative to the masses. And, Venkata Subramanian is right to point out that people would rather have filmstars talk to them about sanitation than railway engineers screeching on about how to use bio-toilets.

While the 2019 target for eliminating all direct discharge latrines may seem incredulous, with its tough troop of bio-toilets and bio-vacuum toilets, the Indian Railways seems to be on the right track.

/articles/bio-loos-track-railways-clean-its-act