What is the state of water in India?

India has 18 percent of the world’s population, but only 4 percent of its water resources, which makes it among the most water-stressed in the world. A large number of people in India are now facing high to extreme water stress, informs the report by the government’s policy think tank, the NITI Aayog (World Bank, 2023). The recently published World Resources Institute's Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas warns that India is one of the top countries that could face extreme water stress in the coming years which could impact agricultural production and disrupt the economy stressing for the urgency to manage water resources sustainably in the years to come.

The NITI Aayog report predicts that the country’s water demand will be twice that of the available supply by 2030, affecting a large section of the population and leading to around 6 percent loss in the country’s GDP. As per the report of National Commission for Integrated Water Resource Development of MoWR, the water requirement by 2050 in high use scenario is likely to be a 1,180 BCM, whereas the present-day availability is 695 BCM (NITI Aayog, 2018).

Most of the agricultural production in the country is rainfed, meaning it is heavily dependent on the monsoon, which is increasingly getting erratic. Droughts are becoming more frequent and India’s rain-dependent farmers are already facing a crisis with 53 percent of agriculture in India being dependent on the rains. Groundwater resources that account for 40 percent of the water supply, are being depleted at unsustainable rates. Worse still even the water that is available stands the risk of contamination leading to nearly 200,000 deaths each year (NITI Aayog, 2018).

Conflicts over water sharing often increase among the Indian states in times of water scarcity, pointing to the fact that frameworks and institutions that are in place for water governance need to continuously evolve with time to take care of the water needs of the growing population under emerging challenges such as climate change (NITI Aayog, 2018).

Why is there a need for discussion on the water policy?

Effective policymaking is one of the key principles to achieve good governance. Policy includes guidelines that can help to take decisions and achieve rational outcomes. It is a statement of intent implemented as a procedure or protocol. Governments and institutions have policies in the form of laws, regulations, procedures, administrative actions, incentives and voluntary practices. Many a times, resource allocations mirror policy decisions.

Policy making is extremely important for management of water resources in India. This is because while physical scarcity of water persists in many parts of India, there are many cities and towns where the cause of scarcity is also mismanagement of water resources.

Decision-making in water resources is challenging because of their diverse nature and interdependence with other resources and requires involvement with multiple actors and institutions making it more complex and challenging (OECD, 2016). There should be a proper balance for water usage among humans and the environment. Framing water policies at the national, state, or sub-state levels are very important to maintain this balance (Rathee and Mishra, 2021).

Efforts have been made by several government agencies for water resource management by incorporating the 1st national water policy in 1987 and making amendments in it over time to encourage optimum use of water and lessen the burden on the environment (Rathee and Mishra, 2021)..

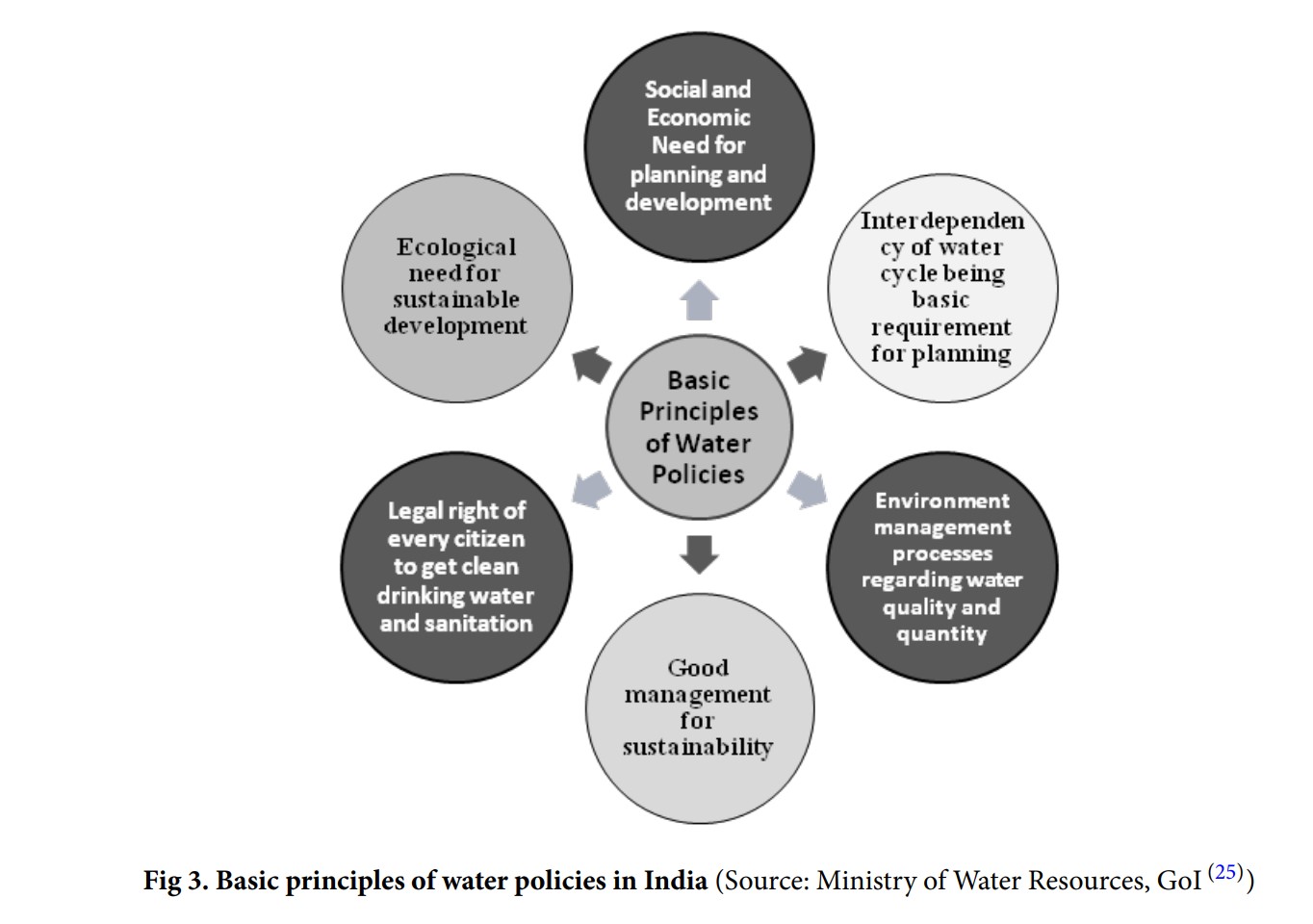

What are the principles on which water policies in India are based?

(Image Source: Rathee, R.K., Mishra, K.S. (2021) Water Policies in India: A critical review. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 14(47):3456-3466). The paper is open access under cc license.

How did the water policy evolve since precolonial times?

Precolonial times

The relatively high availability of water in India led to lack of attention towards water regulation during precolonial times (Cullet, P. and Gupta, J., 2009).

Colonial times

The concept of government control over surface waters started since the colonial period. The control over water and rights to water were regulated through the introduction of common law principles during the British rule that emphasised the rights of landowners to water. Riparian rights allowed a landowner to use surface water on his or her land while having the unlimited right to access groundwater on their land (Cullet, P. and Gupta, J., 2009).

Laws to protect and maintain embankments and to acquire land for embankments were also enacted during this period and the Controller was entrusted for implementing such laws. Other laws passed included regulation of canals for navigation and levying taxes on the users, river conservation, and rules on ferries and fisheries. The Northern India Canal and Drainage Act (1873) regulated irrigation, navigation and drainage and recognised the right of the Government to ‘use and control for public purposes the water of all rivers and streams flowing in natural channels, and of all lakes’ (Preamble). This led to the strengthening of state control over surface water and weakening of people’s customary rights (Cullet, P. and Gupta, J., 2009).

Colonial legislation also introduced a division between Centre and state in terms of responsibilities regarding water. The states or provinces were empowered to take decisions on water supply, irrigation, canals, drainage and embankments, water storage and hydropower under the Government of India Act (1935) and conflicts between provinces and/or princely states were subjected to the jurisdiction of the Governor General (Cullet, P. and Gupta, J., 2009).

More details on the history of evolution of water laws and policies in India can be accessed here

Postcolonial

|

Events that led to the Water Policy 1987

(Table source: Gupta, M. and Biswas, R. (2021) Structuring of water policies in India: An overview, Nagarlok, Vol LIII, Issue 4, 42). Nagarlok is a quarterly open access journal. |

National Water Policy, 1987

The first National Water Policy, 1987 aimed at increasing the area under irrigation, food output from 150 million tons in 1987 to 240 million tons in 2000, meet the drinking water needs of 100 percent of the population, and meet the sanitation needs of 80 percent of urban and 20 percent of rural populations. The policy document also highlighted the need to utilise groundwater, control floods, minimise impact of droughts, eliminate water pollution, establish a standardised National Information System, introduce a scientific planning and development procedure for water resources, establish Farmer Managed Irrigation Systems, etc (Paranjpye, V., Rathore, R.S., 2014).

But, key elements of NWP 1987 remained unimplemented and NWP 1987 fell short of achieving its objectives due to lack of positive response from the State Governments inform Paranjpye, V. and Rathore, R.S. (2014).

Read more about it here

|

Events that led to the Water Policy 2002

(Table source: Gupta, M. and Biswas, R. (2021) Structuring of water policies in India: An overview, Nagarlok, Vol LIII, Issue 4, 42). Nagarlok is a quarterly open access journal. |

National Water Policy, 2002

The Second National Water Policy statement was released in the year 2002.

The preamble to the policy provides an understanding of the important principles on which the policy is

based and includes:-

- Commitment to Integrated Water Resources Management and Development.

- Importance to environment related concerns

- Importance to innovative techniques and strategies based on science and technology (Siddiqui, M.S., Date not specified)

The salient features of the National Water Policy 2002 can be found here

The details on the different sections of the policy and a comparison with the 1987 policy can be found here

NWP 2002 fell short of bringing about reforms to mitigate the problem of floods, bring more area under irrigation, increasing utilisation efficiency for irrigation and also increase food grain production (Paranjpye, V., Rathore, R.S., 2014).

It also fell short in preventing pollution of water bodies, making available potable water and sanitation facilities to the population in rural and urban areas, maintaining environmental flows of rivers, integrating different components of the water sector at the sub-basin or river-basin level (Paranjpye, V., Rathore, R.S., 2014).

However, 2002 policy strongly recommended the promulgation of a ‘Dam Safety Legislation’, amendment of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956 for time-bound resolution of disputes and legislation for preserving of existing water bodies by preventing encroachment and deterioration of water quality. But all these reforms remained unfulfilled (Paranjpye, V., Rathore, R.S., 2014).

Read more about it here

|

Events that led to the Water Policy 2012

(Table source: Gupta, M. and Biswas, R. (2021) Structuring of water policies in India: An overview, Nagarlok, Vol LIII, Issue 4, 42). Nagarlok is a quarterly open access journal. |

The National Water Policy, 2012

Under the National Water Policy, 2012, a number of recommendations were made for conservation, development and improved management of water resources in the country.

The salient features of the National Water Policy 2012 can be found here

The policy faced limitations in terms of delay in creating River Basin Agencies/Authorities/ Organisations, inadequate implementation of policy recommendations, intractable inter-state disputes and over-optimistic estimates regarding India’s annual water availability. It also did not consider ancient water cultures in India, the irrigation energy nexus, the changing patterns in water use for irrigation, application of IWRM principles and the issue of privatisation of water and water grabbing (Paranjpye, V., Rathore, R.S., 2014).

The ‘subsidiarity principle’ i.e. the devolution of planning and decision-making powers to the lowest appropriate level was also absent in the policy. It avoided listing of priorities and only mentioned different types of water uses. It also did not give adequate importance to the diversity in geographic conditions, agro-climatic zones, socio-economic disparities in the country etc inform Paranjpye, V. and Rathore, R.S. (2014).

What are the challenges to policy making in the country?

Gupta, M. and Biswas, R. (2021) state that a comparison of NWP 1987, NWP 2002, and NWP 2012 shows that the policies lack in the ‘Water Law’ component of the water institutions and thus have weak legal strength. Although they qualify well in the ‘Water Policy’ part, they seem to lose out on ‘Water Administration’.

Water policy in India is constantly evolving, but the Central and state water institutions continue to have inconsistent and overlapping policies hindering progress. Water policies in India are also found to face a number of barriers in cases such as implementing groundwater rights, metering tube wells, etc.

The formation of water policy involves various authorities functioning along different political boundaries between districts, regions, states, etc. and hydrogeological boundaries like basins, sub-basins, and catchments, etc. making implementation difficult due to lack of a common framework.

Lack of adequate and disaggregated data or availability of contradictory data by different water institutions and at the river basin management level makes planning, management extremely difficult. Coordination between different departments such as the Ministry of Water Resources, Rural Development, Agriculture and Urban Development, etc. at the Centre and states makes it even more exhausting. The economy is another challenge for effective water governance (Gupta, M. and Biswas, R., 2021).

In 2015, a committee of seven members (Mihir Shah Committee) was formed on the restructuring of the Central Water Commission (CWC) and Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) to form the National Water Commission (NWC).

The report proposed a paradigm shift in governance along twelve main areas. The report was criticised for being voiceless on challenges of allocation of water in different sectors, rules for allocation, enforcement, performance checks, etc. at the basin level. It was felt that the report fell short on reinventing institutional and economic reforms (Shah, M., 2018).

The details of the report can be accessed here

The new Karnataka State Water Policy

An important development in 2017 included the setting up of the Task group by the Karnataka Jnana Aayoga (KJA) to draft a new water policy for the state, which was led by Prof Mihir Shah, Shri S V Ranganath and Dr. Sharachchandra Lele. The Task Group submitted a comprehensive report to the Government of Karnataka, including a new draft Water Policy for the state and a detailed rationale to back up its recommendations. The draft report was submitted in 2019 and presented some very interesting insights related to the water law and water administration components missing in the earlier NWP 1987, 2002 and 2012.

It recommended a complete overhaul that included passing an overarching water framework law for water governance, a revamped groundwater act and irrigation act nested within a law for setting up water regulatory authorities at state, basin and sub-basin level, reshaping water-related agencies to increase citizen voice, transparency and accountability in the governance of the pollution board, the water boards, and city water management - as well as radical changes in the staffing and administrative structure of these agencies. This was to be coupled with a new mission for water data collection, analysis, research, dissemination and outreach that provided information at all levels for water governance and to the public to encourage efficient, sustainable and equitable management of water resources in the state.

The details of the report can be accessed here

Also read this interview with Dr Sharachandra Lele to know more about the important features of the Karnataka State Water Policy.

The future

In November 2019, the Ministry of Jal Shakti for the first time set up a committee of independent experts to draft the new National Water Policy (NWP). Over a period of one year, the committee has received 124 submissions by state and central governments, academics and practitioners. The NWP is based on the consensus that has emerged through these wide-ranging deliberations and focuses on:

- A shift away from a supply-centric approach involving dam construction and groundwater extraction, to managing demand and distribution of water.

- Diversifying public procurement operations to include nutri-cereals, pulses and oilseeds to encourage farmers to change their cropping patterns and save water.

- Reduce-Recycle-Reuse for integrated urban water supply and wastewater management, treatment of sewage and eco-restoration of urban river stretches through decentralised wastewater management.

- Non-potable uses of water such as flushing, fire protection, vehicle washing must mandatorily shift to treated wastewater.

- The NWP points to huge amounts of water stored in big dams, which are still not reaching farmers and explains how irrigated area can be expanded at very low cost by deploying pressurised closed conveyance pipelines, combined with Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems and pressurised micro-irrigation.

- Supply of water through “nature-based solutions” such as the rejuvenation of catchment areas through compensation for eco-system services.

- Blue-green infrastructure in the form of rain gardens and bio-swales, restoration of rivers with wet meadows, constructed wetlands for bio-remediation, urban parks, permeable pavements, green roofs etc are proposed for urban areas.

It is important that the policy is implemented by 2030 if India’s water woes are to be solved. (Gupta, M. and Biswas, R., 2021).

State Water Policies

Water is a state subject in India, and the state has the liberty to draw its strategies based on the functions required within their boundaries. Many states in India have their own water policies. These policies are based on the National Water Policy, and convert the National Water Policy into a strategy relevant to the state.

- Maharashtra State Water Policy 2019

- Gujarat State Water Policy 2015

- Rajasthan State Water Policy 2010

- Uttar Pradesh State Water Policy 2020

- Himachal Pradesh State Water Policy 2013

- Tamil Nadu State Water Policy, 1994

- Andhra Pradesh State Water Policy 2009

- Kerala State Water Policy 2008

- State Water Policy Karnataka, 2022

- Madhya Pradesh State Water Policy, 2003

- Water Policy Delhi, 2016

- Jammu and Kashmir State Water Policy and Plan 2017

- Assam State Water Policy, 2007

- Bihar State Water Policy, 2010

- Chhattisgarh State Water Policy, 2012

- Goa State Water Policy, 2021

- Haryana State Rural Water Policy, 2012

- Haryana State Urban Water Policy, 2012

- Jharkhand State Water Policy, 2011

- Kerala State Water Policy, 2008

- Manipur

- Meghalaya State Water Policy 2019

- Mizoram

- Nagaland Water Policy, 2016

- Odisha State Water Policy, 2007

- Punjab State Water Policy, 2008

- Sikkim

- Tripura

- Uttarakhand

- Uttar Pradesh State Water Policy

- West Bengal

References

- The World Bank (2023) How is India addressing its water needs? Accessed from the site: on 8th September 2023.

- NITI Aayog (2018) Composite Water Management Index: A tool for Water management. Accessed from the site on 8th September 2023.

- Rathee, R.K., Mishra, K.S. (2021) Water Policies in India: A critical review. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 14(47):3456-3466.

- Gupta, M. and Biswas, R. (2021) Structuring of water policies in India: An overview, Nagarlok, Vol LIII, Issue 4, 42).

- Cullet, P. and Gupta, J. (2009) Chapter 10. India: Evolution of Water Law and Policy. In: Joseph W. Dellapenna & Joyeeta Gupta (eds), The Evolution of the Law and Politics of Water, Dordrecht: Springer Academic Publishers, 2009, p. 159.

- Paranjpye, V. and Rathore, R.S. (2014) Position Paper on Understanding and Implementation of National Water Policy of India - 2012. India Water Partnership (IWP). Accessed from the site on 8th September 2023.

- Siddiqui, M.S., Date not specified) Water policies and legal framework in India. Accessed from the site on 8th September 2023.

- Mihir Shah (2018) Discussion Paper: Reforming India’s Water Governance to meet 21st Century Challenges. Accessed from the site on 8th September 2023.

/faqs/water-policies-india-past-and-present