The road to hell, they say, is paved with good intentions. A visit to almost any village or small town in India today will serve to confirm that statement. In an undoubtedly laudable attempt to keep the village clean, gram panchayats tend to dump waste in a convenient patch of land on the outskirts. That is, those few of them who actually think of the issue of solid waste management (SWM) at all. For most panchayats, sanitation begins and ends with defecation.

Counting toilets: The Panchayat heads are not to be blamed for this assumption. They are merely following the lead of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. The government's flagship programme, the 'Swachh Bharat Mission' focuses almost exclusively on the construction of toilets. There is a certain financial provision for solid waste management (between 7 to 20 lakhs for villages depending on population), but the monitoring and reports focus exclusively on the number of toilets built.

Piling up the waste: There is evidence however, that the results of this obsessive counting of toilets is more an indication of the government's 'infrastructure bias' than it is a gauge of the actual cleanliness of an area. Improperly disposed solid waste - which the Mission turns a blind eye to - has been linked to water logging, spread of disease vectors, wildlife deaths, air pollution, release of carcinogenic substances, and water pollution.

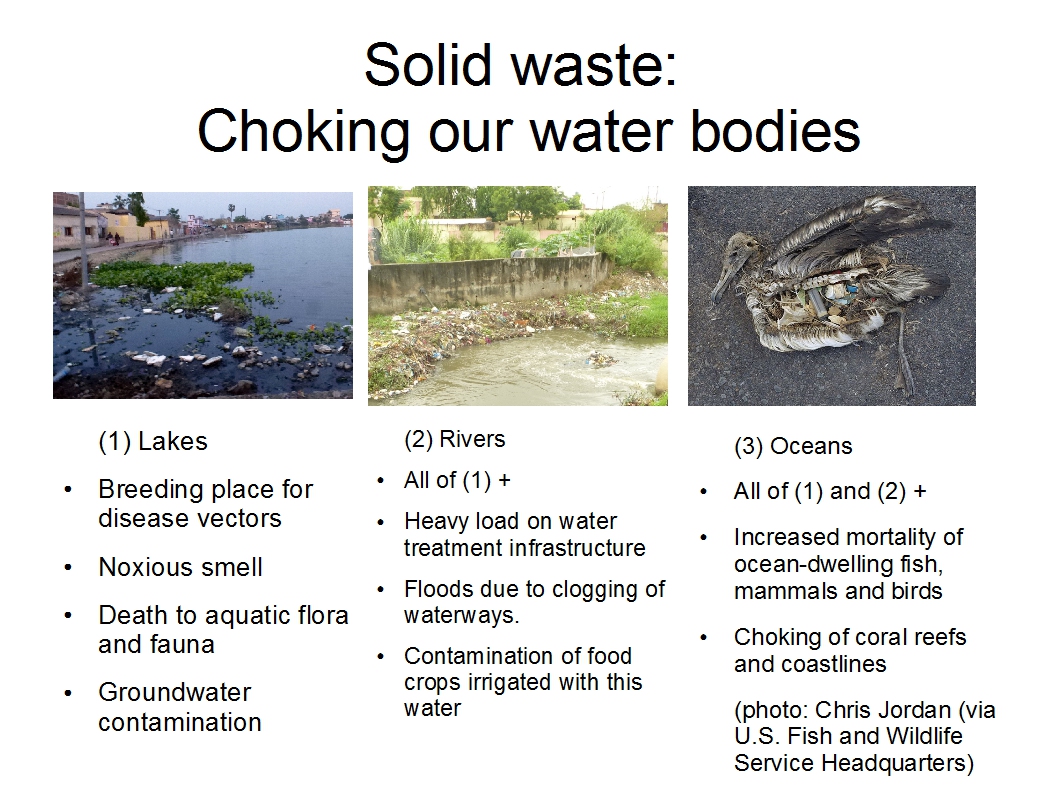

And floating it down: The impact of improperly disposed solid waste is most evident when it comes to the health of our water bodies. Dumping waste in low-lying areas converts wetlands into cesspools. These not only clog natural drainage, but also breed disease vectors like mosquitoes and leach toxins into the groundwater. Solid waste in our rivers, in addition to the above impacts also float down into the sea. Solid waste dumped in our oceans has led to the creation of five great garbage dumps in our oceans. It is nearly impossible to overstate the extent of solid waste in our oceans. Every beached pelagic creature now has plastic waste in its body. Simply put, solid waste is a health nightmare - a fact underscored by recent news of beached whales with car parts, plastic and other garbage in their bodies.

Goa seems to be the exception.

'SWM'-ing against the tide: The moment you cross the border from Maharashtra, a large sign on the highway informs you that now that you are in Goa, littering is no longer an option. Or words to that effect, I am paraphrasing here. It seems that Goans take this seriously. The elsewhere-ubiquitous piles of rubbish outside villages are missing here. Clearly, the formidable 'Rs.5,000 fine for littering' signs do have some effect.

But if not here, then where? Where does the Goan garbage go? Into the sea, like that of Mumbai?

Sorting the matter out: Some of it might be; no one's perfect after all. But an astonishing amount of garbage, both in rural and urban areas, gets sorted. It is then recycled or composted.

Metal, paper, glass and plastic bottles are easy. Selling these to the local 'Kabadiwallah' has been a part of frugal Indian culture for a very long time. Plastic bags are a trifle more difficult, but if cleaned and saved can be pelleted and recycled. Juice boxes need special treatment. Clinton Vaz,of V-recycle, is one of the few people who does accept them. These then get sent to a specialised plant to begin a new life as roofing sheets. The nightmare, says Espie Kandolkar of Green Goa Works, is used diapers and sanitary napkins. They encourage builders to set up incinerators for these. All organic waste gets composted and used by Goa's burgeoning population of urban gardeners.

Doing their bit: So who's 'they'? A variety of people are involved in this. Some municipalities, like Bicholim, have also mandated segregation of waste at source. Goa is home to several entrepreneurs who work in solid waste management (SWM). One of these is Green Goa Works, set up by the people behind the Goa Foundation as a 'non-profit company'. Espie Khandolkar explains, 'We carry out household level training in waste management. For this, we have created leaflets that households can follow like a recipe. However, we still do monitoring in restaurants, industries and some complexes.' Other organisations like Clinton Vaz' V-recycle also train their clients, who include Panchayats and then also offer a waste-collection service. Panchayats get funding of upto Rs.50,000 per annum for waste management. But they need to know what is to be done. There is a government vehicle that comes when called to collect waste, but requires it to be segregated.

Doing their bit: So who's 'they'? A variety of people are involved in this. Some municipalities, like Bicholim, have also mandated segregation of waste at source. Goa is home to several entrepreneurs who work in solid waste management (SWM). One of these is Green Goa Works, set up by the people behind the Goa Foundation as a 'non-profit company'. Espie Khandolkar explains, 'We carry out household level training in waste management. For this, we have created leaflets that households can follow like a recipe. However, we still do monitoring in restaurants, industries and some complexes.' Other organisations like Clinton Vaz' V-recycle also train their clients, who include Panchayats and then also offer a waste-collection service. Panchayats get funding of upto Rs.50,000 per annum for waste management. But they need to know what is to be done. There is a government vehicle that comes when called to collect waste, but requires it to be segregated.

Challenges: And here is where the difficulty comes in. Segregation of waste, except where it can be sold, is a foreign concept to many. According to Khandolkar, the attitude towards segregation before a collector picks up waste is 'he's a worker, he's being paid to do his job.' This is exacerbated with the popularity of garbage bags which encourage people to (in the words of the old advertisement) 'fill it, shut it, forget it'. Khandolkar says, 'We need to remember that waste workers are human too. For this, solid waste management (SWM) awareness needs to start in school. It should be a part of the curriculum at primary school.'

Yes, it should be. But till that happens, Goa is doing a fine job of managing it's garbage. Will the other states learn?

/articles/swm-ing-against-tide