Springs play an important role in the daily lives of thousands of communities in the hills and mountains of the Himalayas. However, in many places once reliable springs are drying up, presenting rural communities, and women in particular, with new challenges. In the Himalayan region, natural springs and their sustainable development are not given due importance at both policy and practical levels, even though they play a critical role in water security. To develop solutions to address changes in these traditional sources of water, there are large gaps in data and understanding that must first be filled. There is also a need to raise awareness among relevant policy and decision makers and to develop skills and share knowledge on this critical topic with field practitioners and community members.

The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), together with partners in the region, is working to research spring hydrogeology, promote awareness of the importance of groundwater recharge in the productivity of springs, and build capacities to protect and develop springshed across the Himalayas. In several of ICIMOD’s initiatives, a springshed management approach is being piloted in several transboundary areas, including the Koshi River basin and the Kailash Sacred Landscape.

An Initiative for Conservation and Development

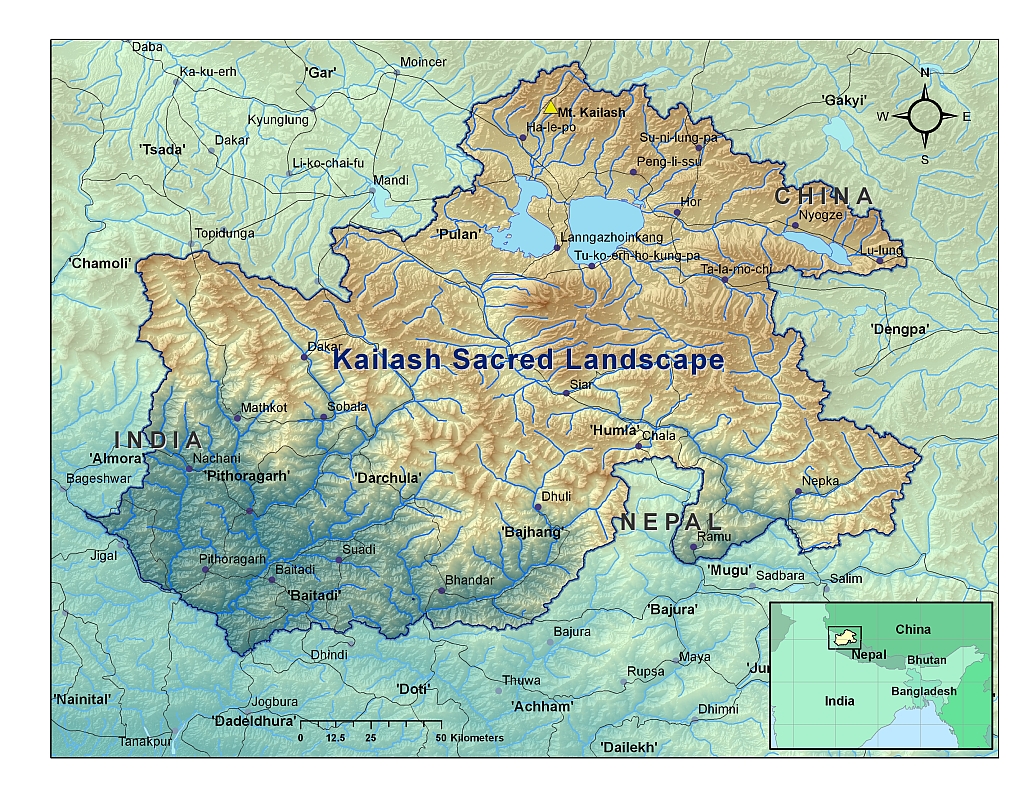

The Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation and Development Initiative is a transboundary programme facilitated by ICIMOD and endorsed by three governments -- China, India, and Nepal. These countries have defined the transboundary Kailash area as a single landscape for several reasons, including the ecological, cultural, and physiographic similarities across national borders. The headwaters of four major Asian rivers -- the Brahmaputra, Indus, Sutlej, and Karnali -- emerge from this region. Despite the landscapes expanse, it is ecologically fragile due to the impacts of both climatic and non-climatic factors.

The Kailash Sacred Landscape initiative was designed as a platform for the development of a shared conservation management strategy among the three countries. Although it emerged from its initial phase as a conservation programme, in 2013 the livelihoods component gained prominence within the initiative as it entered into a phase of implementation. That, along with the initiative’s cultural component, is all to do with communities. So now it is a conservation and development programme.

The reason for springs

When we started this initiative, water was not a primary focus. However, when we started conducting needs assessments in 2013, many of the needs people expressed centered on water. With the high dependence of people in the Kailash landscape on springs, particularly communities in the Indian and Nepali parts of the landscape, we were compelled to put more effort into understanding spring hydrogeology, promoting spring conservation, and answering the question of why Himalayan springs are drying up. This is not only an issue in Kashmir, Sikkim, and Uttarakhand. Throughout the Himalayas there are scientific evidence and local reports of springs dying. This is a regional issue, and as an institution, ICIMOD has experience and a mandate to work on regional issues.

In this sacred landscape, water is intrinsically linked to culture. A ‘dhara’ or ‘naula’ is also a god or goddess. During field research, we found that if a spring dries up or is contaminated, it often viewed as a risk to traditional beliefs and cultures. These kinds of thoughts resonate with many people throughout the region. Cultural and environmental conservation can be intertwined to strengthen both. We are still exploring this, but we’ve found that water is a key entry point into landscape conservation.

Opportunities for research

There is a gap in data on the dependence of mountain populations on springs. An initial assessment by ACWADAM in Meghalaya, Sikkim, and Uttarakhand found that 80-90% of the population depends on springs. We believe that this is likely true across the mid-hills in the Himalayan region, but there is no accurate data to confirm this. ICIMOD sees this as an opportunity to contribute to filling data gaps, including through embedding a hydrogeological-based springshed approach in integrated watershed management strategies, developing a regional map on springs, and preparing simple ‘how to notes’ on techniques that can be used to support groundwater recharge and improve groundwater quality. Through the Kailash initiative, we have started mapping springs, including hydrogeology, and building the capacity of locals on managing groundwater and sanitation issues in Pithoragarh District in India and Darchula District in Nepal. This activity is being undertaken together with ACWADAM, who is facilitating applied research in the Indian and Nepali parts of the Kailash landscape. We are also building capacities of our partners implementing the programme in both these countries.

Opportunities for policy change

There is a need for policy change related to groundwater conservation and use in the Himalayan context. In Nepal there is not an enabling environment that focuses on groundwater policy. Although there is a Groundwater Resources Development Board, but there is no scientific evidence to base advocacy or policy on. Because we are headquartered in Kathmandu, and due to our close working linkages with various ministries and line agencies in Nepal, ICIMOD is in a good position to engage with policy makers on such a timely issue like springs. In districts hard hit by the recent earthquake like Sindhupalchowk and Kavre, people have observed changes in spring discharge, with some drying up, and others with increased flow. New springs have also emerged in places where there weren't any before. Because of this, the whole aspect of geology has come into focus, and it is timely to work with the Groundwater Resources Development Board of Nepal to assess the current policy under this new context.

I’m interested in looking at groundwater as a common pool resource. This is easy for things that can be seen – we can see forests and land and clearly say "this defined area is community property that everyone has access to". But we can't see groundwater stored in springs and aquifers, so this can be quite challenging and requires a change in the current mindset. We are shifting the mindset from groundwater as a 'source' to a 'resource'.

Lithodiversity

When we look at forests, land, and farms, there are obvious links to biodiversity. We see it at the surface level – different types of trees and animal species, etc. What people, including scientists, don't yet recognize is that what is underneath the Earth’s surface is also an ecosystem. The term that we should use now is lithodiversity. The lithosphere is an ecosystem in itself. If a spring dries up, there are direct consequences on the larger ecosystem it is a part of: the soil will go dry, the nutrients in the soil will reduce, and forests will suffer. If a wetland that supports a unique bird dries up, then what happens to the ecosystem? There is no holistic concept of the ecosystem that doesn’t consider hydrogeology. Biodiversity in conjunction with lithodiversity is something we need to look into in the future, and our efforts to study springs under this initiative is providing us with a very good understanding of how these two are entwined.

Nawraj Pradhan is the Associate Coordinator for the Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation and Development Initiative at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

/articles/groundwater-its-not-source-its-resource