Dams have often been regarded as man’s response to nature’s vagaries, to mitigate flood and drought by containing water and releasing it as per demand and supply. Lately, dams are seen more as hydropower generators with flood mitigation, irrigation and drinking water supply only being additional benefits. This can be because of the increased acceptance that dams and canals, as awe inspiring as their structures might be, fail to deliver water to more than half of their commands. However, data and experience tell us that even the hydropower generation is also falling way below the promised numbers.

History and extent of dams in India

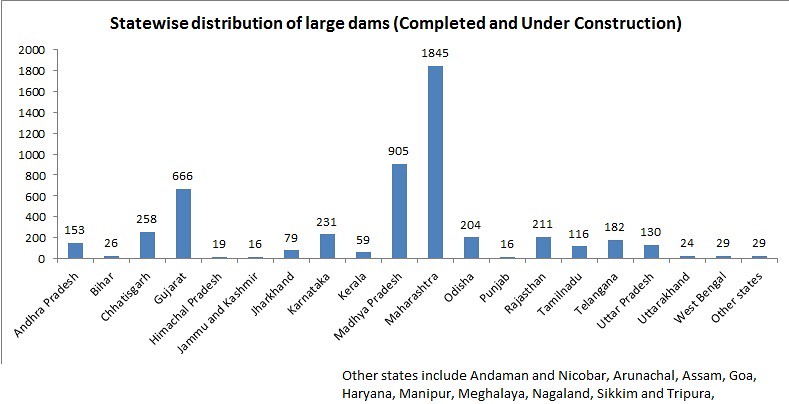

India’s first dam is the Kallanai built on the Cauvery river by King Karikalan of the Chola dynasty around 2,000 years ago. The dam, which is still functional and irrigates millions of acres, spans 329 m in length and 20 m in width. However, it was only post-independence that India’s love for big dams became more intense with the commissioning of a slew of projects including the Hirakud (1957), Gandhisagar (1960), Bhakra-Nangal (1963) and Nagarjuna Sagar (1967). Since then, the country has been continuously working on reining in its rivers for want of power, irrigation and domestic and industrial water supply needs. Almost half of the large dams in the country were built in the two decades of 1970-90. Maharashtra has the maximum number of large dams in the country (1845) followed by Madhya Pradesh (905) and Gujarat (666).

Map of major dams in India

A multi-purpose dam project includes one or more dams, infrastructure for generation of hydropower, infrastructure for housing of workers and for offices, a distribution network of canals and pipe systems, and access roads. All these have their individual and cumulative impacts on the river and the surrounding environment. Here also lies an opportunity to minimise the 'collateral damage' caused by dam projects by minimising the footprint of these adjuncts.

Dams as power generators

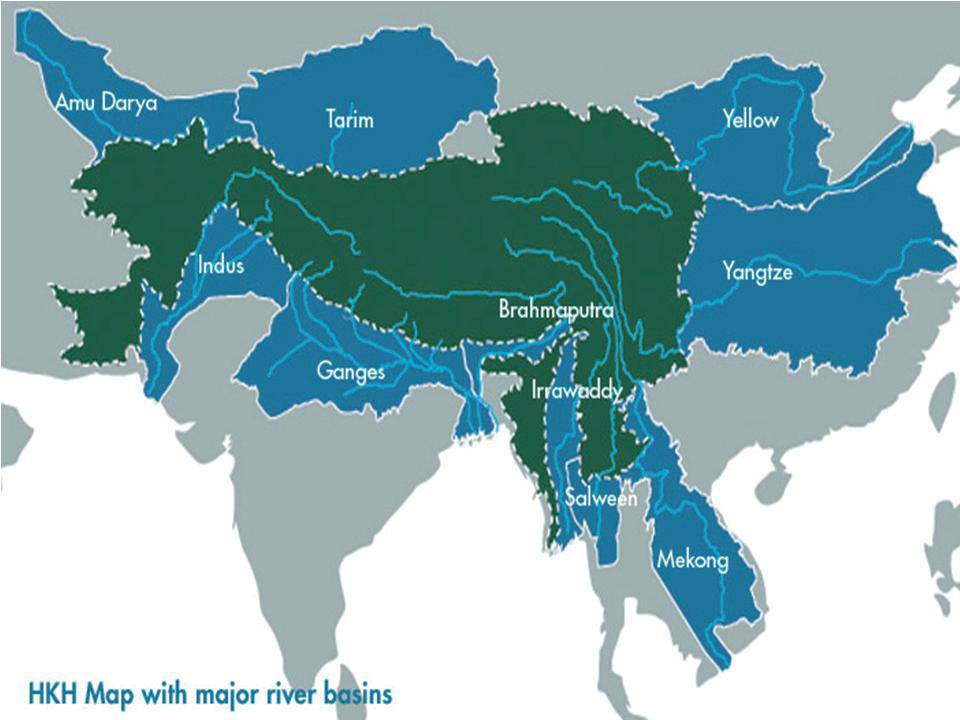

Hydropower is often billed as a renewable, economic and non-polluting source of energy and hence there is an increased emphasis on building dams especially in the hydrologically-rich but geologically-fragile Himalayan states. An assessment study put the hydroelectric power potential of the country at about 84,000 MW with maximum schemes envisaged on Brahmaputra basin (226) followed by Indus basin (190) and Ganga basin (142).

Possibility of revenue generation through sale of power units to other states and private players remains the main draw for state governments to invite project developers. However, reports suggest that poor financial conditions of discoms make it a poor proposition. Average generation per MW of hydro capacity in India in 2014-15 was over 20 per cent less than that in 1993-94.

Dams and canals for irrigation

Canal system of irrigation had been prevalent in India for centuries but it was the Ganga Canal that laid the foundation for large scale diversion of water to farms.

Though the work was undertaken under the leadership of British Colonel Proby Cautley, it was the traditional acumen of local villagers that made the vast network possible. The canal was commissioned in 1855 irrigating around 5,000 villages. Today, the system irrigates nearly 9,000 km² of agricultural land in 10 districts of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

Though the work was undertaken under the leadership of British Colonel Proby Cautley, it was the traditional acumen of local villagers that made the vast network possible. The canal was commissioned in 1855 irrigating around 5,000 villages. Today, the system irrigates nearly 9,000 km² of agricultural land in 10 districts of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

The start of the Green Revolution in the mid 1960s put the spotlight on canal irrigation as the new hybrid crop varieties bred on heavy dose of chemical fertilizers and pesticides demanded assured irrigation. However, the increased investment and network expansion dealt little benefits. The World Commission on Dams in its year 2000 report found that the contribution of large dams to increased food grains production in India was less than 10 percent.

Loss in seepage, huge demand-supply gap, diversions under political pressures and comparatively easier and local availability of groundwater through pervasive use of borewells are the reasons for decline in efficiency trend.

Between 1996-97 and 2002-03, the area under canal irrigation declined by 2.4 million ha (13.8 per cent), the area under tank irrigation fell by 1.4 million ha (42.4 per cent), and the area irrigated by all other sources declined by 1 million ha (28 per cent). The only irrigation source that increased its share was groundwater wells, by 2.8 million ha (more than 9 per cent).

A study of 210 major and medium irrigation projects by SANDRP used the data supplied by the Ministry of Agriculture to show that after investing Rs 130,000 crore, these delivered 2.4 million ha less irrigation during 1990-1 to 2006-7. This means, the governments have to invest twice as fast in canal irrigation projects every year just to keep their command areas from shrinking

The study said that around Rs 1,00,000 crore was wasted in the name of improving irrigation. Feasibility studies were fudged in the case of most of the projects with huge investments, over-optimistic predictions were made and very little money was earmarked for basic maintenance such as desiltation. In some cases, political interests ensured that water was diverted to unviable areas at the cost of needier regions.

Dams and flood control

The efficiency of dams to withhold floods has always been put to question. Critics have also termed dams as harbinger of floods claiming that the essential scientific assessment for consistent release of water to avoid build up is rarely done.

Absence of a standard operating procedure for releasing water from the dam gates was evident in 2014 when 24 students picnicking in a river were swept away due to sudden release of water from Larji dam in Himachal Pradesh.

Similarly, area downstream of Hirakud dam in Odisha has witnessed 14 floods in recent past with nine caused by sudden release of water from the dam. A major reason is that the dam has not changed its flood control strategy for 23 years while the rainfall pattern has undergone major changes in local areas. Lack of a coordination mechanism between neighbouring states about water flow also leads to emergency situations like one in 2011 when sudden release of water flow from upstream dams in Chhattisgarh led to breaching of danger mark in Hirakud.

In Gujarat, sudden release of large quantities of water from Ukai dam led to the biggest flood of 34 years in Tapi river submerging over 80 per cent of Surat, killing 150 persons and stranding over 20 lakh. Similar examples have been reported from other states.

Problem with 'training rivers'

Dams cause a disruption in the flow of a river by transforming it into a series of pools separated by dry stretches. The environmental impacts can be felt on the landscape, water resources, forest cover, and biodiversity. The Himalayas are almost equally distributed between zones 4 and 5. While a series of dams are being constructed in a seismically vulnerable and ecologically fragile zone, not only is optimisation of the planned development not considered, but the cumulative effects of the dams also are not considered. On a local level, blasting increases the possibility of landslides, and causes air and noise pollution. Quarrying on hill slopes and in the riverbed causes pollution and destabilisation of the slopes.

The large scale construction that is an inescapable part of hydropower development leads to deforestation. It has been observed that construction leads to the inadvertent loss of much more forest than has been accounted for. The presence of a dam on a river also impacts the ecosystem by bringing about a drastic change in the species composition. Invasive species tend to appear and flourish while suppressing endemic species and even causing some to become extinct.

An affidavit filed by Ministry of Environment and Forest in the Supreme Court admitted the role of hydropower projects in Uttrakhand disaster in 2013. It said that “the maximum damage sites in the disaster affected areas (were) located either upstream or immediately downstream” from hydropower projects.

According to a paper by the United Nations Environment Programme, dams and their associated reservoirs permanently impact on freshwater biodiversity by several processes. Climate change has also been linked with dams. Studies show that large dams cause anoxic decomposition which leads to the formation of methane gas. This ‘greenhouse gas’ produced by dams may contribute to global warming to an appreciable extent. According to a study, dams contribute about 24 per cent of the total methane emissions in the world. Of these emissions, India contributes slightly under 28 per cent.

Submergence and displacement

Though the benefits of a dam are often exaggerated, the estimates related to land submergence and possible displacement of people are invariably kept low to paint a positive picture.

From Hirakud to Bhakra Nangal to Tehri and many more, scores of affected families were not rehabilitated at all. Those rehabilitated also complained about lack of livelihood opportunities and poor living conditions. Narmada Valley project, around which a big people's movement was built, remains the most controversial irrigation and hydropower plan. Envisaging around 30 irrigation and hydroelectric multipurpose dams, the project's environmental and social costs vis-a-vis the benefits have been cause of much debate and litigations. Sardar Sarovar dam, the largest structure on Narmada river, is believed to have displaced over 3 lakh families and is expected to displace additional 2.5 lakh families if its height is further increased by recently-approved 17 metre.

The World Commission on Dams in its report says: “While dams have delivered many benefits and made a significant contribution to human development, in too many cases the price paid to secure those benefits, especially in social and environmental terms, has been too high and, more importantly, could have been avoided.”

Political issues around dams

Shortage of water is increasingly being felt resulting in conflicts across the world. For the same reason India is facing disputes both within and outside its boundaries. While Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan are fighting over water sharing from Bhakra Nangal, Kerala and Tamil Nadu went to court on diversion of water from Mullaperiyar dam.

On the other hand, Pakistan claimed that design of Baglihar project in Jammu and Kashmir violated the Indus Water Treaty whereas India is wary of China's plan to tame Brahmaputra waters through a series of dams. Similar are the concerns of Bangladesh which lies further downstream over India's attempt to build dams.

Way forward

It is evident that instead of focusing on building new dams, we need to attend to underperformance of existing projects. Decentralised solar, wind energy and small hydroelectricity projects with local communities as their managers as well as consumers can offer sustainable alternatives to big dams. This will not only mitigate ecological and social impacts of power generation but also reduce cost of power generation and distribution.

For irrigation purposes, revival of traditional community-managed networks like kuhls of Himachal Pradesh, phad irrigation of Maharashtra and recharging of underground aquifers through rainwater

The World Commission on Dams lists seven steps as a remedy to issues arising from dams. These include gaining wide public acceptance, exploration of alternatives to dams, optimal usage of existing structures, protection and restoration of ecosystems at river basin level, recognising entitlements of the affected people, compliance with applicable regulations and regional co-operation on trans-boundary rivers.

A few of the western countries, having realised the futility of large dams, are trying to help rivers reclaim their territory. Dams that no longer serve a useful purpose, are too expensive to maintain safely, or have harmful impacts are facing the axe especially in United States where the rate of decommissioning of large dams has overtaken the rate of construction since 1998.

The provision of adequate environmental flow releases from dams is an important means of achieving a compromise between overt exploitation of our rivers and a non-practical cessation of all use. Attempts have been made towards the assessment of these flows for the Ganga, and an ongoing project aims to achieve implementation of these flows in the Ramganga. The successful process of e-flows in India may indicate that it is going to be mainstreamed into water resource management policy.

/topics/large-dams-barrages-reservoirs-and-canals